Gentrification: Inevitable In Detroit, Still Not Actually Our Biggest Problem

Have you heard the good news? Detroit’s coming back! New stadia, high-density development, a 3.3 mile streetcar line, and the fact that everyone in the city of New York is suddenly super excited about The Next Brooklyn, all of this heralded by angels draped in gold Tyvek and playing trumpets made of scrap copper, have prompted increasingly heated debates over the dreaded ‘G’ word. Is it happening here? More broadly, is gentrification even possible in a city that has such low housing prices and such high rates of vacancy? If it’s happening, is it the biggest threat to the stability of housing in the city?

Yes, yes, and… no, no, probably not, not by a long shot. Gentrification is inevitable in central Detroit as a product of a lack of housing supply, if nothing else, and that lack of supply is, in turn, a product of lethargic capital markets. However, we can try to solve questions about equitability while solving problems of capital. That’s the good news. The bad news? Gentrification is dwarfed by a more insidious and farther-reaching problem that gets missed because it isn’t happening in the urban core.

Detroit in the Era of Austerity and the Wealth Gap

Detroit’s trumpeted rebirth has been surrounded by complex questions on the national stage about cities themselves and the people in them– most generally, how development can be equitable as the wealth gap continues a many-year trend of widening; questions of black erasure, at a time when we are asking whether everyone really does believe that Black Lives do Matter (definitely not everyone, by the way), and racial and economic justice, when we have a presidential administration that explicitly said it wanted to ban Muslims from the country– and then tried to, that appointed a man to run HUD who believes that poor people are poor because they’re lazy, and among whose sole nods to diversity is that they allows Paris Motherfucking Dennard to open his mouth ever.

It’s not necessarily a climate conducive to pluralistic dialogue. But we’re also trying to have that dialogue during the austerity era of city-building: Detroit has just emerged from a devastating municipal bankruptcy, the state of Michigan gives billions in handouts to big business while cutting funding to programs that help workers and low-income families, and so, well, stuff isn’t easy. On the bright side, especially given Detroit’s ascension to national coolness, we are afforded the spotlight to do it, not to mention some of the best and the brightest urban planners and thinkers who are committed to solving this problem equitably. I mean, maybe.

When I think about perception, I think about the questions I’ve gotten over the years in the following progression: What was first, “Oh, my God, Detroit! Do you own a gun?!” or “Do you have running water?” became, first, from the intelligentsia, “Oh, my, so many interesting things are going on in Detroit! I heard this great piece on NPR about this musician, I think his name is Jack White!” (Yes, I’ve heard of him.) or, frequently, “Detroit! Dude! Do you, like, live in a $500 house [like Drew Philp]? I read this article… [or it might have been this one]…”

It’s the same kind of snark I so desperately hope San Franciscans appreciate when I, upon finding out where they live, tell them that “I hear that the startup scene is lovely this time of year.”

Expropriation: Not A Virtuous Free Market Kind Of Thing

I don’t live in a $500 house, and I have never met Drew Philp. I pay affordable rent for a house that was renovated about 15 years ago, before Detroit was, you know, the Next Brooklyn. That doesn’t mean that I don’t live in perpetual fear that my landlord will kick us out to sell the house for, say, $200,000 cash (let’s say, 130-150% of the average regional home price) which is entirely conceivable, given some recent Corktown sales, and the sort of thing that happens in the real estate bubble of the 7.2. When I lived in the not up-and-coming, still-today-quite-abandoned Milwaukee Junction, a certain major property owner in the neighbourhood who shall remain nameless (a.k.a. some folks I did some consulting work for and in whose property I lived) told me and my roommate that we’d have to leave unless we wanted to pay $2700 a month in rent. (That was about $2 a foot– so, prices like Philly or Miami, but in a neighbourhood that lacked street lights and recycling pickup and snow plowing. But where artisans were making picture frames out of reclaimed wood, and down the street from the Shinola factory, so, you know, trade-offs.)

In the quest to push rents toward $1 a square foot, some real estate developers embrace the mentality that we must actually double the value for the rest of the market to catch up to where it “needs” to be. (I’m being a bit facetious here– especially younger real estate and private equity guys always take this perverted approach to what ‘should’ be based on what they read in a book in B-school or what they learned in a house-flipping seminar.) Of course, developers are getting takers at $2 a square foot– just not within 15 minutes. (In contrast, at Southwest, we were typically able to accept an offer on a house within days of listing– closing it was another matter, but more on that later.)

