Alleys: The Back Road To Sustainable Development

Take a stroll down an alley in Detroit and it’s apparent that these spaces are among the city’s most neglected. Even though my block, for example, only has four or five vacant housing units– a low percentage in a city whose highest density neighborhoods sometimes have double digit vacancy rates- the alley is just pretty gross. Trash is strewn about, agéd concrete spits aggregate at passersby, and weeds grow through cracks of pavement not touched since the age of Coleman The Greater. But alleys might be the back road to the kind of sustainable development that the city needs.

On a morning walk last fall, I marveled at just how overgrown the alley actually was. Dew glistened on leaves that hung low enough to touch the old bricks, invariably hand-laid more than a century ago. Invasive vines climbed chain link fences and grappled with native grasses and flowers in a veritable rainbow of ecology. I felt as though I had stumbled into Jeff Vandermeer’s Southern Reach— this fecund, alternate universe of sparkly things, nature reclaiming the city.

In this case, an alley could encompass the good, the bad, the ugly– and the opportunity for meaningful synthesis. It comprises the built environment by connecting houses and the walls that enclose their yards. It hosts public infrastructure– as a roadway, but also, usually, some sort of underground infrastructure- sewer lines in Detroit’s case.

It also can host green space.

Wild, I know. So, I started thinking about some ways we could address this. There’s been a lot of lip service paid to the idea of a green alley, which was implemented, to my knowledge, exactly twice– at the Green Garage in Midtown and between 2nd and Cass. Model D media charitably painted the issue as a revolution of sorts. But I don’t think a one-off, or two-off, solution counts as a revolution until it’s effectively scaled.

This article is about charting a path toward that scale.

I. ALLEY AS GREEN-BLUE INFRASTRUCTURE

Let’s first look at this question of general dilapidation and grossness. Trash pickup is easy and cheap. People usually litter either because 1) they’re just bad people, or 2) because they’re in part low-key bad people but, more significantly, are ultimately able to rationalize it with the fact that the space is already gross and broken, so, who cares? People are wont to continue to trash spaces that are already trashed.

What’s more expensive than picking up trash? Digging an entire alleyway up and rebuilding it from scratch. But not rocket science, certainly.

I used as an example my back alley because it’s what I know, but because it also evidences a number of design problems that will accompany most alley redesigns. Some lots have rear frontage. Some have cinder block walls with footings that may be intact or completely to’ up. We are lucky to have a hideous, though largely intact, cinder block wall. Neighbors have everything ranging from ratty old chain link fences (our front yard) to stately ones with powder-coated steel bars.

