Tour of Ford’s Michigan Central Station Project

Michigan Central Station, the iconic, hulking, centenarian structure that has sat vacant for decades, is perhaps the flagship redevelopment project of Detroit. The redevelopment, led by Ford Motor Company, is also a kind of synecdoche for the future of Detroit vis-a-vis an auto industry trying to reinvent itself. While Ford isn’t exactly hurting for cash, the company has in recent years stared down a transportation sector recession, drastically and controversially reconfigured its product lineup, and tangoed with an impetuous presidential administration that can’t decide whether it wants to defer to big business or reign over it with a debatable level of competency. The train station itself heralds a transformation in how Michigan’s vastly suburban automotive economy is rethinking its context in the region’s built environment– the project can be contrasted with Ford’s historically suburban campus in its native Dearborn- as the sector grapples with a future where people are more likely to favor denser urban living, walking, biking, transit, and micromobility, over the leased-F-150-driving, vinyl-sided-suburban-living paradigms of yesteryear.

Last week, I had the opportunity to get up close and personal with the project. I toured with Ford Land architect and site project manager, Gary Marshall. Gary worked with Dearborn-based Ghafari before moving to Ford Land, where he worked on manufacturing before transferring to the MCS project.

A TALE OF TWO TRAIN STATIONS

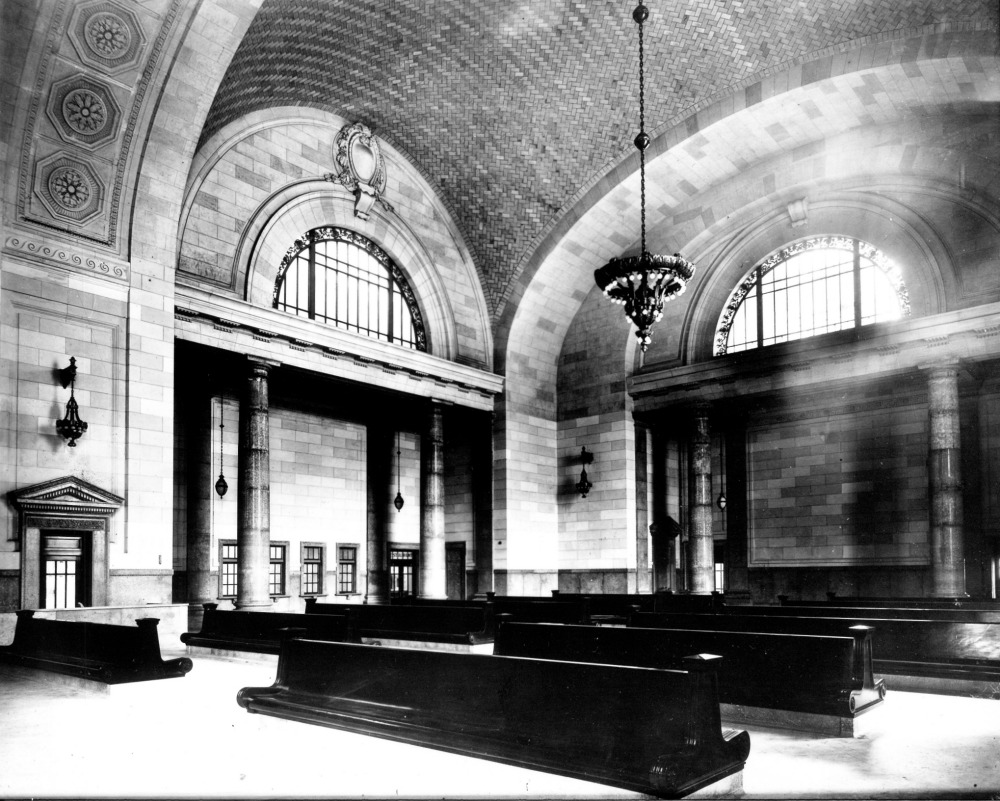

The train station was built in 1913 at a staggering cost of around $400 million in 2020 dollars. Detroit was booming at that time, and the supreme reign of the motorcar would not come to decimate public transit for many years. The architects were legendary firm Warren and Wetmore, Beaux-Arts champions and progenitors of New York’s Grand Central Station (also 1913, and also in partnership with engineering firm Reed & Stem). Just as Grand Central was threatened with demolition from 1954-1978, the great age of urban renewal (N.B.: “wholesale demolition of historic inner cities”), Michigan Central was similarly threatened with demolition as recent as 2009. Any good city planner can tell you about the landmark supreme court case, Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City, 438 U.S. 104 (1978), in which a virtually-defunct railroad tried to salvage its balance sheet by reviving a decades-long dead horse of a proposal to demolish most of the historic New York train station and build an office tower inside it. Detroit’s city council, at the behest of Ken Cockrel, Jr., Monica Conyers, and Barbara Rose-Collins, among others, pushed to demolish the building– and lien the Morouns for the cost. This plan never materialized, thank goodness. The Ford plan, meanwhile, emerged out of what appeared to be thin air, following years of ownership by the languid Moroun development empire, which has focused more on manipulating land into profitable deals, often at public expense, rather than on proactively improving urban community.

Colleagues within Ford have told me that the company’s executive leadership was less excited about the project than its biggest proponent, Bill Ford, the great-grandson of the man himself. The Ford family to this day retains an enormous voting power in the company, owning around 40% of voting shares in spite of maintaining a small percentage of equity. While I’ve met some onlookers skeptical of the project, either as a matter of feasibility or of its ability to appropriately fit into its urban context, I have yet to meet someone who thinks it’s a bad idea. Put differently: Most people are excited to see this come together. It is important to take note of the comparison between managerial leadership and long-term vision for corporate legacy here.