Gentrification is a hotly contested term, and few really agree on what it means, or whether it’s bad. Merriam-Webster goes so far as to include “displacement” as a frequent product of the new investment that it involves. (The Corporate Landlord, of Granite Countertops, Stainless Appliances, And Jacked Up Rents.) Some people just use it to mean “wealthier people moving into a neighbourhood, fixing up the old houses.” (The Benign, Well-Meaning, Double-Income No Kids White Folk With Tattoos, A Large Dog, And Good Jobs.) When the Michigan Daily recently weighed in, they defined the “process which low-income communities are renovated and rebuilt, attracting young professionals but also usually driving up real estate prices and relocating pre-existing residents and businesses.” Okay. It is generally acknowledged by both elitist free marketeers and the most rabid social justice warriors alike that there are more intentional ways of doing things that end up working out better for everyone, given the inevitability that markets are real, people do respond to markets, and the trend is that wealthy people will gravitate toward lower cost areas.

So, new investment resulting in expropriation is a bad thing, right? Market urbanist types will often abandon their “live and let live” mentality when it comes to upping prices in real estate, saying that the prices should be as high as the market can bear, and if people get kicked out of housing, that’s just the way the cookie crumbles. (Oh, sorrow! The housing supply is just too low! What ever could have been done?!) But while loath to admit that for-profit business has any culpability in bad things that go down ever, they are wont to point out that municipal administration can proactively or disastrously guide development, such as this example of how Dallas planners forced some bogus zoning overlay to overtly kick out people they didn’t want. They also argue that encouraging upzoning and densification increase supply and therefore decreases the likelihood that rents will go up based on basic supply and demand.

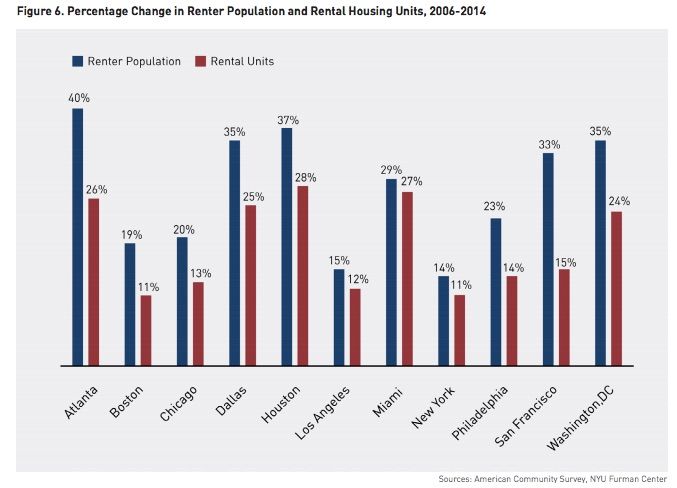

This may hold true, considered in the macro perspective– the whole market. It may also not, especially if it’s not spread out, and if demand for rentals remains steady or increases as it has been while supply of funding for affordable units does not increase:

A perceptual problem here is the reality that no one even lives in the 7.2. We consider it the center of the city because, well, it is the geographic core of the city, but the density of it is basically like a somewhat kinda sorta dense suburb. Job density is high because of your General Motors, your Quicken, your State of Michigan in New Center, your Shinola factory cranking out shiny things, or your Henry Ford Hospital, but for every four story apartment building you have a giant parking lot. Royal Oak has a higher population density than the 7.2. Wyandotte has a higher population density than the 7.2. St. Clair Freaking Shores, with its boats and its ranch homes and its racist boat people, has a higher population density than the 7.2. Hamtramck has about three times the density of the 7.2. And yet the 7.2 is where the expropriation is happening, right?

| 2010 pop. rank |

Municipality | County | 2010 pop. | Area | Density | Classification |

| 83 | Hamtramck | Wayne | 22,423 | 2.09 | 10728.71 | Urban |

| 45 | Lincoln Park | Wayne | 38,144 | 5.89 | 6476.06 | Inner Ring |

| 116 | Hazel Park | Oakland | 16,422 | 2.82 | 5823.40 | Inner Ring |

| 24 | St. Clair Shores | Macomb | 59,715 | 11.62 | 5138.98 | Inner Ring |

| 99 | Ferndale | Oakland | 19,900 | 3.88 | 5128.87 | Inner Ring |

| 26 | Dearborn Heights | Wayne | 57,774 | 11.74 | 4921.12 | Inner Ring |

| 1 | Detroit | Wayne | 677,116 | 138.75 | 4880.12 | Urban |

| 27 | Royal Oak | Oakland | 57,236 | 11.79 | 4854.62 | Inner Ring |

| 35 | Roseville | Macomb | 47,299 | 9.83 | 4811.70 | Inner Ring |

| 34 | Redford* | Wayne | 48,362 | 11.2 | 4318.04 | Inner Ring |

When we talk about rising rents in rental housing alone, probably, yes. We don’t have great data on it, just anecdotal evidence and ways to track rising rents, generally. There isn’t a database of people who got kicked out of their apartments. It’s not just long-time residents but also companies that made Greater Downtown a place you wanted to hang out and shop– Goodwell’s Natural Food, for example, or Café con Leche on Clark Park in Southwest Detroit. Some affordable units are included along with the advent of $5 coffee and “urban cabins.”, for example ,and attempts to keep Midtowners in Midtown are even being funded through basically cash grants from foundations. (One of those moments where I watch something happening and just say, “Huh,” because weird stuff happens in Detroit.)

