The Billion Dollar Hot-And-Ready: Touring Detroit’s Little Caesars Arena

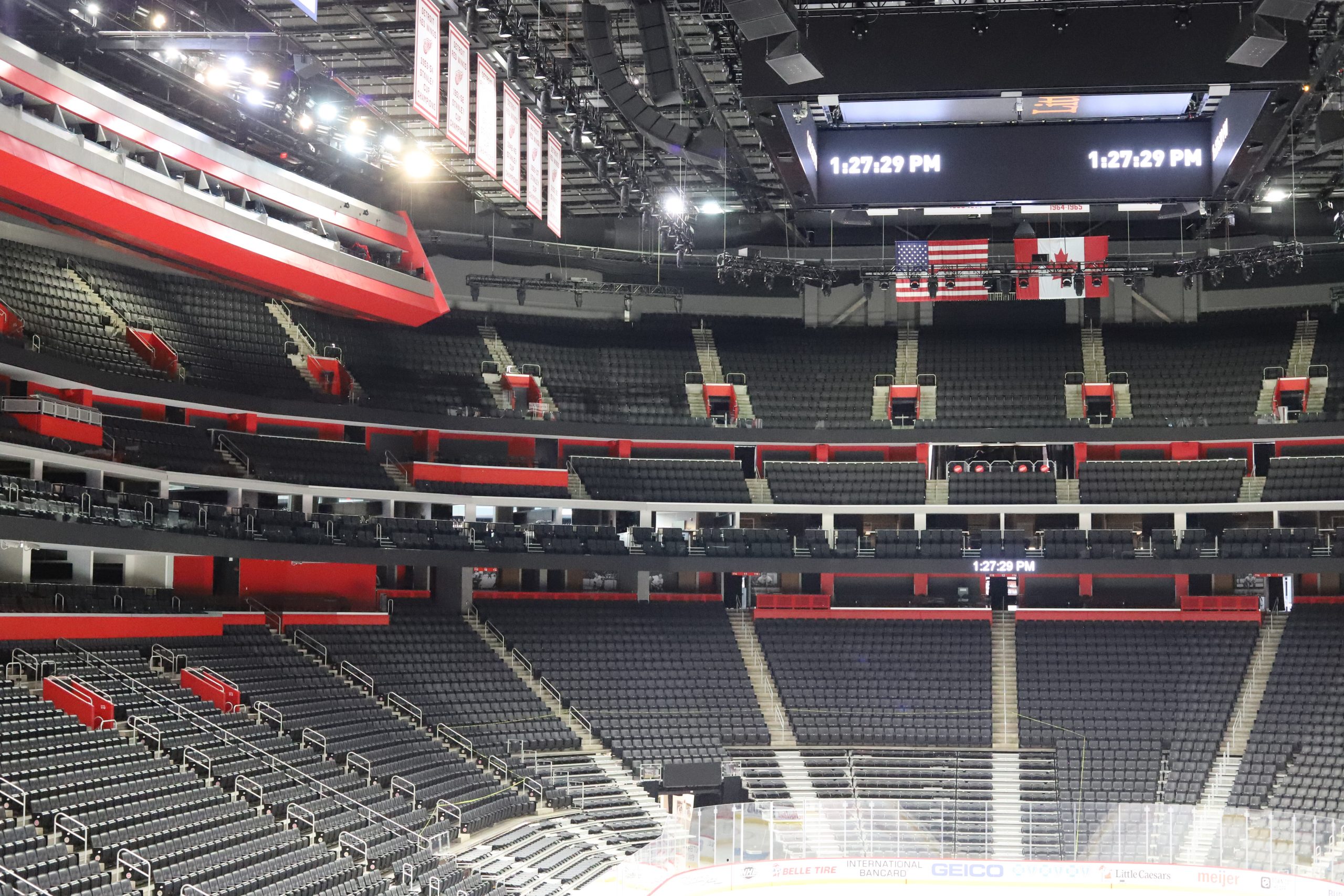

On Tuesday, I had the opportunity to tour the Little Caesars Arena, the new home to the Detroit Red Wings and the Detroit Pistons, with Detroit’s US Green Building Council chapter. I had taken a hiatus from our local USGBC chapter for a couple of years to focus on other projects, but I didn’t want to miss a tour of Detroit’s largest single development project in recent history.