MICHIGAN CENTRAL, DENSITY, AND URBAN CONTEXT

The Michigan Central Station occupies a giant swath of land on what is generally considered to be the edge of Corktown proper, separating it from what one might call Near-Southwest. Corktown is a neighborhood that, like many other neighborhoods, suffered a large amount of population loss, but has since stabilized and become, well, largely unaffordable. Now, boxy new construction peppers a landscape comprising the neighborhood’s characteristic, brightly-colored, ornately trimmed Victorian-era homes. While the pace of development has plodded along slowly, a number of newer businesses have found strong footings, sticking around even through the economic mess of COVID.

In the fall of 2016, as the Corner redevelopment project was kicking off, I wrote about Corktown’s “Iowa farm town” levels of density (“Low-Density Redevelopment of The Most Iconic Vacant Site In The City Is Just So Detroit”). In that article, I wrote:

“According to LOVELAND’s Motor City Mapping, Corktown, considered one of the “coolest nabes” in Detroit (…don’t say that, by the way), has a mere 449 structures, of which only 359 were definitively occupied as of their last survey, and 386 vacant lots. CityData counts 1,069 residents at a pleasant, Iowa farm town density of 2,604 people per square mile (about half of Detroit’s average), while Data Driven Detroit counts 1,196 residents (with slightly different boundaries). As I’m all about understanding how perception or misperception informs decisionmaking, I’d just point out that this density is pretty low.”

Fast forward to 2020. Tony Soave’s Elton Park is finished and, though I’m fairly sure I’ll never be able to afford renting a unit there, it doesn’t look half bad as a matter of context and architecture. At full occupancy, the project represents a population increase of as much as a third over Corktown’s 2016 density when I wrote up the Tiger Stadium redevelopment. The Tiger Stadium apartments, townhouses, and Elton Park combine represent as much as a two thirds increase from 2016. It sounds like a lot until you realize that there wasn’t a whole lot to begin with from a population standpoint. From a city planning perspective, this level of density is still anemic– less than a third of the density of Detroit’s West Village neighborhood, for example, where a large number of multifamily apartment buildings combines with a near-zero vacancy rate, or of Hamtramck, where historically larger families fill homes packed into a dense street grid.

Graffiti– whether intentionally and overtly destructive, or objectively artistic- forms a period of the building’s history, regardless of whether it conforms with the Secretary of the Interior’s standards, yadda yadda yadda. That the building was abandoned amid a nationwide decline in infrastructure, and many of its surfaces defaced– or decorated- is as significant a part of its history as the role it formerly played in transportation.

Ford has remained relatively quiet about what it wants to do about the surrounding space– but there’s certainly a lot of it. The train station itself was built over a clumsy amalgamation of parcels, whose plats still remain active in the city’s parcel tracker. The building itself takes up a footprint of about 100,000 square feet (~9290m^3). That sounds large until you sum the area of the former platforms, tracks, and adjacent vacant lots, which take up a combined total of about 10 acres (~4 ha).