The Equitable City: Densification Without Expropriation

I’m going to propose something radical for my Wharton and Ross friends who worship at the Holy Shrine of the Divine Market- and that’s that every citizen has the right to live without fear of eviction or expropriation. Does that mean that I should be able to lie about my income on a rental application and then not pay rent? Does that mean that I should be able to conduct criminal business inside my house and live there without consequence? Rent control forever and ever? I mean, no– we need to have a functional society where people take responsibility for things and where markets are allowed to function properly (I don’t even really believe in rent control, but that’s another article). But people should also have the right to live productive lives, enjoy the communities they live in, and enjoy access to the same market information.

Eviction and expropriation purely in the name of profit, the central theme of Matt Desmond’s recent book making the rounds in discussions among urban planners and mere mortals, have profound effects on the health of individuals, families, and entire communities. It is an ugly, horrible thing, and no one should ever have to go through it, full stop.

Back to my previous point about perception from outside the Detroit bubble, one of the biggest questions I get (aside from “but the schools,” which is akin, in my opinion, to “but her e-mails“):

“High prices, wow! But isn’t there a lot of vacant housing in Detroit?”

Well, there are a lot of vacant structures, but vacant livable housing? No. LOVELAND estimates that about 19% of the structures in Detroit are vacant, and about 31% of the parcels in Detroit don’t have structures on them. Since there’s no way to accurately estimate occupancy rates of livable structures in a city whose understaffed building department would probably lack the political will to aggressively enforce occupancy ordinances even if they had the staff to (I was once all but chased out of the building department when I requested a certificate of occupancy), I can only go off anecdotal evidence from working in a few portfolios of affordable and market rate housing– but the gist of it is that the effective occupancy rate in livable units is near 100% in much of the city. Southwest Housing, for example, has a weeks-long, sometimes months-long waiting list for one of its nearly 700 rental units.

Detroit is hardly bucking the national trend, as indicated in this graph from NYU’s Furman Center which shows that developers aren’t building as fast as demand is increasing, among particularly millennials abandoning the suburban, white picket fences of their parents’ generation.

The Supply Problem vs. The Capital Problem

So, vacancy is low, demand is high, and development is sort of happening. I will refer to another well-intentioned, though nonetheless misguided, question that I often hear:

“How can we have homeless people when there are so many vacant homes?!”

Yeah, I mean, I get what you’re going for there. I really do. We can’t house homeless people in vacant housing because buildings are really exorbitant to renovate, and because you can’t finance based on the possibility that people might end up being able to afford rent, and because in the Rick Snyder And Donald Trump Austerity Era, we don’t have easy access to affordable funding streams to provide either grants or affordable capital to build things (bruh, we done spent all that money on tax breaks for wealthy people and it shall trickle down like the purest April rain through a badly-designed building envelope).

Real estate isn’t like selling smartphone apps or widgets—you plop a few hundred grand down and suddenly you have a many-ton widget that, if all goes well, will be happily functioning for, well, literally centuries. Of course, if you screw up, your many-ton widget collects dust– and, say, spendy blight tickets. This is why debt, perhaps the most misunderstood subject involving money in America today, exists, and why debt and capital are critical to the real estate equation.

Downtown office space in Detroit is tight, with JLL noting that vacancy rates dropped in 2016 below 10% for the first time in, well, a long time. Despite new construction like the planned development of the Hudson’s site on Woodward (development á la “needless and expensive demolition of an iconic, monumental building to build another needlessly expensive, iconic, monumental building”), residential construction is taking its sweet time.

Though the Land Bank renovation biz is reasonably brisk, it’s not happening fast enough: when I left Southwest Solutions, we were one of the largest if not the largest of the community partners and we weren’t even doing two dozen homes a year (more if you count REO flips and the weird deals we would do for foreclosure prevention and relocation assistance for the Delray/Gordie Howe Bridge, but still not a whole lot). There is a decreasing interest in one-off, scattered-site, single-family new builds, even though plenty of folks still misguidedly believe in the single-family development paradigm. Multifamily new builds are few and far between, and even the sum total of everything currently in the works, including the new modern boxy buildings in Indian Village, the neighbourhood construction sites that are Brush Park and Orleans Landing (not exactly affordable at $2 a foot, so, up to $3,315 a month), and a smattering of high-density one-off buildings on West Grand Blvd., Howard (downtown), and elsewhere– it takes a long time to design things and a long time to build them. I can damn near count them all on two hands, and I can probably name every single project in the city right now.

High-density development is tough in a city where lenders are having to rewrite the rulebook while developers realize that the single-family paradigm is probably dead. And, while I assume this will change a wee bit by 2020, the revised 7.2 report noted that in a few short years, downtown Detroit had actually lost population. I am 100% sure that higher-density development in the works will change this by 2020, but I don’t know how much.

