Suburban Skylines: A California Tech Town’s Growth Struggles

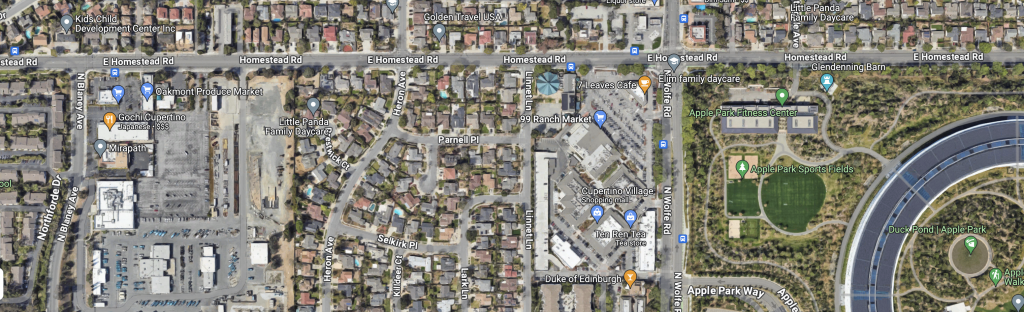

In some sense, Cupertino, California is hardly special. It’s a classic postwar suburb with leafy subdivisions of single-family homes connected by arterial roads and freeways and a population of 60,000 people. An hour south of San Francisco, it embodies all of the historical trends that characterize American suburbia. But Cupertino also is special, forever transformed by the growing tech industry, which has forced a reconciliation with how a suburb can accommodate rapid growth. Known for the world headquarters of the technology giant Apple, it is a major job center in its own right within Silicon Valley. It also experienced America’s growing diversity. Beginning in the 1980s, it saw a rapid growth in its Asian American population, drawn by high-performing public schools and proximity to the tech industry – first Taiwanese and Hong Kongers, followed by Indians and mainland Chinese.

As Cupertino has grown to accommodate that diversity, it’s experienced a clash of modern urban form – high density on boulevards with largely single-family neighborhoods. With potentially better transit and denser housing on arterial roads coming, the challenge of Cupertino is managing growth in a city with mostly single-family zoning and limited desire to change that. But for some suburbs like Cupertino, this isn’t as dramatic of a shift as it sounds. In the midst of a national housing crisis, suburbs will have to change, and the battle for the soul of these suburbs may pioneer a new type of urban form.

Lawns and encampments

Cupertino is also ground zero for California’s housing crisis. A poignant symbol of the housing crisis emerged in Cupertino: a homeless encampment in the shadow of Apple’s gleaming headquarters.

The battle over affordable housing offers a glimpse of what could be possible and what challenges lie ahead. Redfin estimates that homes in Cupertino sold for an average of $2.4 million in December 2022, among the most expensive in the Bay Area. Its growth has leveled off in recent years, with population increasing only 1.6% between 2010 and 2020, compared to a growth rate of 8.6% for the San Francisco Bay Area as a whole. The housing stock has only grown 0.1% in this period despite high demand for access to education, jobs, and other resources in Cupertino.

This slow growth has not kept up with the rapid growth of the tech industry. The state of California calculates how much new housing cities should build based on existing need and projected growth through a process called the Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA). California then requires each city to plan for this amount of housing and document feasible sites in the state-mandated Housing Element. Cupertino has fallen far below its RHNA targets, having issued permits for only 13.5% of its target for 356 low-income housing units. In total, the city issued permits for only 418 total units between 2015 and 2022, out of a target of 1064 units. (The figures on the total demand for housing in the Bay Area at large are staggering).

The lack of housing, particularly affordable housing, has hurt Cupertino and the greater Bay Area. The renowned Cupertino Union School District closed two elementary schools in October 2021 due to a 17% collapse in enrollment. Nonprofit Silicon Valley Community Foundation attributes these closures to demographic changes and high housing costs– young families with children simply can’t afford to live here.

Impacts have been especially severe for low-income workers and community college students. Local housing advocacy group Cupertino For All links high housing costs and exclusionary policies to increasing rates of homelessness and displacement of working-class Bay Area residents. It points to the extremely low ratio of low wage jobs to affordable housing available to those income levels. Besides homelessness, the crisis also manifests quietly in early-morning commuters driving daily from far beyond the Bay Area, young students sleeping in cars, and seniors stuck in single-family homes they can no longer maintain.