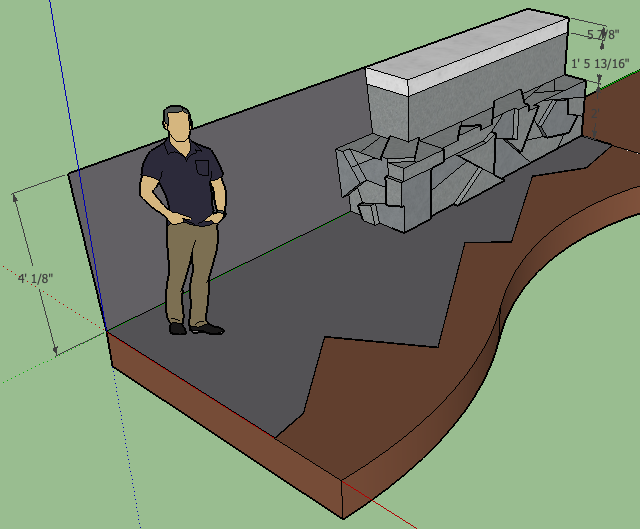

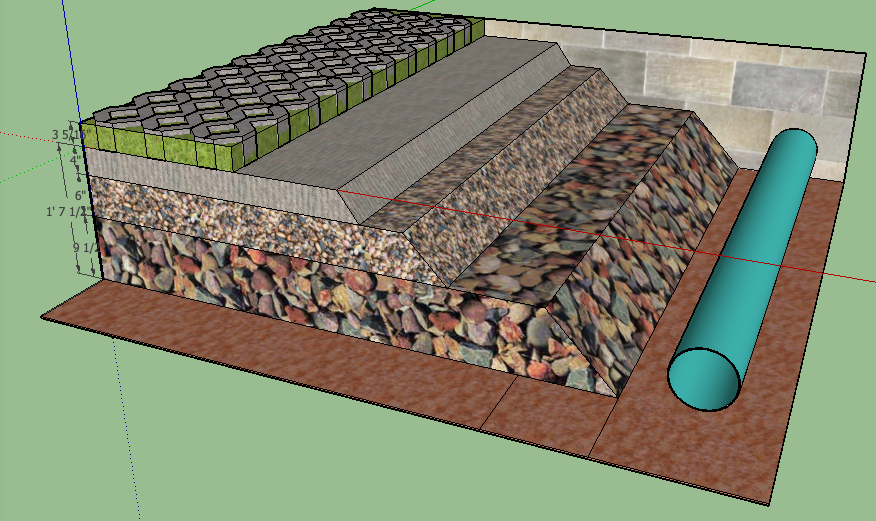

So, this diversity of borders makes pervious paving a bit trickier, but the principal costs here are really just digging up concrete and bringing in a shit ton of gravel. Various grades of gravel, too! My experimental and, I’m proud to say, thus far successful, backyard stormwater retention area swallowed up a few cubic yards of broken concrete as a base. And then six cubic yards of gravel. Finally, we then needed another cubic yard of marble chips on top of that. Except in one rainstorm that dumped about 30 mils of rain in less than a day, we have not gotten a drop of water in the basement. And even that was a serious improvement over what it had been before– that is, standing water in the basement any time there was more than a drizzle.

There are plenty of unresolved design questions, of course.

DRAINAGE

My stormwater retention installation doesn’t have a drain in it. If it ever fills up, I’m screwed. But I’m also confident that it won’t ever fill up, because it’s designed to hold something like a four-inch rainfall. Is a drain absolutely necessary? Water moves with a terribly minimal grade (thanks, gravity!). This is how virtually all municipal sewer systems work. And essentially why western civilization was able to advance by way of urban growth in the first place, right?

The problem with *not* having a drain is that a torrential rainfall will pool toward the lower-graded end of the pervious installation. An alley-sized installation would necessarily require a drain. But engineers often over-engineer systems, evidenced in the cases in which a street can be designed to drain surface water quite well, but very few cities have really cracked the code of expansive GSI built into the urban fabric itself. In other words, the idea of using the built environment to manage the retention, rather than the expulsion, of stormwater is fairly new– but our ability to move beyond simply smooshing a mixture of hot rocks and oil into an older mixture of hot rocks and oil has been limited by a lack of engineering creativity.

DURABILITY

Most of the looser pervious paving stones (like the “grass grate stones,” which have their own word in German, ‘Rasengittersteine,’ because of course they do) I’ve seen don’t look great after several years. Even the best so-called interlocking blocks separate from each other through freeze-thaw. Anecdotally, I’ve heard– though I have yet to see much evidence of this- that the biggest remedy to this is the ability to dig deeper to allow better settling of precipitation before it freezes.