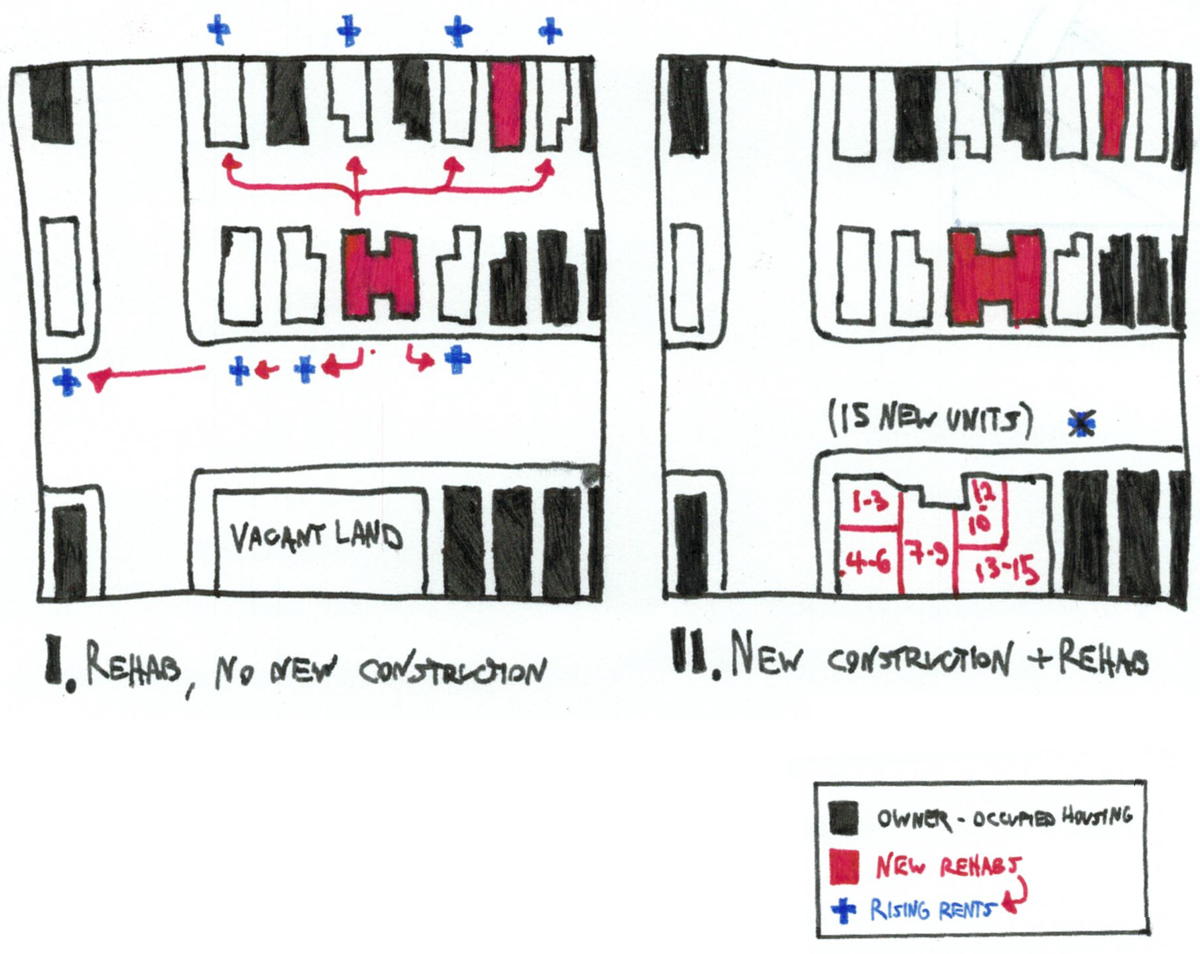

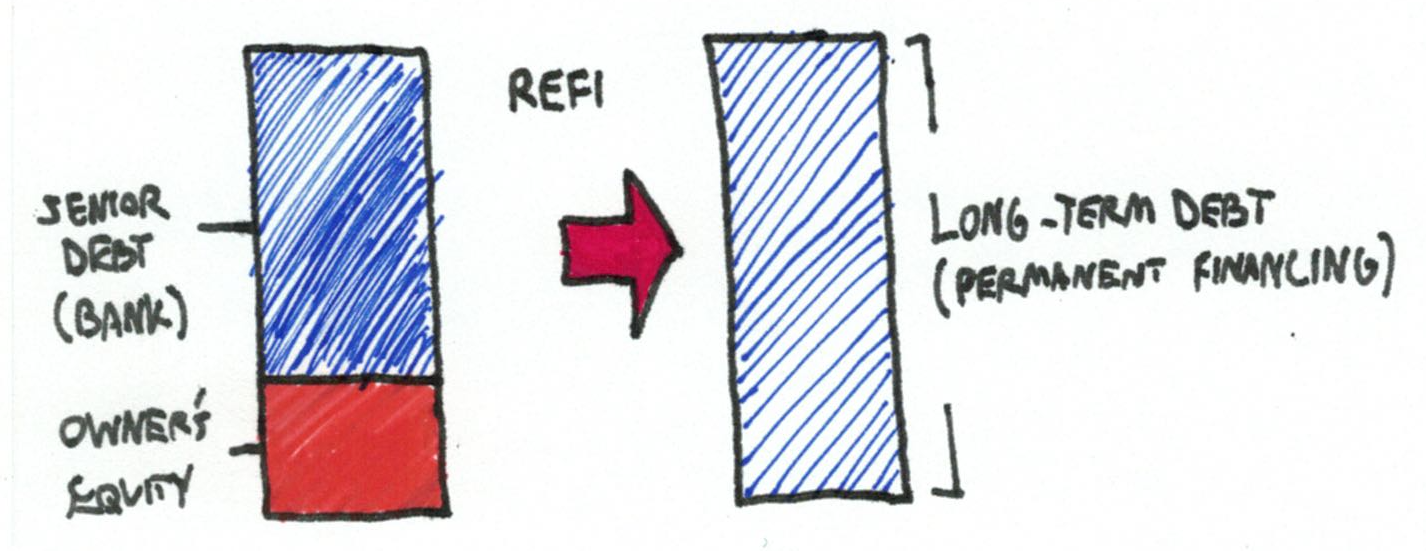

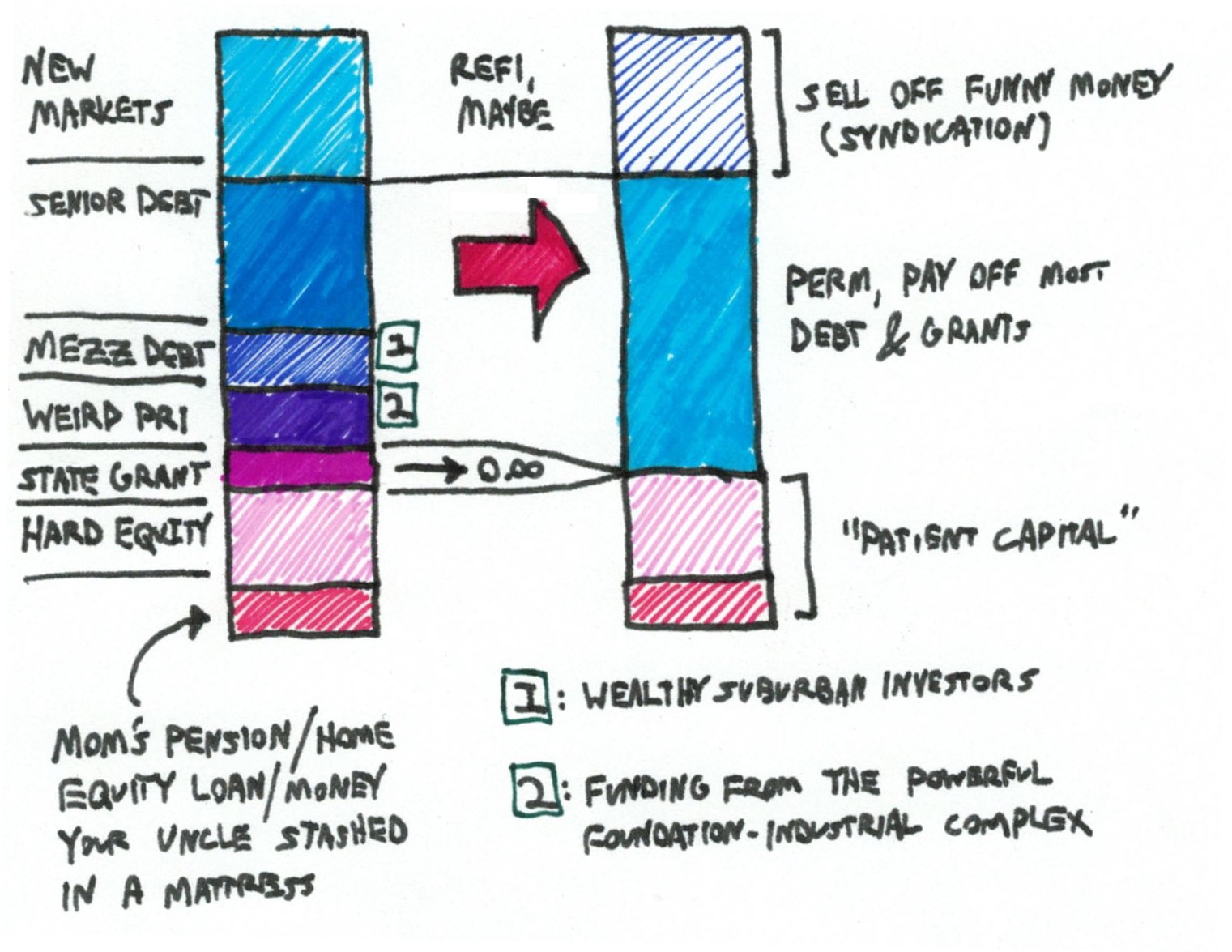

Below, an idealized illustration of how capital stacks work in normal cities in Detroit:

Yet in Detroit, the rulebook must be rewritten. What they used to call “redlining” (literally drawing red lines around black neighbourhoods to limit mortgage lending there) they now call “risk mitigation,” and that means that banks have a harder time lending. When banks won’t lend, more money has to come from investment capital, and investment capital can be as little as 25% more expensive or as much as 300% the cost of bank capital. Wealthy people like their money and they want to make more of it, especially when there is a chance that the project will fail and they will be left holding the bag.

There is some promise in the idea of changing the way we finance. After all, markets retool all the time based on a balance of regulation and the trendy scheme du jour, what I refer to as “cycles of capital innovation.” (Think the trust-antitrust cycle, the era of leveraged buyouts, or the era of venture capital.) Dan Gilbert built Quicken into its current empire as the multi-trillion dollar mortgage market shifted from banks selling mortgages to non-banks selling mortgages (that’s a whole different blog article).

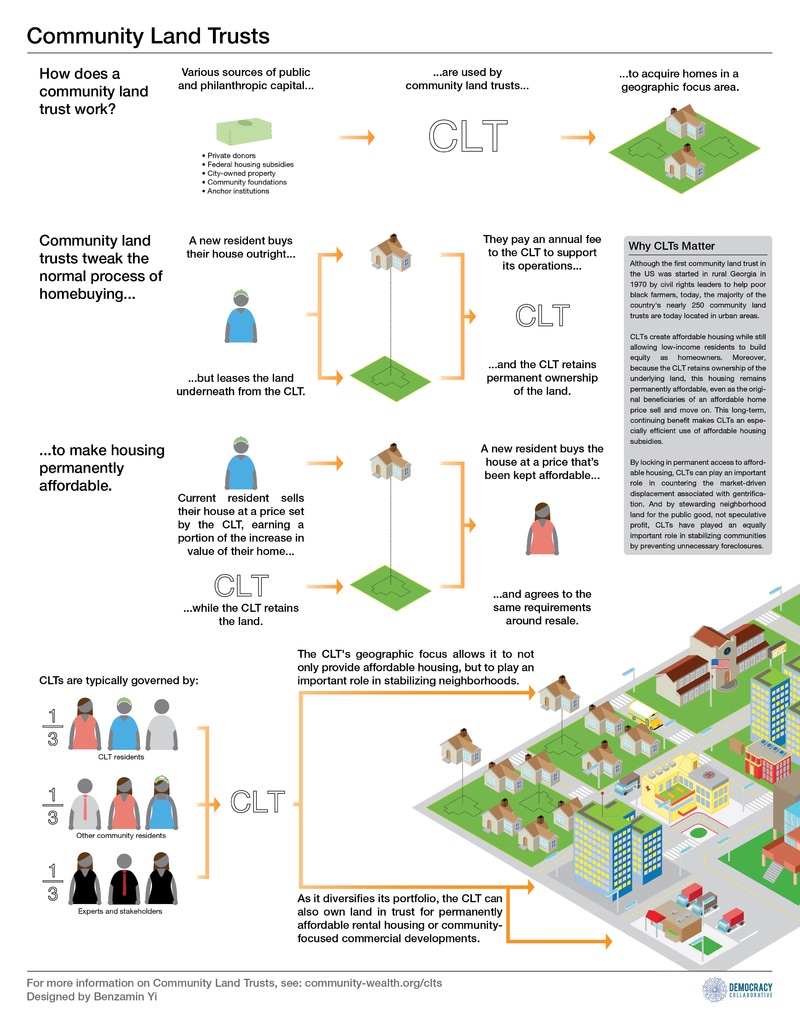

Strategies like crowd finance or the development of community land trusts show promise in terms of being able to structurally address the issues of social equity alongside capital, potentially helping us ameliorate gentrification while also providing capital to get stuff done. In the case of the former, however, I found that there was an extremely high learning curve, even among highly educated human beings, who don’t understand the difference between donating to a Kickstarter that will never deliver and investing money as equity or debt in a legally regulated instrument.

My only contention with the Detroit People’s Platform, a local platform for community land trust development, has always been that they are perhaps focused too much on the big picture of equitable community-building and focused too little on the technical and financial specificity that could actually help build the thing. If you want to talk about disruptive innovation, CLT’s are the way to do it.

