What To Do When The Client Says They Need More Parking

Our redevelopment program in Southwest Detroit is chugging along at full speed, with dozens of housing units under development. Once you get beyond the initial challenge of financing in a market where math simply doesn’t work like it does in other places, one of the more significant challenges in renovating mixed-use buildings in a city with dysfunctional, old planning regulations is that you probably have to petition for zoning approval for a building to be used as a commercial space, because of how many mixed-use buildings predate the development of zoning codes in neighborhoods that are now residential. While modern zoning codes are slowly dismantling parking minimums, most codes as written today usually require off-street parking in most jurisdictions, which is, to say the least, absolutely insane. But when the client says they need more parking, here are some strategies for how to respond.

First, we’ll talk about some background on why this is important in the first place– and then we’ll get into specific solutions.

This I Believe: Abolish Parking Minimums

First, we need to know what we’re talking about. Parking minimums are municipal regulations– usually built into the zoning code- that require building owners to provide a specific number of off-street parking spaces per dwelling unit in a residential building. In commercial buildings, we usually calculate parking minimums based on square footage. How the building owner reaches this minimum is usually not spelled out, as there are many ways to get parking, whether that means including the parking spaces on-site, demolishing an adjacent building, or utilizing a nearby lot.

But there is no real reason why parking minimums exist. They are onerous impositions on developers, driving up the cost of construction, which drives up the cost of housing. It’s not simply a matter of paving asphalt onto free ground, as the ground itself is usually expensive to acquire– and may well require demolition of nearby structures, as mentioned above. A recent Rutgers white paper suggested that the cost of the average multifamily development project is driven up by $2 million because of parking minimums. Two million dollars. Per multifamily project. Multiply that by thousands of apartment buildings that are being built in this country right now, and you’ve got, well, a truly insane number.

Read more about parking minimums here.

$2 million in Detroit terms translates to as many as a couple dozen extra units of much-needed housing.

Per project.

Just because cars.

It gets crazier when you see how many buildings are inevitably demolished to build surface parking. We see this in downtown Detroit. This was one of the purposes behind Detroit Park City, a series I did a number of years ago. Detroit Park City sought to illustrate the development potential of these surface lots. I also learned a ton during that study: that parking is an extremely inefficient land use, not solely from a value creation standpoint but because of how little of an average parking lot is actually dedicated to parking.

Above: SDBA’s Greg Mangan stands at the edge of a lot behind one of the buildings in our program. This project is probably going to involve a modest, paved parking area off the alley, which means that we won’t be adding a ton of hardscaping to a site that is already able to comfortably fit 4-12 new residents in four apartment units upstairs, plus downstairs commercial space. This project may also be cable to combine with a nearby site that has extensive stormwater management parameters, which is fantastic. (DWSD has, in spite of all of its shortcomings, miraculously figured out a way to allow property owners to sort of “share” local stormwater capacity, on a case-by-case basis!). It may also include its own stormwater management system, budget and space permitting.

First: Provide Legible, Comprehensive Data!

The site pictured above is about 50′ wide. This translates to all of five parking spaces (a parking space is typically 8.5′ or 9×18′). However, that’s approximately what the city parking minimums would require anyway within this special overlay district. In the Detroit Park City cases, I suggested that projects prioritize the configuration of pull-in parking spaces that are accessible directly off an alley, because they optimize space and don’t involve a ton of waste. This was also the architect’s conclusion, and it sounds like this will be our best bet to minimize encroachment on what could otherwise be a nice backyard.

Now, for a less exciting conversation I have to have. The space pictured above, another site in the program, fronts on one of Detroit’s few well-maintained alleys (shockingly to outsiders or residents of civilized jurisdictions, the city does not maintain alleys to save money and they are usually in quite disastrous conditions, or are used for dumping grounds). The owner is interested in demolishing the rear portion of this building to add– wait for it- all of *four* parking spaces. It is possible that she could squeeze out a fifth. Including the cost of demolition and any environmental abatement, we are talking about a minimum cost of a few thousand dollars per parking space.

All to house vehicles that will be mostly idle, most of the day. Spaces that will be empty most of the time. That essentially works out to a subsidy of a few dollars per day per car, forever. This is less than one could make by charging money to lease these spaces, or metering them (if the city were interested in doing this, for example).