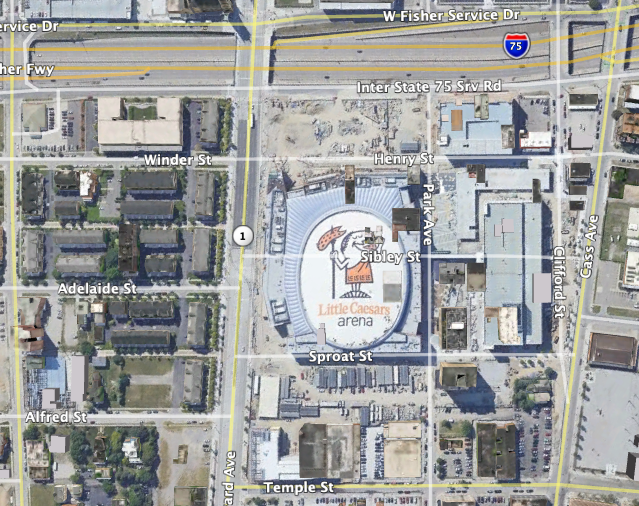

The Arena is located at 2645 Woodward Ave. in Detroit. Its opening in 2017 marked the first time in more than a generation that all four sportsball teams call the city of Detroit home. The Detroit Pistons played at the Palace of Auburn Hills after a stint in the Pontiac Superdome after leaving then Cobo Hall in the City of Detroit. The Detroit Lions, who hold the dubious honor of having never participated in any Super Bowl and who last won a championship shortly before the launch of Sputnik, played at the Silverdome after playing for years at Navin Field (a.k.a. Tiger Stadium or Briggs Stadium). The storied Red Wings have always played in the city of Detroit for the entirety of their nearly hundred-year history, as have the, ahem, less-storied Tigers.

The LCA has a far stronger urban context, at least on the Woodward side, than its southern neighbor of Comerica Park, which is surrounded by– you guessed it- parking lots on the Woodward side. Expansive pedestrian plazas ring the massive structure, whose footprint alone is a full eleven acres. There is direct connectivity to the Woodward transit corridor including Rapson’s Folly, a.k.a. the QLINE. There’s also a pretty stable mix of uses in the complex including offices occupied by the likes of Google and Kid Rock’s departing restaurant. The Mike Ilitch School of Business, where, one imagines, you can get a degree in pizza management and what Tom Perkins has called dereliction by design, gleams on Woodward Avenue just north of the LCA.

Inside, an interior, streetlike concourse separates the arena proper from the exterior, street-facing buildings, which include the office spaces and restaurants. I’m ever the fan of natural light inside large buildings. A clever roofing membrane involves a web of inflatable, transparent sort of pillows that form an air barrier between the conditioned interior and the exterior. Made out of a Teflonesque material (PFAS, anyone?), the membrane is designed to ensure that a failure of a single unit is not catastrophic to the rest of the structure.

URBAN CONTEXT

At a construction cost of nearly a billion 2019 dollars, the LCA also used a massive, controversial public subsidy package that cost taxpayers the better part of half a billion dollars. The first portion of this expansive financing package was approved by city council just after the city declared bankruptcy.

An HBO documentary examined the unfulfilled promises by Olympia Development Michigan (ODM), the real estate firm of the Ilitch family that owns not only the Arena but also Motor City Casino, the Detroit Tigers, and more. Part of the terms of the public financing package were that Olympia would develop nearby real estate. This hasn’t happened, though plenty of demolition has occurred to build parking lots– which apparently aren’t even compliant with city code requirements for surface parking.

A popular Facebook page, Terrible Ilitches, has chronicled the snail’s pace of surrounding development in Midtown at the hands of Olympia. The page, whose author remains anonymous, highlights examples of successful development, often with the snarky adage that a specific project’s very completion is how you know it isn’t an Ilitch property, implying that the Ilitch clan doesn’t execute on their promises. (Side note: I’ve been trying to get material out of the city’s media team on this subject for months and they have declined multiple requests for comment. Various FOIA requests have meanwhile gone unanswered– or have turned up dubious results.)

I asked about this on the tour after one of the docents mentioned the plethora of unfair, bad press that the project gets. Why, if such an ostensible commitment to sustainability, such a commitment to hardscaped surface parking lots? A representative of ODM said that there is “no transit” in Detroit and that the adjacent QLINE cannot adequately serve the Arena. This second part is true, but the first part is utterly false, given the numerous bus routes that serve the Arena including the high-frequency Woodward bus and the FAST buses.

