Cadastral Projection: Exploration In The Time of the Rona

Cadastral Projection is a new project that uses a Matterport camera to connect vibrant spaces around the Midwest with would-be visitors, clients, and customers during a time when the COVID19 pandemic is limited our ability to interact with each other in person. This project is specifically focused on spaces that have historically evaded the platform, which is typically used for higher-end real estate, and we’re interested in We are pleased to announce that we have received generous support from the Matterport company to pursue this project.

Background

We’ve been working with Matterport for a few months now and have already provided imaging services to dozens of clients around the Midwest including Dubuque’s impressive Steeple Square adaptive reuse project and Ford Motor Company’s Michigan Central Station. The camera takes high-definition digital images while also measuring a space. I wanted to use it for a bunch of different things, but I was chiefly interested in using it for energy consulting work. A chunky block of equipment with several cameras that allow it to capture multiple angles at once and a stepper motor that rotates the camera around for six individual scans, it’s relatively easy to use, and a seamlessly integrated platform and AI stitch together images and measurements to create things like floor plans. I realized that the market for Matterport was well-developed in the space of million-dollar real estate, but rather underdeveloped in terms of a much broader level of potential.

On a whim, I wrote to the company, suggesting some ideas for how it could be used to promote things like community engagement, education, or even urban design. I was able to schedule a call the following week with Linda McNair, Matterport’s Director of Content Marketing, and we spitballed for a bit. Over the next month and some, I was able to tour a bunch of spots, many on a road trip to a (socially distanced, outdoor, very tiny, not-superspreader) wedding in St. Paul. I interviewed entrepreneurs, business owners, coworking tenants, food service workers, and manufacturers. I was chiefly interested in the spatial question of COVID19 and how companies are managing (or struggling).

The Struggle Against Empty Space

In September, I spoke with the owner of Eclipse Records in downtown St. Paul. I had been to a previous iteration of the record store, which has roamed the city nomadically since its opening decades ago. He said that it’s been tough since they can’t host shows, although they have a great venue space in the back of the shop. I also thought about this in talking to a colleague at First Avenue, a legendary Twin Cities music venue that has virtually lost all of its business since the pandemic hit. Matterport can’t fix the plight of these spaces. But it can provide a good way for people to remain connected with them when they can’t physically occupy them. It is also my hope that this will facilitate the development of new avenues for expression and engagement. Many of these things people are already doing. Think: livestreamed DJ sets or concerts. Curated spaces that feature special content for some specific event or sale. Interactive content beyond just watching something passively.

Ok, what’s with the name?

Cadastral Projection is a pun on, or portmanteau of, really, “cadaster” and “astral projection.” Astral projection you may be familiar with. It refers generally to an out-of-body experience in which a human projects one’s spirit or mind, well, somewhere (as an astral body, a.k.a. “not the actual human body”).

The cadastral part is a bit trickier. TLDR: urban planning and economic geography nerd stuff. Indulge my academic nerd in a history lesson.

“Cadaster” comes from the Greek katástikhon (κατάστιχον), “kata” (“down” or “against,” like “catastrophe” or “katabatic”) and stikhon (“line”). This may well be the same root as the English “stick,” which comes from a Proto-Germanic root that sounds an awful lot like “stikhon.” Language is wild like that, and no, I should not go back to school to become a linguist, I already have enough degrees and enough debt. Anyway, I guess a katastikhon is like some sort of list or a register used to record land stuff. A writing-down of sticks? Yeah, I’m not a linguist.