Is the new parking technically required by code? Well, referring back to that overlay district, not really. This site includes eight parking spaces (pictured) and around eight more street parking spaces. The owner is interested in using part of one of the buildings here as event space, which means that more parking demand would come.

Now, would you rather spend, say, $20,000 to add four parking spaces that generate zero revenue?

Or, would you rather have 800 more square feet in your building that could generate that same amount per year in rent? If the building is 800 square feet and the rents are $2 per foot, that’s $19,200 per year. Seems to me that it might be beneficial to have an additional $19,200 per year than spending that same amount and never making that money.

A neighborhood becomes a destination because of places, not because of parking.

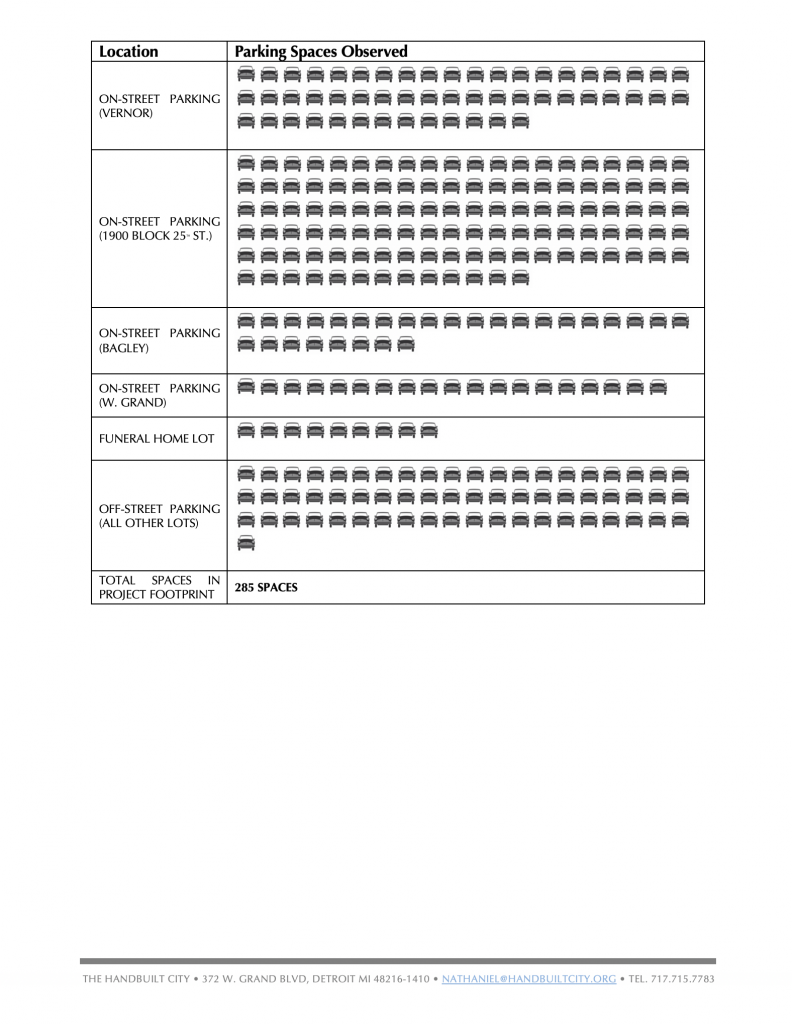

Now, if there does end up being a struggle with parking, there are some other options for us. There is not in this particular section of Vernor, as you can almost always find parking within 50 feet of a destination, although our architect explicitly referred to the neighborhood as “parking constrained,” whatever that means. There are 15 spaces, for example, in one nearby off-street lot, while the owner already has access to 14 off-street spaces across the street. The side street, from which this building is accessible, includes 10+ street spaces, while the entirety of the block to the north (excluding these ten spaces) includes about 2000′ of street parking, something to the tune of 100-130 spaces. There are 46 houses on this block and six off-street parking areas (paved areas far larger than a driveway).