Retrofitting The Suburbs

And yet Cupertino contains the historical seeds of a very different vision: of densification, mixed-use growth, and alternative transportation. The Heart of the City specific plan, which found its genesis in the 1990s, prescribes a walkable commercial corridor on Stevens Creek Boulevard with a strong sense of identity. Stevens Creek, a six-lane road of shopping centers, office parks, and the dead Vallco Mall, runs through Cupertino and connects it to Downtown San Jose. Because it never had a pre-war downtown like its neighbors, Cupertino has long sought a more attractive and cohesive commercial center. As a result, street-facing shops, mixed-use developments and dense housing already coexist with strip malls and parking lots on Stevens Creek. Families, students, seniors and Apple employees walk along the road’s buffered and landscaped sidewalks. Cupertino’s current bicycle infrastructure plan calls for a citywide network of dedicated trails and protected bike lanes along the whole Stevens Creek corridor. The first mile-long stretch opened in early 2021, separating bicyclists from fast-moving traffic with concrete barriers. Originally a streetcar corridor until the 1930s, Stevens Creek already hosts one of the county’s busiest bus routes, sped up by a transit signal priority system. Political controversy aside, Cupertino’s commercial core already seems primed for urban growth.

To gain more historical background, I spoke with Richard Lowenthal, who served on the Cupertino City Council from 1999 to 2007. A former tech entrepreneur, he sold off a startup and devoted his attention to non-profit work and public service. Lowenthal described his early attempts to promote pedestrian-friendly development on Stevens Creek Boulevard in the early 2000s. For example, he insisted that a proposed cafe face the street and leave the parking in the back. This would encourage customers to not only walk to the cafe but also walk to nearby shops afterward. “We shouldn’t be a highway town. Good design is ‘park once, shop twice,’” he says. Such design conformed with the Heart of the City plan, which aimed to improve pedestrian connections. Still, the proposal attracted opposition from residents who feared that there would be inadequate and inconvenient parking.

“We shouldn’t be a highway town. Good design is ‘park once, shop twice.”

Richard Lowenthal, formerly a member of the Cupertino City Council (1997-2007), to the author

We met inside that very same cafe, almost twenty years after it was built. Visitors of all ages filled the establishment, from high school students to parents and seniors. On a sunny California winter day, even the sidewalk tables were packed. It’s hard to imagine that this could have ever been controversial. Lowenthal points to an empty strip mall across from Stevens Creek tucked behind a sea of parking lots to contrast with the street-facing cafe. Although the Heart of the City plan allows some housing as a supportive use for commercial developments, it has strict three-story height limits and does not envision Stevens Creek as a true mixed-use district. Visitors are still expected to drive. Shifting from a well-landscaped shopping area to an urban neighborhood will require further improvements in walking, biking, and public transportation options.

In addition to Cupertino’s growing bike network, transit will be an essential ingredient to developing an urban center. The Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA) operates local bus and light rail service. Most of Cupertino’s arterial roads are covered by buses but they are slow and lightly patronized, serving mainly as a safety net for students, senior citizens, and low-income commuters. Although Stevens Creek Boulevard is one of VTA’s busiest corridors and boasts buses running up to every eight minutes, transit remains underutilized in Cupertino and across Santa Clara County.

Despite these flaws, VTA emerged from COVID in better financial shape than its Bay Area peers. It has restored almost all of its pre-pandemic service and over three-quarters of its ridership. The agency is now turning its attention to future expansion, launching the Visionary Network initiative to plan a major increase in transit service.

Stevens Creek’s strategic location has also been eyed for a rapid transit corridor study led by the city of San Jose. The cities on the corridor, including Cupertino, hope to greatly improve transit connections with Downtown San Jose and the San Jose International Airport.

Monica Mallon, who writes about transportation issues in the Bay Area and heads the local transit advocacy campaign Turnout4Transit, sees emerging opportunities to boost transit service in Cupertino. She supports the Stevens Creek rapid transit study and believes that cooperation between Cupertino and San Jose will be vital in securing funding for such a capital-intensive project. In the near-term, the city could modernize its transit signal priority and street design to further increase bus speeds. Cupertino could also explore direct partnerships with VTA – contracting with the agency to run special routes. “It’s not an option that many people know about,” says Mallon. She cites the example of the Santa Clara Valley Medical Center Shuttle, a new service connecting the county’s public hospital with San Jose’s main railway station. By seeking regional partnerships and collaborating on VTA’s Visionary Network plan, Cupertino can offer useful and credible alternatives to driving.