COMPETING NEIGHBORS

Sources tell me that landowners eager to cash in have already approached Ford about selling parcels at egregiously inflated prices. The problem for these landowners is that when you– Ford- already control such a large area of buildable land, you aren’t hurting for land. So, have fun with that, I guess. Corktown has long been a hotbed of speculation as Detroit’s “up-and-coming” neighborhood. I used to have coffee with people in 2014 and 2015 who would fly in from New York to prospect deals. They weren’t very good at it, though. They would look at occupied properties in Corktown that they then wanted to gentrify– after paying a crazy high price. Such is the problem with cultural ineptitude in a real estate development regime. My maxim has always been that if some Brooklyn punk in designer boots and a slim fit suit is telling you about so-and-so neighborhood being “up-and-coming,” it already done up and came. Long, long before he took a sip of that organic lavender latte, or whatever. But I digress.

BFD Corktown, LLC, for example, owns the CPA Building at 14th and Michigan. Its mailing address is a residential address of a multi-million dollar home in North Jersey’s distant suburbs of New York. Downtown Detroit law firm Butzel Long is the registered agent for the mysterious shell corporation owner of another small parcel next to the train station. That parcel’s last sale price was listed as $420,000 in 2017, before it was more recently quit-claimed between shell companies. WCRD termed it a “valid arms-length” transaction, which it clearly wasn’t if it was transferred for $1 between two companies with the same registered agent. Curiouser and curiouser. But so it goes.

HISTORIC PRESERVATION AND ITS DISCONTENTS

While much of the building’s historic character remains, individual fixtures have been extensively stripped in the past 30 years. The station was shut down in 1988 and sold to a real estate developer in 1989. That developer’s plans never materialized, and the Morouns bought it in 1996, by which time a great deal of the structure’s historic interior had been scrapped– including antique chandeliers and lighting, tile, ornamental terra cotta, stone, and furniture. By the time I first visited Detroit in 2011, there wasn’t much left of the original building, save the façade and major structural elements. It was at that time open to the elements– and to anyone who wanted to take a tour inside, for that matter.

The project’s use of tax credits will necessitate fairly exacting restoration of the original design. But a lot has changed, so there is always a question of how much must be restored. Historic preservationists typically take the tack that a historic restoration need restore every last detail down to the material properties and construction techniques. I’m on board with this attached string as a general requirement for people receiving tax credits. I’m less of a fan of historic districts because they say “no” more than they say “yes.” Or, put differently, historic districts usually say “no” instead of “let’s figure out a way to make this work.” My neighbor, for example, has vinyl replacement windows. He doesn’t have them because he wants to offend the historic preservationists. He has them because he can’t afford the cost of exorbitant restoration. He also isn’t receiving tax credits for them.

In the Michigan Central project, however, some element of ambiguity in some of the spaces. Would historic preservation necessarily have to cover over a particularly elegant graffiti mural painted on a wall, for example? Graffiti– whether intentionally and overtly destructive, or objectively artistic- forms a period of the building’s history, regardless of whether it conforms with the Secretary of the Interior’s standards, yadda yadda yadda. That the building was abandoned amid a nationwide decline in infrastructure, and many of its surfaces defaced– or decorated- is as significant a part of its history as the role it formerly played in transportation. Indeed, one might take this argument

I related this thought to architect Gary Marshall when I asked whether Ford was going to be preserving certain spaces in their current state as opposed to restoring every square inch meticulously. This is one thing Dan Gilbert’s Bedrock property regime has done a great job of. I’m thinking about the First National Building, an obscenely ornate, columned tower at 660 Woodward. The lobby features sweeping, modern installations and seating as well as both historic accoutrements and even the structural underpinnings, exposed for all to see.

EPILOGUE: CORKTOWN AS MOBILITY CAPITAL

On the mezzanine level, massive steel beams had been lifted into place with cranes to support various scaffolding and steel frameworks. Bright blue tarps anchored to rusted steel work undulated gently in the breeze. We had to hike up to the sixth floor because the elevator was temporarily out of order. I huffed and puffed, my yellow Pelican case occasionally blending in with lurid graffiti that evolves across each level of the stairwell.