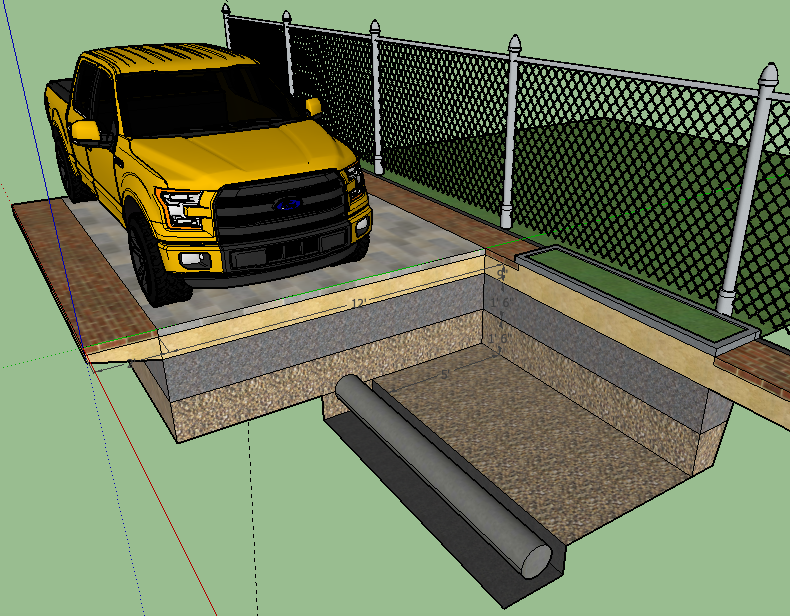

There’s no single standard for depth, though. There are different kinds of aggregate (the fancy name for “pebbles”). Many sources will say “a minimum of 8” with a hand-waving vagueness. When I spoke to folks from Unilock, they told me that I should plan on 19″ of depth for parkable space. 19″ deep isn’t spatially feasible with the skinny driveways of Detroit’s 1920’s neighborhoods, which were designed with the narrow Model T in mind. The Model T was only 56″ wide, while the Ford F250 Super Duty is about 80″.

Wear would be further antagonized by traffic from Detroit’s unrelenting love for ultra-heavy vehicles. As the F150 is the state animal of Michigan, sparkling white Cadillac Escalades are the flagship vehicle of southwest Detroit, and the neighborhood also features a wealth of stinky, semi truck traffic from the Moroun Clan and many more industrial interests around the neighborhood, any prospective permeable installations in Southwest Detroit have a lot of auto-traffic-related wear to look forward to. I’m hoping that someone has thought about this. Intuitively, tighter masonry installations with less pervious joints drain less water more slowly. But, as mentioned before, it’s as much about what’s underneath, not just what’s on top. Fortunately, semis don’t travel through alleys very often. But one would also think that they don’t drive down residential streets– and yet.

I’m not going to pretend I’m an expert on GSI. There’s been a lot of good stuff written, most of it recent, and most of it easily accessible online. In the course of writing this article, I found some great documentation from Wake County, North Carolina, Delaware‘s Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, and a wealth of information from manufacturers of paving products eager to get the word out about whatever new thing they’ve developed. Interestingly, permeable is not a new idea, but it’s a relatively new development in how we manage the built environment, so the market is expansive, fragmented, and evolving.

The City of Detroit’s DWSD has been notoriously difficult to pin down on the subject, and neither the city of Detroit nor the DWSD media department responded to multiple requests for information for this article. But they’re allegedly working on it.

I hope to highlight more stories about GSI. For me, I admit that much of the appeal is getting past the idea that the best way to build roads is to quite literally smoosh a hot mixture of tar and rocks into the ground.

