Detroit Park City No. 6 – Eastern Parket District

Market districts are kind of a fun thing. The idea is that instead of having a single building dedicated to a market, you have an entire neighborhood. In a single building, one runs the risk of losing what I’ll call the “primary food production” element of the commercial mix. If rents rise, a market can become bougified. This can push out smaller businesses, say, a mom-and-pop butcher, in favor of what I call “secondary food production,” a.k.a. a business owned by suburban college graduates who live in a McMansion and sell organic wheat grass made in a suburban commercial kitchen. You know, Macron’s Macarons, or something. $6 each– but honey, they’re USDA certified organic!

In comparison, a district can be managed to include and preserve a mixture of uses focusing on one specific one. Historically, this was a matter of economic clusters being built around specific background infrastructure or competencies. Manhattan typified this in days of yore: think “meatpacking district” or “garment district.”

DISTRICT MANAGEMENT

Having a nonprofit or quasi-non-governmental organization to help guide development can help maintain the primary food production focus and can also encourage new business growth while managing some semblance of equitable or pluralistic economic development.

In contrast to, say, the Soulard Market in St. Louis (since roughly 1779), which operates solely as a market but enjoys proximal related businesses, or, in my hometown, the Lancaster Central Market (1730), the idea of a “market district” is not new. But clever management of it is important. Nonprofit organization Strip District Neighbors in Pittsburgh does this for the eponymous market district along the Allegheny River. But this district only developed into the food/market economy relatively recently in its roughly two century life. Detroit’s Eastern Market has been operating in its present location for about 130 years, when the city’s major market function relocated from an increasingly crowded downtown, and the past half century has seen the growth of an expansive economic cluster around food production.

Locally, Detroit’s Eastern Market Corporation exists to guide development activities and support business growth in the district. A recently released implementation plan highlights future plans for the district including infill and revisions to how parking is managed. As the district thrives overall, one is left with the impression of effective guidance and management by EMC. Exceptions might include allowing the bungled management by suburban rich kid Sanford Nelson as he jacks up rents and expropriates long-time tenants, like the iconic Russell Street Deli, whose soups, sandwiches, and breakfast plates were renowned throughout the land. But, overall, the Eastern Market, as long as I’ve been hanging out in Detroit, remains a diverse, vibrant, and thriving mini-conomy.

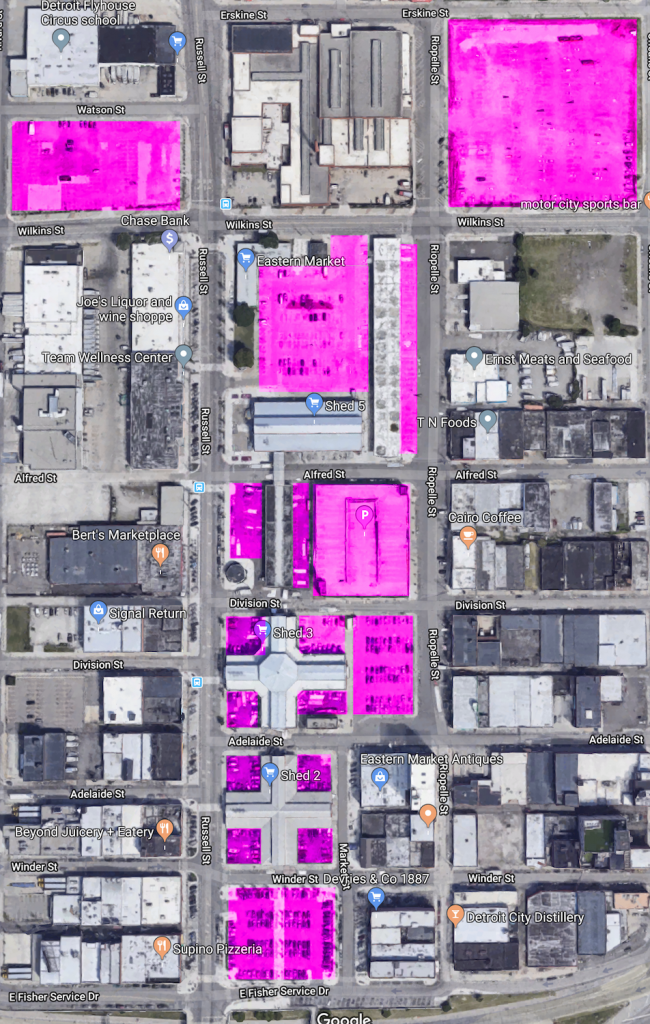

It remains, however, unfortunately addicted to the automobile. Though this may be changing, the district is heavily dominated by surface parking.