Thus, it seems like we have plenty of space for the cars. No doubt someone looking at my informal study of parking will point out that the largest single chunk of this is all along a single residential street, which includes several hundred feet of curb that goes the whole way up to Toledo Street. Would this not be a long walk for someone visiting one of these buildings? Perhaps, but I also wanted to consider a sensible walk-shed, for lack of a better term. You’re more likely to walk a couple hundred feet if you can park on the same street without having to cross anywhere, than you are to walk a shorter distance that requires you to cross multiple streets with signals (in this case, Grand Boulevard and/or Vernor, both of which have notoriously dangerous car traffic that refuses to yield to pedestrians).

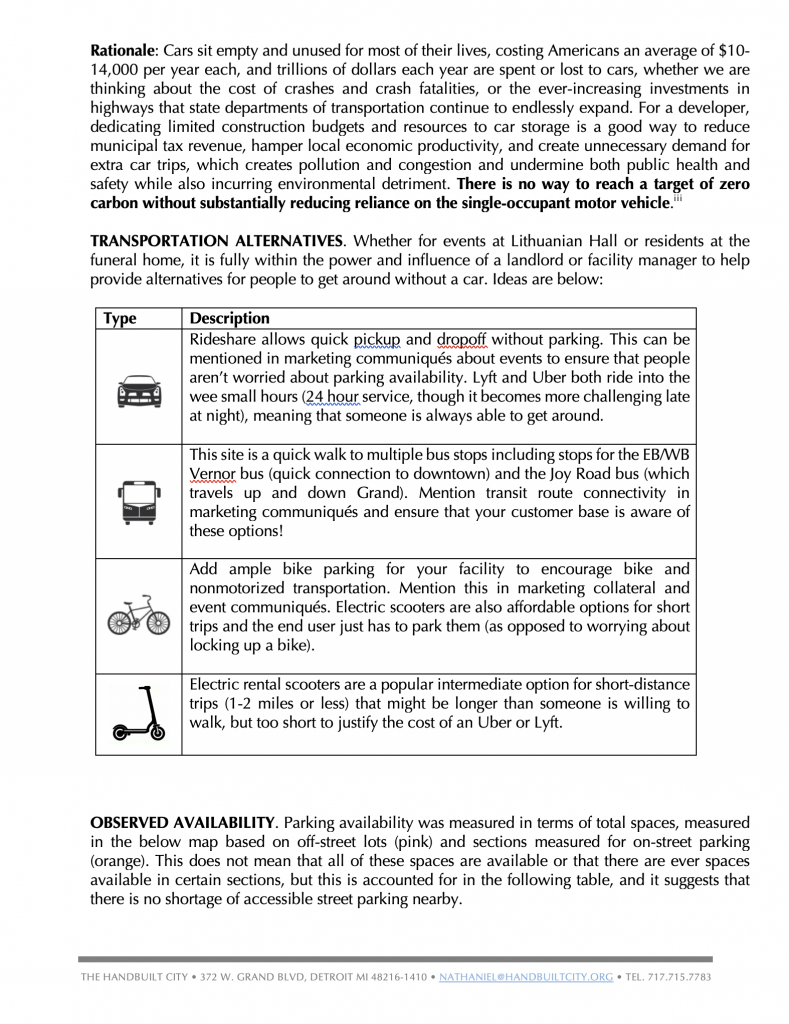

Finally, property and business owners have the ability to encourage their patrons to consider alternatives. We walk to Sicily’s Pizza all the time, for example– although I’m sure even many able-bodied but lazy folks would drive those three blocks. I specifically mentioned transit (easy connectivity with the Vernor and Joy Road buses), somewhat less convenient connections to the Michigan Avenue and Fort Street buses), bikes, scooters, and rideshare. In order to ensure that our whole city isn’t just taken up by surface parking, which eats up valuable land and decreases its productivity and therefore the concentration of taxable revenue, we must focus on providing alternatives and removing guesswork to folks who might be on the fence about them.

It may also be time to consider the Donald Shoupian Parking Benefit District, which involves charging a dynamic rate for parking spaces based on demand to ensure that there is always availability. The introduction of residential parking permits, to ensure that residents consistently have access to parking, is another layer of complexity. But it’s one that we can solve. I certainly don’t think that this neighborhood needs a single additional parking space. We just need to better manage what we have. More parking lots, I’ll say, don’t fit with the character of the neighborhood!

Stay tuned for more exciting content on the SDBA program.