II. ALLEY AS PRIME REAL ESTATE

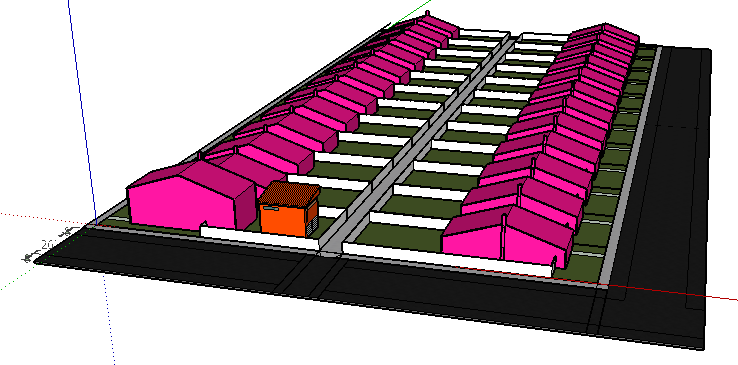

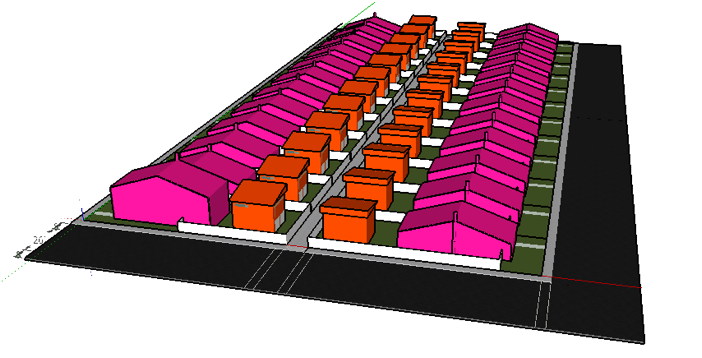

The second part of the alley conversation is about considering its liminal real estate. A few years ago, when I was managing a housing development program in Northwest Detroit, I came up with a plan to create Accessory Dwelling Units (ADU’s) as part of an idea of broadly boosting a local market. ADU’s are also known as “in-law suites” or the more pleasantly iambic “granny flats.”

The genesis of the idea was fairly simple. We had been discussing whether it would be worth it to rebuild aging garages. The major challenge of the program was not accessibility of capital but rather what we called the “appraisal gap.” Appraisers, tepid on housing markets in the hood after in the mid 2000’s sanctioning six figure loans to houses that ended up selling for $345 as tax foreclosures, were not playing ball. (This is why the Detroit Home Mortgage was invented– and continues its valiant crusade at an albeit testudine pace).

Irrespective of Detroiters obsession with cars, imbued by decades of underdeveloped public transit, garages add value from an appraisal standpoint. But why not add a standalone housing unit as part of the garage? It would create value for homeowners as a rental unit or in-law suite. It would create density, foot traffic, occupancy. Neighbors look out for each other, more neighbors are better at looking out for more neighbors. This neighborhood was bounded by a street notorious for gang violence in the 90’s and 2000’s, but retained a lot of awesome housing stock. Our objective was to try and make the math more equitable for new and old Detroiters who frankly deserved better housing– and better capital structures behind it.

“What about the zoning approval?” I was asked. I was a cocky young man. I reasoned that if they could give Dan Gilbert billions of dollars, they could let a broke housing developer get away with adding a couple of brand new apartment units. It was perhaps less cocky than pragmatic.

Unsurprisingly, the bankers did not buy it. It would admittedly have been a bit of a moonshot, given that we were already struggling with Detroit’s preposterous, so-called appraisal gap– between assessed value and development cost. It would have been a stretch from a financial standpoint to take an $80,000 renovation that did not include a garage to, say, $150,000, to include a garage and an ADU. Of course, bureaucratic bloat and delays ended up adding nearly that much cost after the bank decided to fire the original builders and hire a new team, which threw out the rule book, painted everything grey, and replaced the historic 1920’s solid wood veneered doors with new hollow-core doors. Management lesson: Create and manage ironclad construction scopes from the get-go. And don’t let bankers run the show. But I digress.

III. MERGING HOUSING + INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENT

Beyond this fanciful idea of ADU’s, old Detroit neighborhoods suffered from disinvested infrastructure. Alleys were full of garbage and streets flooded, mostly from clogged storm drains. Basements flooded on the regular. The average home was getting visible moisture from any major rainfall event (let’s say an inch or more), and I would say that having the better part of an inch of standing water in any basement was an annual occurrence.

If we had to dig up and redo a driveway, what if we could redo it with pervious paving?

To make a long story short, it didn’t happen. Too expensive, blah blah blah. But the case was instructive in understanding how we can better think about ways to approach issues that are multifaceted– with multifaceted solutions.

The ADU should be a key development goal for neighborhoods with modest but stable values. In Southwest Detroit, demand for housing is through the roof, no pun intended. When I worked at Southwest Solutions, we routinely had an effective occupancy rate of 100%. If you counted units that needed some basic updates or repairs before they could be occupied, that number was still in the upper 90’s. This was mostly in the “naturally occurring affordable housing” space, or NOAH. The “naturally occurring” is subject to some debate, but it refers to housing that has been made affordable by virtue of depreciation over time rather than by LIHTC or some other financing mechanism. It is relatively unleveraged and is usually older, given that new housing is built with sky-high labor costs, because capitalism. A newer term considered more accurate is CUBA, or “Currently Unsubsidized, But Affordable.”