There are five principal parkingscapes in the district that serve customers and businesses alike. Virtually all of the parking is free. There is also a parking structure. (By odd coincidence, the parking structure is, eerily, nearly identical in dimensions to the parking lot serving the Eastern Market offices).

Like the Post Office lots, these lots do not pay taxes because they are publicly owned. They do, however, pay drainage fees. The drainage fee, maligned as a “rain tax,” is being phased in over several years to fund stormwater infrastructure improvements in an aging system. It has not been popular, though it is crucial to disincentivize the development of land into parking– and, rather, incentivize its development into productive uses.

David Tobar, ASLA, President of Eastern Market Development Corporation, suggested that there was a strong possibility that the city would implement paid street parking in the near future. He did not indicate that the off-street lots would become paid parking, but rather that it was likely that the city would begin metering street parking in order to better regulate what has been used and abused as a (heavily subsidized) public good.

“You’ve got 200 food businesses that employ thousands [of workers], and they may park in front of a retail area because it’s close to work,” he said, “but there’s no incentive to move their car after a few hours. That impacts retailers.”

He noted, in agreement with what I learned from APTA in Tampa, that retailers who are reliant on foot traffic are far more likely to be in favor of paid parking in front of their business because turnover of spaces is good for bringing in prospective customers. The Shoup has also noted this in Parking and the City, as the idea of regulating parking spaces as a perishable commodity rather than a public good allows more of us to get what we want as far as mobility in general, and parking spaces, more specifically.

Tobar did not know of any conversations around connectivity with DDOT’s nearby bus route (Gratiot). A representative of the city’s urban design team working on the project said that transit connectivity would likely be revisited in future iterations of the plan, especially as part of considerations of denser residential development. One notes that Gratiot is less than 1/4 of a mile walk from the southernmost Shed at the market, putting the market well within the walkshed of the bus line. It is nearly a half mile from Wilkins St., on which our largest parking lots sit, to Gratiot.

THE SITES

With the exception of one parcel that is county-owned, the rest are city-owned. The parcels are a bit of a patchwork, though, because the boundaries don’t exactly correspond with a street grid that has changed over time. Along with the non-taxable nature of the city-owned parcels, this makes the sites unsuitable for apples-to-apples comparisons.

South lot: 2440 Russell (99 spaces on the southern lot and an additional 175 throughout the rest of the market area on this same lot, separate from the office lot (below).

Eastern Market office lot: 2934 Russell (about 140 spaces).

Northeast lot: 3101 Orleans, 3085 Orleans, and 1580 Wilkins (about 500 spaces– a whole city block).

Northwest lot: 3033 Russell (about 180 spaces).

Parking structure: 2727 Riopelle. This has about 300 parking spaces.

So, the entirety of Eastern Market’s central lots that are publicly owned and operated ostensibly for the benefit of marketgoers occupies about 16 acres and includes about 1400 off-street parking spaces, to say nothing of street parking spaces.

Because none of this land is taxed, the parking lots effectively amount to a massively publicly subsidized resource. Tobar confirmed that Eastern Market Corporation was paying drainage fees as part of its water bill assessments, which, based on my calculations, will come up to a cool $12,000 per month by the time the drainage fee is fully phased in. That’s a chunk of change. But Tobar notes that new development has the opportunity to incorporate pervious surfaces and water-retentive plantings that could substantially reduce this fee.

TRADEOFF ILLUSTRATION

1400 parking spaces, then, represents the equivalent of about 799 apartments built one story tall. Or 2,038 units built three stories tall. That represents somewhere in the vicinity of $8-40 million per year in rental revenue, depending on how you’re calculating. In other words, that’s tens of millions of dollars of economic product that the city is missing out on, instead having this land occupied by parking.

We should at least expect the Market to recoup the cost of drainage. This means that each parking space has to provide $102.85 in net revenue per year. That’s not much money. Napkin math: ($0.25/hour) * (3 hrs. / day) * 365 = $273.75 per year. At $2 per hour, that’s $2190 per space per year. Should taxpayers be annoyed that Eastern Market is forgoing $3.07 million per year by subsidizing that amount in free parking?

I mean, I certainly think so.