While Gary was showing me around, I tried to get my head around the order of operations. Coming from a residential construction background, I understood the principle, but not necessarily the execution. Gary wasn’t exactly the most loquacious tour guide, but he did his best to tolerate my incessant line of questioning. (I was, to some degree, like a kid in a candy shop). He did indicate to me that the number of staff on site is going to steadily increase over the next several months. When we were there, a crew of about 40 were on site, working on everything ranging from plumbing to electrical to steel repair. The building will eventually need some sort of gargantuan heating system. I find myself thinking about whether the Secretary of the Interior standards would permit a flash-and-fill double-studded wall cavity. (Probably not).

The train station project is expected to be done by 2022. Whether it will again serve as a train station is a matter of considerable debate. I am hopeful, but not holding my breath. I’d love to see some sort of institution that can facilitate a variety of forms of mobility including fixed-route, autonomous vehicles, micromobility, and, I dunno, bikes. Some of this might come from Ford, but a large portion of it has to come from bigger players. The current presidential administration seems to have no interest in restoring the country’s ailing infrastructure. In the unlikely event that they win the 2020 election for another four years, we probably can only look forward to an increasingly privatized, increasingly automotive transportation paradigm. However, Joe Biden is a proud Amtrak rider, so who knows, right?

Most people in automotive have acquiesced to the inevitability that we won’t all be driving Fords F-250 Super Duty that we individually own in the future. But the future of mobility beyond that is rather murky. Well-developed fixed-route transit is elusive in a state that thinks trains and buses are a Communist conspiracy. (One colleague’s Facebook friend, a former elected official from a western suburb, called the Regional Transit Authority a “Mike Duggan socialist power grab”). On paper, Ford ostensibly supported the RTA but none of the automotive companies put any muscle into supporting the push for regional transit investment whatsoever. Instead, the company– like its peers- has invested billions in autonomous vehicle development. Autonomous vehicles are an unproven technology still in its infancy– with not much in the way of a clear path toward profitability. (Notably, Wayne County previously declined multiple requests for comment on a related story about transit connectivity planned at the new station).

NEW DAY, NEW MOBILITY

But will consumers prefer “Mobility-as-a-Service” to reliable, affordable, fixed-route systems like buses and trains? My car has cost me $25 this past weekend in insurance alone and I haven’t driven it once. On the other hand, DDOT suffers from low ridership numbers and only recovers around 15% of its expenses through fares. In densely populated cities, this number can top 100%, as it does in Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor. It’s entirely possible– with the right amount of density. But $25 is, well, a 0% farebox recovery ratio. I’m not getting that money back.

I’m really thinking it’s not an “either/or.” I’m ever the fan of the Great American Road Trip. I also enjoy being able to take stuff in my car and go camping or bring my bike or whatever. And finally, I have a lot of rural roots that wouldn’t even be accessible with most fixed-route systems. But implicit in the monumental nature of a project like this one is that the future of mobility is going to be definitively more urban than the likes of Ford’s Dearborn campus. (And don’t even get me started about FCA in Auburn Hills!). Part of this is a generational shift, of course. Millennials returned to the cities their parents or grandparents fled. And “urban” is going to inevitably involve figuring out ways to move more people more effectively– and in a cost-effective manner. Autonomous vehicles might be able to wangle the road trip, but they’re not going to replace the bus.

Whatever the project ends up looking like, Michigan Central Station is attractively positioned. Close to downtown and fronting on what the state plans as a new “mobility corridor,” the site bears a great deal of potential for That Which Is To Come– in terms of mobility and transportation, certainly, but also in terms of economic development, architecture, housing, and so many more things. I’m enormously excited about the possibilities here, and I remain cautiously optimistic. Hoping to get some more images of the station as construction progresses, and I’m also looking forward to remaining actively engaged in the process of working toward an equitable, sustainable future for mobility.

More information about Handbuilt’s Matterport imaging services can be found here. Color photos are the exclusive propriety of Nathaniel M. Zorach / The Handbuilt City, LLC and are licensed along with the Matterport imaging (as stipulated under the user agreement with that company) to Ford Motor Company and Campbell Marketing, Inc. Black and white historic photos are from the Detroit Public Libraries, via HistoricDetroit.org. Snarky commentary contained herein does not represent the opinions or positions of Ford Motor Company, Campbell Marketing, or their subsidiaries or affiliates.