Meanwhile, a representative from Barton Malow was eager to extol the virtues of the LCA. The Joe Louis Arena was built out of cheap materials and wasn’t made to last, he said of the riverfront arena, whose steel and concrete shell has been in the process of gradual demolition for several months. The LCA, on the other hand, is built to last for 50 or 100 years, he says.

“I can tell you that when I first started coming down here, all of these were abandoned buildings and vacant lots–” he began.

“–which,” I cut in, “had been owned by the Ilitches for decades.” As part of a plot to basically hold the city hostage, saying “you have to give us all of this money or we will continue to sit on these derelict properties. Or we’ll move the Red Wings to the ‘burbs.”

I’m told that this is “political” and that I’m not supposed to ask these questions. Not really sure what else journalism is about.

THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING STADIUM LIFESPAN

Barton Malow man’s comment about the LCA being built to last a century, of course, at odds with ample data points that indicate a downward curve of stadium lifespans over time. Corporate-sponsored sportsball teams demand fancier, newer, and, of course, taxpayer-subsidized stadiums after only a few decades.

Neil deMause and Joanna Cagan wrote a whole book about this. Field of Schemes: How the Great Stadium Swindle Turns Public Money Into Private Profit (2008) covers a strong trend of staggering budget overruns and a tap of endless public subsidy to build economic development projects that don’t pan out too well for the taxpayer. The decreasing lifespan of stadiums has also been a subject of discussion in recent years as taxpayers are expected to shoulder an ever-larger share of the growing costs.

Even if a building is built to last a century, it probably won’t last more than twenty years before the team (and its billionaire owner, likely) begins clamoring for a new stadium.

Consider these, with cost estimates in 2019 dollars and per-year construction cost:

- Edward Jones Dome in St. Louis (1995-2015). $470 million, $23.5m per year.

- Turner Field in Atlanta (1997-2016). $341 million, $17.9m per year.

- Pontiac Silverdome (1975-2002). $321m, $11.9m per year.

- Houston Astrodome (1967-1999). $284m, $8.88m per year.

- Detroit’s Joe Louis Arena (1979-2017). $201 million, $7.2m per year.

- Palace of Auburn Hills (1988-2017). $195 million, $6.72m per year.

Compare that with the original Olympia Stadium (1927-1987, $36.8 million, or $736,000 per year), after which the eponymous, Detroit-based parking management– I mean, real estate development- company is named. Sure, it didn’t have a seventeen-acre Daktronic screen. But it was a neat building. And we’re not talking about a profitable business venture. We’re talking about a publicly subsidized corporate project. Of course, most Detroiters can’t even afford Red Wings tickets, let alone $12 beers.

A critic of my characterization here might note that many stadia are reused, rather than demolished. This would be a bit misleading because virtually all stadiums are purpose-built for a specific team or teams. It is not going to be as profitable if used as, say, a minor league hockey stadium or practice facility than it would be as an NFL, NBA, NHL, or MLB franchise.

EXAMINING BALLOONING STADIUM COSTS

Assuming that the LCA has a lifespan of 30 years, it’ll work out to $31 million per year in cost, which is nearly double that of the shortest-lived stadium on my list. The lifespan of the most expensive stadiums in the US, which are all for football, save New York’s new Yankee Stadium, is unclear, as most of them are pretty new. (Interestingly, almost all of the most expensive stadiums in the world are in the United States, save for a couple of UK football-they-really-mean-soccer stadiums).

But let’s look at those costs and let’s assume, quite optimistically, that they have 40-year lifespans.

- Allegiant Stadium, Las Vegas, Nevada. $1.9bn (2020), $47.5m per year.

- MetLife Stadium, East Rutherford, New Jersey. $1.7bn (2009), $42.5m per year.

- Mercedes-Benz Stadium, Atlanta, Georgia. $1.5bn (2017), $37.5m per year.

- Yankee Stadium, New York, NY. $1.5bn (2009), $37.5m per year.

- AT&T Stadium, Arlington, Texas. $1.48bn (2009), $37m per year.