Parking pricing should be set– possibly dynamically- to ensure that, even in high demand times, drivers can find parking, but so as to maximize occupancy of paid parking. In other words, you don’t want there to be too many empty spaces, but you want there to be some spaces available at any given time. Eastern Market parking is always pretty easy to find. Making parking harder to find is a good way to incentivize alternative modes of transport. Like, I don’t know. Maybe one of the multiple bus lines that go there.

THE PROJECT

First, refer back to the implementation report. Infill is mentioned. Parking is also mentioned. What is not mentioned, interestingly, is transit connectivity. The Gratiot bus line is one of the most trafficked transit routes in the state of Michigan and is only two blocks south of the southernmost parking lot. But it mysteriously has evaded mention in the entire planning document. A representative of the urban design team working on this project said that he imagined that mention of transit connectivity would be included in future reports, but referred questions to the city’s mobility office, which had not responded to a request for comment as of the time of this article’s publication.

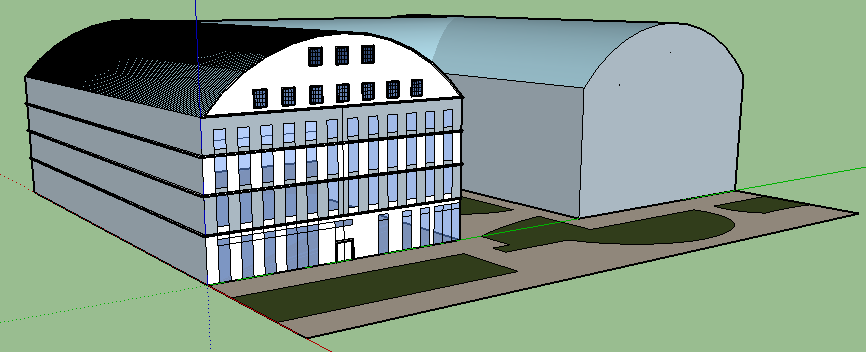

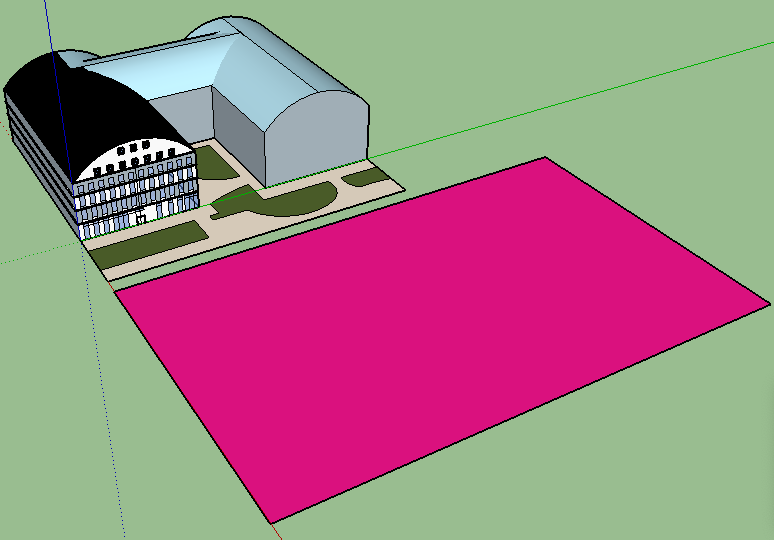

We have a whole collection of lots to work with, so I don’t need to think about every space. The image below is a proposed design for the southernmost lot. We’ve noticed again that I’m not an architect. But, indeed, this design turns 99 spaces into a hundred some apartments.

A 0.88 acre parking lot thus becomes a 190,000 square foot building with 170 apartments. Unfortunately, given current parking requirements, this building would then require its own parking lot that would be more than two acres (see below). Recall the post office example, where it became fairly clear that building so densely without addressing parking minimums would make development unfeasible unless one wanted to pave over, quite literally, the entire riverfront.

Interesting will be to see how fast development can tap into the implementation plan’s proposal to build above existing structures. This is not the type of adaptive reuse that typically happens in postindustrial Midwestern settings. But it could add a ton of housing to a neighborhood that utterly lacks it beyond a handful of lofts.

Not to mention that it’d be a great excuse to replace the leaky roof of my favorite antique store. Disirregardless, as it were, more density within an important transit corridor wouldn’t necessarily strain Eastern Market’s parking demand. It just needs to be priced correctly. At present, priced around the affordable zero dollars, that isn’t going to change anyone’s mind about their reliance on their automobile.