Crabgrass frontlines

Despite the city’s prosperity, the main shopping mall in Cupertino, Vallco Fashion Park, has long been plagued by empty storefronts and joins the nationwide ranks of dying malls. A controversial attempt to redevelop the declining Vallco mall and build affordable housing illustrates the barriers to housing development in Cupertino.

In 2014 Sand Hill Properties, the owner of the Vallco site, proposed a new mixed-use town center with over two thousand housing units, retail spaces, and offices. Cupertino created a Vallco Specific Plan and negotiated a host of community benefits with the developer, based on community feedback. However, the Vallco proposal proved to be divisive and sparked strong opposition to housing development on the site. A community group named Better Cupertino emerged as the face of the opposition, suing the city and running its own candidates for city council. Better Cupertino-endorsed candidates won control of the council in 2018 and overturned the Vallco Specific Plan.

Ending the Vallco Specific Plan did not end Vallco, however. Sand Hill Properties had put up an alternative project with 2,402 housing units, of which 50% were reserved for low-income residents. This allowed them to take advantage of SB35, a 2018 state law requiring approval of developments with a certain amount of affordable housing. With the Vallco Specific Plan off the table, the SB35 plan moved forward with no public process or community benefits. Despite this state-mandated approval, progress on Vallco remains glacial. Most of the mall has been demolished but construction has not yet begun, leaving a fenced-off empty lot in the middle of the affluent city.

Beyond socioeconomic disparities and alleged impacts on property values, former councilmember Lowenthal also attributes the opposition to housing to the deep-seeded fears that change can invoke. “I think NIMBYism is a very primal problem. It’s a 20,000 year old problem of people protecting their cave,” says Lowenthal. Beginning with early redevelopment attempts in the mid 2000s, Vallco and development in general became increasingly controversial, with raucous city council meetings continuing well after midnight and elections characterized by vicious mudslinging.

Alon Levy, a fellow at the NYU Marron Institute of Urban Management notes, “Individual rich people can be virtuous. Rich communities never are.” Those who would benefit most from affordable housing in Cupertino aren’t able to vote for it because they simply can’t afford to live there. Without any consequences, municipal leaders including those in Cupertino, have long sidestepped housing targets and blocked development, contributing to the statewide crisis.

Cupertino’s leadership navigates a complicated landscape of state housing requirements. While the RHNA process has existed since the 1970s, enforcement of housing targets had been hands-off until the late 2010s. Municipal leaders often lobbied Sacramento to reduce their RHNA targets, selected sites in their Housing Elements that they knew would not be feasibly built, or refused to select sites that would be ripe for development. This complex process is typical of California’s well-intentioned but byzantine regulations. As a result, state housing officials lacked the capacity and political will to do much more than rubber-stamp these Housing Elements.

As the housing crisis worsens, however, California is now demanding more affordable housing in cities that have long resisted. SB35 was just one of many state laws designed to compel municipalities to approve affordable housing. Cupertino councilmember JR Fruen points to recent legislation that strengthened existing housing laws, simplified the RHNA needs calculation, increased penalties for non-compliance, expedited approvals, and upzoned commercial and residential areas. Statewide elected leaders have stepped up involvement, with Governor Gavin Newsom sweeping into office on promises to tackle the housing crisis and Attorney General Rob Bonta signaling his readiness to enforce housing laws against scofflaw cities. In the worst case scenario, Fruen argues, the courts would be able and willing to enforce the law by drafting a compliant Housing Element for Cupertino – this time with no local control. Suddenly, the Housing Element has gone from a paper-pushing exercise to a vital plan for every city’s future.

Cupertino, like most Bay Area cities, missed the January 31st deadline for adopting a state-approved Housing Element. Besides exposing it to fines and withdrawal of state infrastructure funding, the lack of a compliant Housing Element means that the so-called Builder’s Remedy goes into effect. This provision of California law means that any development with a certain amount of below market rate housing must be automatically approved, regardless of what the city’s zoning code allows.