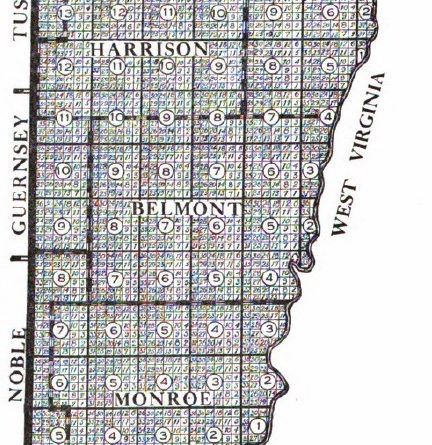

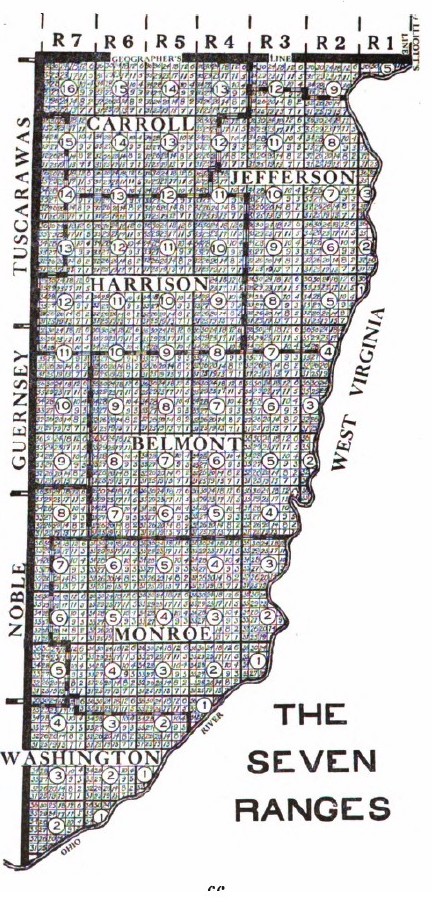

Anyway, the cadastral survey refers to a method of measuring and delineating land. The American rectilinear cadaster was the one-mile by one-mile surveying square developed by Thomas Jefferson in 1785. Jefferson envisioned a land of yeomen farmers– a great democracy and everyone would own 640 acres square! This was kind of a cool idea in 1785. Cool academic idea though it may have been, it represents a successful and in many ways rather monstrous attempt– endemic of the Enlightenment obsession with rationality- to impose man’s control over nature. 1776 produced the American Revolution and Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, and 1785 produced a land survey model that would essentially commodify land itself. It is perhaps not surprising that these things were direct products of Enlightenment thinking. I mean, the man himself, René Descartes (1596-1650), invented what we now call the Cartesian coordinate system. It is, well, hard to imagine space and time without this system. This is largely a product of how obsessed we’ve become with rationality as a society in the pursuit of money, that awful, ubiquitous, universal equivalent.

The WPA pavilions at Eagle Point Park in Dubuque, Iowa, which we scanned for the City of Dubuque. A full write-up on the park and architect Alfred Caldwell can be found here. The Prairie School, of which Alfred Caldwell was called the “last” architect, was very interested in rectilinear and expansive, lateral forms that were frankly more evocative of the grid and flatlands than they were of the rolling hills of northeastern Iowa.

The American Square

This survey model is why most of the roads in the middle states cut through at straight angles. I became a little bit obsessed when I discovered this history in Hildegard Binder Johnson’s Order Upon The Land (1978), which is as much about Midwestern American culture as it is about the land survey. Among many other things, the German-American geographer looks at the imposition of unnatural order onto land that doesn’t necessarily lend itself to, well, being parceled off into squares. Johnson wasn’t looking at pre-colonial history, but it’s worth noting that the white colonial mindset was at fundamental odds with native people’s perception of the natural environment, certainly as much as the rectilinear cadastral land survey model was at odds with the natural curvature of the lands and waters. The square is a solid metaphor for this conflict, as “squaring” the natural environment in many cases resulted directly in savage violence against people and destruction of the natural environment.

Hannah B. Higgins commented that the “persistence of grids demonstrates that once a grid is invented, it never disappears. At least not yet.” The art historian weaves a tight slalom between grid as a literal construct and the metaphorical implication of the grid as a human imposition of rational order– and, perhaps most interestingly, what happens when that grid is broken or challenged. While Higgins’ work, The Grid Book, is mostly spent elegantly tracing a history of the square through a range of historical artifacts, artistic expression, print, and their context, she begins with an acknowledgment of Catherine O’Leary’s cow who, kicking over the lantern in the shed whilst being milked, started the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Higgins sees the cantankerous cow’s act as an ultimate challenge to the order of the grid. And there are few cities in which the grid is as omnipresent as in Chicago, with every major street neatly separated by a half mile.

Project Yourself

If we bring Higgins’ lessons into the age of the rona, the persistence of the grid means that when we aren’t able to physically occupy spaces, we still occupy a society built around that grid and around those spaces. We think in terms of road routes to get from here to there. And we still, of course, have to deal with the cost of space and the built environment, perpetually recorded and analyzed in gridded spreadsheets. Matterport can’t uninvent some of these things, nor can it even challenge them. But it can provide a somewhat disruptive approach to understanding our need to physically occupy itself. Project yourself– and follow the series as new spaces are published.

Cadastral Projection is funded from different sources including the generous support of the Matterport company, consulting and ad revenue, and the financial support of contributors like you. Got a space you want to highlight? Get in touch!

In Detroit’s New Center neighborhood, Yum Village is an Afro-Caribbean restaurant, the brainchild of mortgage banker-turned-entrepreneur Nigerian-American chef Godwin Ihentuge. The restaurant occupies a space in an Art Deco façade storefront on Woodward, formerly occupied by a Popeye’s. Check out the full article here.