MDOT’s Michigan Avenue Plan Is A Game-Changer. Will It Happen?

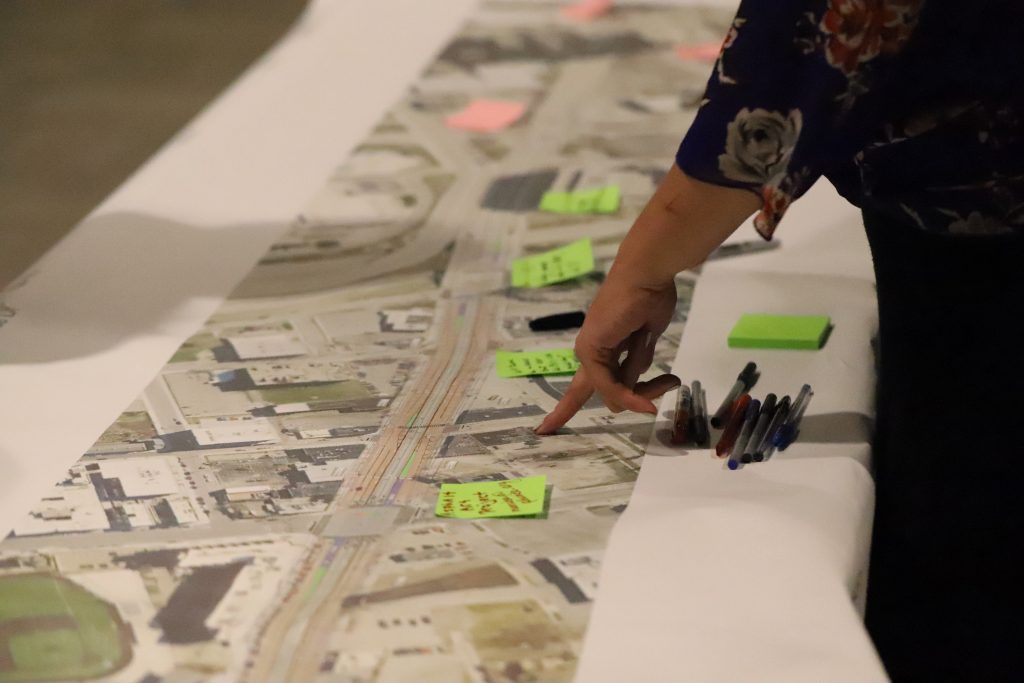

Living in a city where infrastructure ranges from broken (the lights on my local pedestrian bridge), to crumbling (alleys), to virtually nonexistent (bus service), it’s easy to get excited about announcements about Cool New Projects. Last night, I attended a public meeting hosted by MDOT at the IBEW in Corktown to talk about the state road agency’s plans for Michigan Avenue, everybody’s favorite baseline road that connects downtown Detroit to Dearborn via Corktown and Southwest Detroit. I am thoroughly optimistic about this project, with a few major caveats. Those caveats? MDOT and its partner Electreon. But the project itself? Very cool.

Michigan Avenue has been a focus for the city since the Michigan Central project evolved. Let’s recall that Ford once actually tried to build a subway along MIchigan Avenue to connect downtown Detroit to its factories in Dearborn. This project didn’t go anywhere, but they did, in the process, demolish all of the buildings on the south side of Michigan Avenue to widen the thoroughfare in the 1930s, which is why the street is so wide and why there are fewer historic buildings on the south side of the street. Fast forward to the modern day, and with the development of the Michigan Central project, we see that what Ford wants, Ford gets. An autonomous vehicle lane? Sure. Can we pair it with a bus-only lane? Apparently, yes!

Sidebar: Can A Wireless Charging Roadway Work?

I am skeptical of the self-charging roadway feature, which to me (as someone who has studied this stuff extensively) amounts to vaporware. This actually deserves its own article, which I wrote. But, as TRU’s Megan Owens pointed out, if it gets us the dedicated bus lane, why not support a self-charging roadway? Point taken.

However, I was curious to unpack why MDOT deemed it acceptable to narrow MIchigan Avenue, a street with an extraordinarily wide right-of-way, into just one travel lane in each direction plus the dedicated transitway (which, as Megan reminded me, is likely to remain a dedicated transitway until they figure out the self-charging car technology that currently doesn’t exist). I pointed out to the presiding road engineer that, in the I-375 redesign proceedings, MDOT had “listened” to everyone’s suggestions of making a narrower street to replace the 6-lane freeway and then had determined that we still needed a 6-7-lane boulevard.

The road engineer informed me that “this is different,” because I-375 handled a lot more traffic than Michigan Avenue. This claim we rated as “true, but misleading.” According to MDOT’s own post-COVID traffic numbers (2022 AADT), the section of I-375 south. of the I-75/Gratiot interchange had 40,351 vehicles. This includes northbound and southbound traffic. Northbound traffic is usually traveling from Jefferson, which includes downtown commuters leaving the city during evening rush hour, and vice versa in the morning. More than 10% of these cars, though, were going to the casino (4,669 vehicles per day). Ensuring a direct offramp connection for that lowers this to 35,682, which is 3.5x the traffic of the section of Michigan Avenue in question (9,440 vehicles per day).

A six-lane freeway can handle over 100,000 cars per day, while a four-lane street with left turn lanes can still handle 31,000 cars per day. Never mind that replacing I-375 with a surface-level boulevard would invariably reduce the traffic on it, because people are eager to speed home to the suburbs, and would likely consider alternatives, like the Lodge onramp, which is accessible via Jefferson westbound.

That means that MDOT, without providing any credible transportation alternatives, is saying that the only way to rebuild I-375 is to do it with six or seven lanes. Because there’s no universe in which the agency can imagine less traffic. Recall how the road agency’s representatives balked at the idea of VMT reduction targets. Michigan Avenue with only two travel lanes, meanwhile, is well-suited to accept far more traffic than it had in 2022. These two streets are very different, but the projects are worth comparing because they show how engineers are making decisions based on box-checking. “We see that we used to have [x] numbers, which means that we can only plan on over-engineering the capacity of the new road, instead of imagining alternatives.”

(These are interactions that make me feel like I’m not a professional city planner but rather a crazy person).

Also, does MDOT not believe in the principle of induced demand? Induced demand refers to the idea that in general, adding more road adds more traffic. It’s a question of driver perception. Drivers who see more road are more likely to drive. It’s a matter of visual cues as well as perception. Drivers who see more lane width, similarly, believe they can drive faster, and this is why best practices for safe street design include narrowing lanes to normal widths. Cities often refuse to narrow lanes under the principles that large trucks can’t navigate in narrow lanes. This isn’t really true– most fire trucks actually fit in a parking space from a width standpoint. The problem is that they execute very wide turns. There are ways around this, like designing intersections that can handle wider turns, even if the lanes remain narrow. One attendee last night remarked to me about how hard it was for Melanie Piana to get MDOT to get on board with a longtime plan for a road diet on Woodward in Ferndale. The agency is stereotyped as being difficult to work with on projects that impede the supremacy of the motorcar. Their excuse is usually that “well, that’s what hte legislature allows us to do,” which is at odds with the fact that they employ engineers who can only imagine one solution, and that solution is Cars.

But Michigan Avenue may be different. Will it happen? Given my experience with MDOT, I am doubtful. This project is supposedly set to begin in 2025. By that time, it’s possible that Electreon may have improved its technology– or figured out how it’s going to get adopted, perhaps. It’s also possible that Michigan Democrats will by that time be a bit more attuned to urban, rather than suburban, issues of infrastructure, street safety, and car dependency. Here’s to hoping.