Although legally untested, there is good reason to believe the Builder’s Remedy has teeth. Wealthy Southern California suburbs and beach towns have seen a spate of dense affordable housing proposals under the auspices of the Builder’s Remedy. Such projects have begun to trickle into other Bay Area cities as well. Councilmember Fruen believes that the provision will survive any legal challenges to reshape Cupertino’s landscape. Developers will be more likely to propose new housing, knowing that they can get something built no matter what thanks to the Builder’s Remedy.

A vision for the future

Change seems to be on the way, however. The 2022 midterm elections ended Better Cupertino’s control of the city council. Newly elected councilmembers JR Fruen and Sheila Mohan joined Councilmember Hung Wei in forming a 3-2 majority endorsed by Cupertino For All and amenable to dense affordable housing. The new council proceeded to elect Councilmember Wei as mayor. In her first speech as mayor, she promised to take a broad view of her constituents: not only existing residents but also future residents and the city’s tens of thousands of daytime commuters.

Hung Wei, a former school board trustee, got her political start supporting teachers, custodians, and other school employees who could not afford to live in the community they served. As a longtime resident and community volunteer, she hopes to build consensus around creating more affordable housing and thinking long term. “We need to think about what we can do for future residents and serve those who work in the city. We cannot plan Cupertino just for the current residents. We need courageous leadership to look for the future,” she said in an interview. A cornerstone of her 2020 election campaign was to create a variety of housing options beyond expensive single family homes.

I also spoke with JR Fruen to understand the freshman councilmember’s perspective. At 43, he is positively young compared to the Baby Boomers who typically dominate local government. He speaks animatedly about the intricacies of California housing laws the way only an attorney could. A third-generation Cupertino resident, Fruen became interested in local politics when he graduated college into the dot-com bust economy of 2002 and encountered the lack of affordable housing options even for young professionals. At the height of the Vallco controversy, he founded Cupertino For All to advocate for more housing growth and tenant protections. The organization quickly grew and consolidated support from like-minded residents and local leaders.

In small local elections with limited public information and low turnout, Fruen cautions against reading too much into the results. But he believes that a worsening housing crisis and Cupertino For All’s advocacy have shifted public opinion on housing. “Now it’s no longer ‘those people’ and now it’s someone I know,” he says of changing attitudes. “New housing could be occupied by my kid or my parent who’s downsizing.”

Fruen … believes that a worsening housing crisis and Cupertino For All’s advocacy have shifted public opinion on housing. “Now it’s no longer ‘those people’ and now it’s someone I know.”

Between market demand, state regulations, and pressure from affordable housing activists, it is harder to sustain blanket resistance to growth. Wei, the new mayor, says that residents have seen new housing sprout in neighboring communities. Residents would prefer to move past the dysfunctional brawls over the ruins of Vallco to at least manage development on their terms. Crediting these shifts with the new council’s victory, she hopes to meet and exceed Cupertino’s affordable housing targets through better planning and negotiations with developers.

All the public officials and advocates I spoke with agreed that the council needed to ratify a good-faith Housing Element, not only to satisfy state law but also promote a more dynamic, affordable, and sustainable city. The Cupertino For All-backed council has converged on a vision of building high-density housing in the city’s main commercial center on Stevens Creek Boulevard. By mixing housing and commercial amenities in walking distance and building near transit, housing advocates believe that Cupertino can create more affordable housing options and an attractive business district while reducing its longtime dependency on the automobile.

To Mayor Wei, the housing and transportation issues are inseparable. She is an enthusiastic supporter of the rapid transit study, even if it could mean removing a car lane from Stevens Creek. “Don’t we want people to shift from driving alone?” Fast and frequent transit is not simply a competitive amenity, but essential to unlocking more housing development and meeting the city’s affordable housing goals.

She points to multiple examples of past affordable housing developments on the corridor where builders did not take advantage of density bonuses allowed by state law, citing onerous minimum parking requirements as the culprit. A general plan amendment, she says, will be necessary to reduce parking requirements and rezone Stevens Creek for more housing. “It’s going to be controversial.” In May 2023, the state is expected to respond to Cupertino’s proposed Housing Element. With state approval looking unlikely, Cupertino’s leadership must take this chance to revise the Housing Element, implement new policies, and lay the foundation for a positive vision for the city.