Notably, these costs are several times higher than the stadiums of yore. They’re also higher than the LCA. This isn’t to say that the LCA was a bargain. It’s to say that the costs of these stadiums are outrageously high and that taxpayers shouldn’t be expected to shoulder the burden of paying for them, nor for figuring out what to do with them after the team gets tired of them in a few years. They’re also not even good economic propositions, referring back to the whole book written about this. Silver bullets are so passé.

To be perfectly clear: It’s not as though the difference between a billion-dollar stadium and a half-billion dollar stadium involves some sort of moonrock-powered, zero carbon hyperloop to transport drunk Cowboys fans to the stadium from downtown. Nor is a billion plus dollar expenditure required for things like ADA accessibility. Rather, costs are driven up by shiny amenities like more restaurants, tiltable seats, retractable roofs, or the LCA’s “gondola” seating (suspended from the superstructure with glass balcony walls).

ENERGY SPECIFICS

One member of Olympia’s team didn’t even seem too excited about the Arena from an operational standpoint, suggesting that there might be some major deficiencies that he didn’t really get into. Cooling load in a packed stadium on a hot day becomes problematic. 19,000 fans produce some ten million plus BTU’s of energy from body heat, which is equivalent to about 120 residential-sized forced-air furnaces, plus moisture from respiration. That’s kind of wild.

The building is also built below grade. Even the best pervious paving on the outside, though, can’t compete with a water table, and this is admittedly something well beyond my limited understanding of hydrology. The building has a number of sump pumps to keep the “basement” level dry. The electric bill is in the six figures per month. LCA folks declined to give figures about EUI, but I bet it isn’t pretty.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE EXPANSION PLANS

I’m impressed with the building– don’t get me wrong. It’s beautiful. It has, along Woodward, a nice relationship with the street. It’s also got a lot of potential for future expansion and improvement. But as far as the sustainability thing, I’m really not sold. Docents lamented how hard it was to get LEED Silver. It seems like a lot of the points gained on the scorecard were from location— and things like automated lighting. The building barely has recycling (hey, Michigan!).

Ain’t no two ways about it: ODM gonna ODM. They’ve continually delayed their vaunted residential projects. It’s unclear whether any of them will actually happen. They continue to enjoy favorable terms for land swaps. They continue to allow derelict buildings to rot. And they continue to mysteriously avoid compliance with the city’s vacant property ordinance.

But the city is going to move– even if ODM doesn’t.

Conversion of parking lots to buildings? Taxing individual off-street surface parking spaces and using the money to fund free transit? Maybe. Incentivizing development in front of Comerica Park fronting on Woodward Avenue? Seems unlikely. Here’s one idea beyond proximal real estate development, which would be near-impossible to effect on Ilitch-owned land.

One idea is to build a “lid,” or “cap park,” on top of the freeway here. The lack of access ramps here means that this wouldn’t be terribly difficult, in the scheme of monumental urban design projects. This gives you a roughly seven-acre park. Adding the 6-8 lanes of service roads on the north and south sides adds another few acres.

This was done with great success in St. Louis and is gaining popularity— as cities start to wonder why the hell we sliced up our downtowns with freeways in the first place. Imagine a few thousand trees in place of a noisy landscape of concrete and asphalt. A similar project is in the works in Pittsburgh. This would have amazing implications for improving connectivity between downtown and Midtown. It would result in cleaner air, lower ambient noise levels. It would sequester carbon and reduce ambient summer temperatures, also blocking wind in the winter.

I’m hopeful. I’m also hopeful I might be able to attend a Red Wings game once I get a real job and start making the big bucks (hey, you’re always welcome to help out!). Is it impressive? Yes. Sustainable and glorious? Not so much. I just hope we learn some things as we see this building age in its surrounding sea of parking lots. This will especially be important as we move into high transit season, keeping fingers crossed for RTA expansion.

Great running into fellow USGBC co-conspirators Lindsey Elton, who heads up EcoAchievers, and Kelly Adighije from Chicago-based Baumann Consulting. These folks are doing great work and I’m glad to announce that Lindsey is on board with our transit coalition as well!

(Olympia Development did not initially respond to several media inquiries, but finally responded on January 28, 2020 after the date of publication, citing a Free Press article from 2018 mentioning that Chris Ilitch was a signatory to a CEO letter supporting transit expansion. It is unclear whether Olympia has been involved in further efforts to promote transit expansion, though they have demolished a number of buildings in recent years to build more surface parking space).