I’ve often lamented that Detroit’s market is bifurcated into, on the one hand, NOAH in the $300-500 range that is typically barely livable if not flat-out illegal, and, on the other, an ugly loft apartment for $1500 a month with granite countertops and a $187 dishwasher. The Frigidaire Slumlord Special– although a quick peek at Home Despot’s website will indicate that tariffs have driven up prices egregiously in the past couple of years.

But with the advent of the Tiny House era, promoting a challenge to consumer culture and its drive toward ever more McMansionous living, we are afforded some novel ideas about how to think about smaller, more manageable models of space. To be clear, I think Tiny House is kind of a stupid thing. I don’t think it’s going to stick around. But it raises some very interesting ideas about the question of how to finance and build more affordably.

When some random woman you went to high school with, who studied accounting, is instagramming her Tiny House that she is building with her charming but dull looking boyfriend in their backyard, without formal construction skills beyond YouTube credit hours, that’s intriguing– from an academic standpoint, if nothing else. When they’re doing it without the multiple layers of financing and soft costs that invariably accompany a “real” home construction project, that’s downright… inspirational. This must lead us to better conversations about what is between the 2,700 square foot McMansion built by D.R. Horton and the 115 square foot Tiny House that would almost certainly result in mutual mariticide.

IV. EQUITY, COST, AND MAINTENANCE

One of my favorite non-things of the Duggan Administration is the reviled, so-called “rain tax” scandal. The drainage charge, as it is formally known, charges a monthly parcel-assessed stormwater fee based on area of impervious surfaces. During my brief tenure at BSEED, I met an eccentric junkyard slumlord who lived in the suburbs and owned several acres of property in the city. He bragged about being a lead plaintiff in a lawsuit against the city for the so-called “rain tax.” Their bill went from $100 a month to several thousand dollars a month. Let’s look at that for a minute. $100 a month in sewerage charges for about nine acres of all impervious property.

At any level, it’s obviously messed up to imagine this stark, night-and-day shift.

But there is so much land in Southwest Detroit. I intend to eventually demonstrate that the drainage assessments are wildly inaccurate and not equitably distributed. (After a FOIA request, the Water Department’s head counsel told me that I’m not the first person to try and investigate this issue, nor will I be the first person to fail to demonstrate any malfeasance. I countered that if that were true, they’d make their records publicly accessible. She wanted to charge me hundreds of dollars to access records.)

Opponents of pervious installations say that they’re too expensive and require maintenance. But what else requires maintenance? Basements flooding. Yards flooding. Streets flooding and becoming impassable. Repeated freeze-thaw catastrophically damages hardscaping.

Wouldn’t it be preferable to have maintenance-required surfaces that hold up for a longer period of time? Instead of roads that require repaving every couple of years?

Equity, ever a big part of the conversation du jour, has come to represent an apparently nebulous descriptor of residents’ possible access or benefits from a project like GSI implementation. Residents don’t own the GSI, but would directly benefit from its installation. GSI would lower the externalized cost of flooding from combined sewer overflow or otherwise heavy rainfall. Maintenance seems like a relatively small price to pay for a cleaner, greener, less flood-prone neighborhood.

ADU’s take this “equity” question into firmly financial territory, because people then own a physical building that generates revenue. In cases of Southwest Detroit, where the average garage is a ramshackle, centenarian shed, lenders or equity providers could easily help provide access to affordable capital to build new ones.

If we go by my Detroit Park City estimates, we can essentially think of a $165 per square foot cost as creating a new, small apartment unit above a 1-3 car garage for $60,000-80,000. It might be possible to include a couple of apartment units. If we assume a tax freeze, rents at $500 per month ($1 per square foot on the low end) would work out to a net operating income of about 20% for the homeowner. New housing units, better quality alleys, and we all go home happy.

IMPLEMENTATION GOALS

One of my goals in 2020 is to formalize this “GSI+ADU” framework into a toolkit that can be used in Southwest Detroit. The relative density, diversity of uses, diversity of citizens, and broad base of community organizations working in the neighborhood make this the time and the place to do it.