Google Maps Needs To Do A Better Job Showing Pedestrian Infrastructure.

I’m in DC a bunch of the time these days in my decreasingly-new role with the Potomac Electric Power Company. We’re working to decarbonize the power grid. That’s a neat thing. Also neat is spending time in a city that I had as a reference point as a young’un, but now am, well, more or less living in part-time. My current digs are a quick Metro trip from the office, but it’s a weird series of paths to get from the house to the train, so I got to thinking about how Google Maps inadvertently promotes car culture based on the primacy– and sheer size- of automotive infrastructure. We’re looking at Rhode Island Avenue in Northeast Washington, DC.

Trail Meets Bridge Meets Road

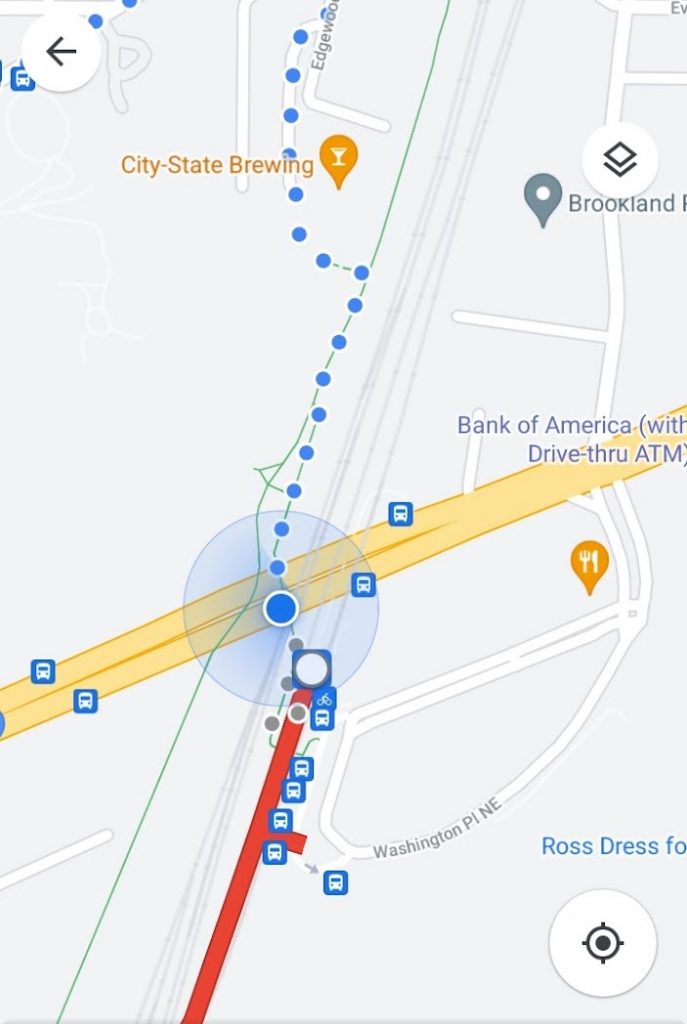

In the above example, I’m crossing from the Rhode Island red line Metro stop to the Metropolitan Branch trail. If you’ve made the trip, it’s easy. If you haven’t, as I hadn’t until yesterday evening, it’s a bit confusing to see the bright yellow, dominant lines of Rhode Island Avenue, even when that street is effectively buried beneath the two more relevant “real-life” layers of urban fabric including the trail and the pedestrian bridge. There’s no reason why, especially if I’m using pedestrian directions as opposed to driving directions, the map can’t redraw the pedestrian paths bigger. I guess that’s the point of the dotted line. But that doesn’t actually tell me anything about the route itself– it still subjugates the nonmotorized infrastructure, even though I’m not using the motorized infrastructure.

It may seem like nitpicking, but as we face the twofer of an epidemic of pedestrian fatalities and the threat of climate change, we should really be figuring out more ways to promote nonmotorized infrastructure.

But isn’t Rhode Island Avenue US Route 1?

Sure is! And what of it? No, seriously, I get that there is some value in labeling major trunkline routes, or major whatever transportation routes. After all, this exists already for most ways of getting around. Truckers, for example, have maps that give them the ability to see where they can and can’t drive a gigantic vehicle based on the clearance heights of things like bridges. Cars can and should stick to major routes instead of tearing up neighborhoods to save 45 seconds on a trip, like Waze tells them to.

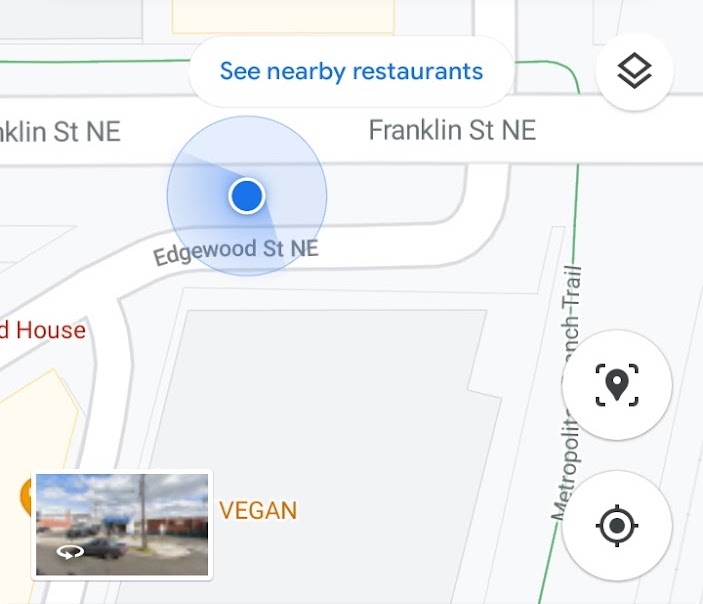

But when you’re figuring out routes as a pedestrian, why should the major routes for cars be important beyond, say, the location of crosswalks and signals? In the example below, we’ve crossed the Met Branch trail and are trying to figure out how to get up to Franklin Street. There is this weird little sidewalk. It isn’t shown on the map as a route, which means either Google Maps screwed up, or it’s private property. I did not exactly get chased by wild dogs crossing it, so it’s probably safe to assume that it’s okay to use this route.

What Google Could Do.

There are some basic improvements that Google Maps can make to improve legibility of maps for nonmotorized infrastructure. The company is apparently already working on some of these things, and I’ve already seen a few of them in action. My ideas include the accessibility of crosswalks and corners for differently-abled people. Another idea would be indicating marked crosswalks, locations of elevators, safe crossing routes for major roads, or showing things like stairs versus ramps. If you’re in a wheelchair, a ramp is often doable in a way that stairs absolutely are not.

The one nice thing about These Silicon Valley Companies is that, for all of their terrible qualities, they do tend to iteratively improve things. Google Maps is an impressively dynamic platform, and one I appreciate even more after being forced to us the horrendous map thing that is the default in Microsoft Edge Slash Bing. I am even imagining some sort of participatory feature where users can draw routes or annotate existing ones, and the company could potentially use this input to augment AI-developed interpretations of things like crosswalks or the locations of stairs or ramps. After all, Google Maps allows user modifications to things like business listings. And Waze encourages users to report things like accidents (probably a good idea) or speed traps (boo).