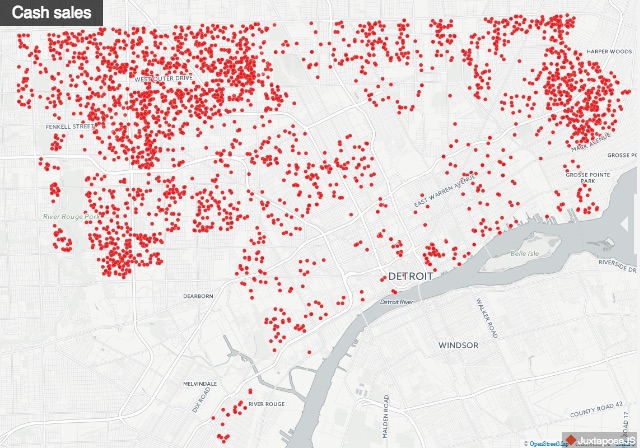

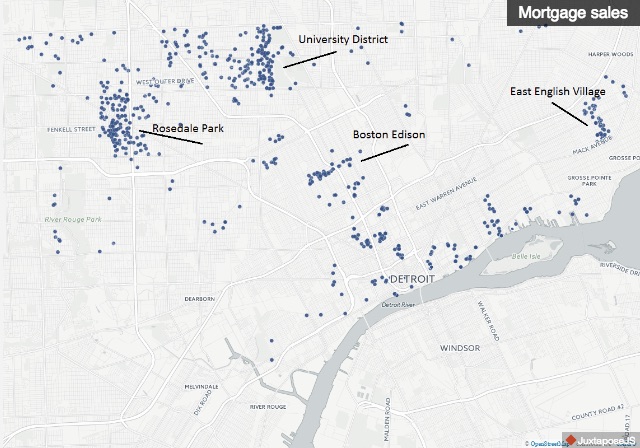

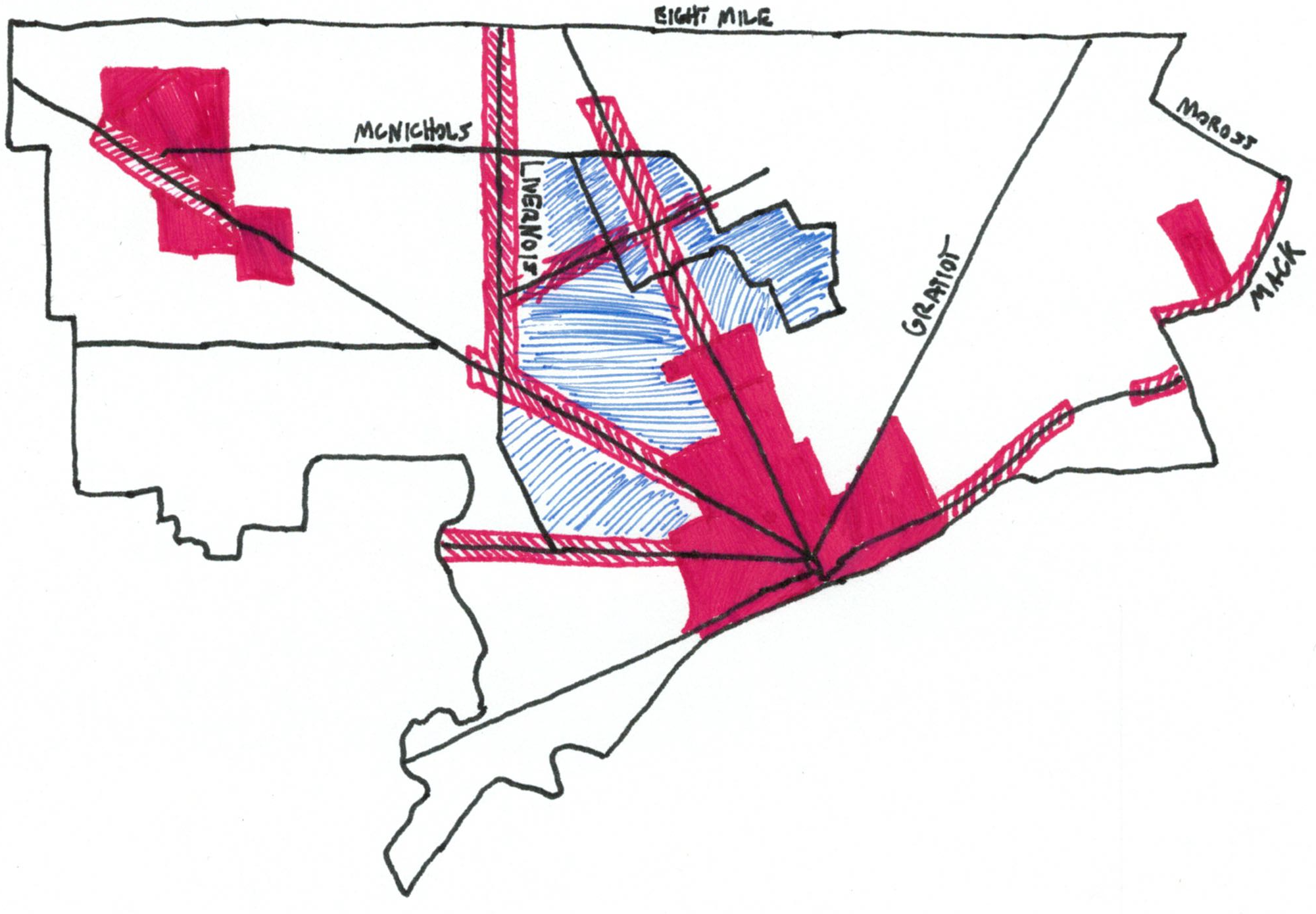

Mortgage finance is similarly broken, as indicated in these data from RealComp via Crain’s that show that mortgage lending is only really happening in the fairly stable neighbourhoods of East English Village, University District and Bagley, Grandmont-Rosedale, and Boston Edison.

Fixing the mortgage market would probably go a long way to stabilize neighbourhoods, as I witnessed working in Marygrove, where Chemical Bank (née Talmer) committed a lot of dollars in what I can safely say was a successful attempt at shoring up values.

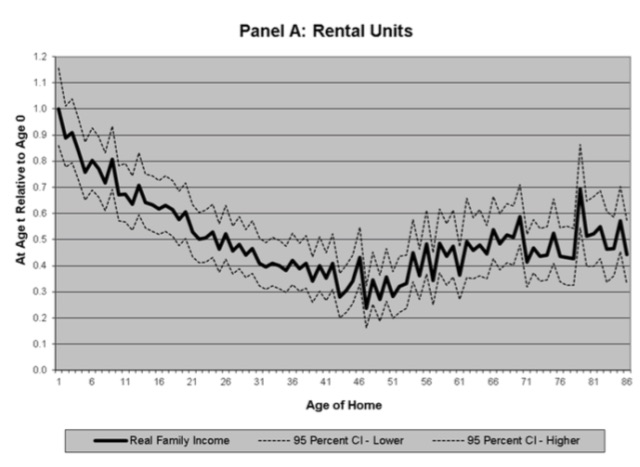

Fixing capital markets to fund higher-density development would, if coupled with a permissive city government, stabilize values– reduce a skyrocket to a gentle climb. It wouldn’t lower prices, though, without adding capital to fund the construction of specifically affordable units. For more on why not, check out this examination by City Observatory’s Joe Cortright, which doesn’t address the need for capital to fund affordable housing so much as it does the fact that new buildings are generally just more expensive and affordable ones have depreciated (simplification but I’ll take it):

So, we have plenty of information here that points to the reality that while the degree to which gentrification is resulting in expropriation within the 7.2 is somewhat unclear, that expropriation seems inevitable (the Duggan administration’s new requirements for affordable units will ideally encourage developers to drive up density and preserve affordable rents). But addressing the supply of housing units and capital, even aggressively within this geography, won’t fix the foreclosure crisis or the dearth of accessible capital that is plaguing the rest of the city.