The city in the suburb

The question remains on how the housing crisis will affect Cupertino’s single-family neighborhoods, which make up most of the city’s area. California’s SB9 bill, which allowed up to four units on lots zoned for single-family housing, was a lightning rod of controversy when Governor Newsom signed it in 2021. Despite the sound and fury, SB9 has not catalyzed the housing development that both supporters and critics expected. One of the culprits: strict municipal ordinances that make SB9 as hard as possible to use. Single-family zoning, long enshrined in zoning codes across the country, is politically and economically tough to crack. Instead, vast strip malls and parking lots can be developed much more cost effectively and with less controversy.

Single-family areas are expected to play a small role in Cupertino’s housing plans. Fruen believes that with or without SB9, Cupertino could still encourage neighborhood growth by offering pre-approved design templates and by allowing separate ownership of units on the same parcel of land. He envisions that Cupertino’s multi-generational families could grow and stay by building multiple small houses on the same lot. Wei discussed a few neighborhood sites in the Housing Element where property owners have expressed interest in small townhomes and apartment buildings, as well as working with faith leaders to build housing on oversized church parking lots. She also believes that the city should encourage the construction of accessory dwelling units and even explore a home-sharing program connecting empty-nested homeowners with young people hoping to live in Cupertino. Finally, she wants to loosen regulations like parking and setback requirements that discourage infill development: “Do you want to have two more feet of space or for your neighbors to be able to stay in Cupertino?”

Still, the focus remains on redeveloping commercial areas while handling single-family neighborhoods with a light touch. Sixty percent of Cupertino’s residents are homeowners, and they tend to be older, wealthier, and more politically active. Despite Cupertino For All’s recent victory, continued success is far from certain. Politically-connected homeowners could revolt once they start feeling the impact of increased development. “We are still a divided city,” says Wei. She hopes to build consensus around adding more affordable housing through negotiation with developers, rather than reflexively opposing new projects or leaning on state mandates. “I think people have a right to be mad when the state mandates a lot of things. And state laws are harder and more expensive for developers to use.” A well-considered plan focusing development away from single-family neighborhoods and with the goal of negotiating community benefits from developers could defuse opposition and bring community members, even former hardliners, together to support housing growth.

Another challenge will come from integrating the “new” and the “old” Cupertino: dense transit-oriented apartments in the core surrounded by car-dependent subdivisions with minor tweaks. For instance, it’s an open question as to how pedestrian-friendly a 120 foot roadway can really be (I suspect “not very”). Stevens Creek Boulevard was designed to move high traffic volumes through Cupertino. It has very few intersections with neighborhood streets, which keeps traffic flowing and away from single-family residences. But it greatly limits walking and biking paths from sprawling subdivisions to the transit stations and urban neighborhoods that would lie on the corridor.

Although the suburban pattern enshrined in Cupertino’s general plan is designed to “protect” single-family neighborhoods from commercial areas, this goal is fundamentally incompatible with the vision of a truly walkable and mixed-use community. Future leaders will have to navigate this contradiction and find the balance between creating an inclusive and accessible city while placating wealthy and influential homeowners.

Cupertino has many advantages over other American suburbs due to its affluence and position in the high-demand and strategically important Bay Area. It can attract housing development and secure funding for capital-intensive transit projects, making it a unique laboratory for exploring the future of suburban growth. Although development struggles in major cities dominate the headlines, America remains a stubbornly suburban nation. What happens here can offer lessons for the suburbs in which a majority of Americans live.

The haunted house of California’s housing planning process also serves as a valuable lesson for other expensive states hoping to make a dent in the housing crisis. New York governor Kathy Hochul seems to have taken the right cues. Rather than play with complex needs calculations, her recently-announced housing compact simply calls for a flat 3% housing growth target every three years in New York City’s community districts and suburbs – with incentives for permitting below market rate units. After years of dawdling, the scale of the housing crisis has finally thrown state legislators around the country into action.

A comprehensive process that offers incentives for cooperation and wields punishments for non-compliance could make the most expensive metro areas more affordable for poor and working class families. But these are still the early stages. Progress will depend not only on overcoming resistance from wealthy homeowners but also on offering an affirmative vision for a cleaner, friendlier, and more integrated future for all.

(This article was originally published many moons ago in The Wagner Planner, the planning publication of New York University, and is reprinted with permission).