The 7.2 has about 35,000 people. Compare that number to 65,000 bank foreclosures in ten years, and compare that to more than 37,000 tax foreclosures in the past five alone (peaking in 2012 but not really decreasing much since then). So, you could literally double the rents in every apartment– from the brick warehouses of Eastern Market to the great architectural canyons downtown to the expansive western skies of Corktown, and you would still, at most, end up threatening with expropriation fewer people than are threatened with tax foreclosure every year. The Detroit news has also noted that these foreclosures don’t really actually result in anything other than a net loss to the municipality, which ends up having to manage resulting blight after the foreclosing party can’t sell the home. It’s not just banks, either– rampant speculation by investors has aggravated the problem, as University of Michigan Robert Kahn fellow and urban theorist Eric Seymour has noted.

So, there’s your “free” market at work, but we need to recognize that it’s really not a free market, it’s a market that tolerates heavy subsidy to some and excludes others.

I don’t believe in trickle-down economics, but I do believe in radiate-out economics, easy in a city defined well by its axial, high-speed, ultra-low-density boulevards– if it means that upping density in the urban core will not only stabilize housing prices over the long term but also effect market-wide value increases that will actually benefit Detroit homeowners citywide and potentially put more tax revenue into the city to spend on novel, late 20th century amenities like street lights, schools, and recycling pickup.

The simplicity of it, though, is that we can’t talk about a Detroit renaissance at 4,200 people per square mile when that population density is barely holding steady. Fixing our capital systems is part of that. But we certainly can’t complain about gentrification without recognizing the damaging, widespread effects of a broken system of property tax assessment and resulting foreclosure. Addressing these issues in tandem will help ensure that we can help build a Detroit that not only offers a sustainable level of density but is also equitable for years to come.