Why Parking Minimums Are Bad.

Donald Shoup, the grandfather of parking theory, has spent a lot of time researching this subject. So, suffice it to say, none of my own ideas end up being particularly original, so I’d prefer to just quote his. Shoup writes in Parking and the City (2018) that the requirement to build parking as part of any project– whether an intentional act by planners, or simply an act that is enforced by planners perpetuating this policy- is bad, if for no other reason than because it doesn’t take into account any of a number of pieces of vital information.

(I’ve been talking about this for years, but this article is a sidebar to an upcoming one about how to navigate your response to the question, “what about the parking”?).

That information includes (bold is directly from Shoup’s text):

How much the required spaces cost to build. The developer has to figure this out. Municipal governments that require parking spaces be added to a project aren’t thinking about the cost implications, nor the fact that it might well drive up costs so far to make a project untenable.

How much drivers are willing to pay for parking. Again, this almost never factors into development financing pro forma, nor does it factor into considerations of the urban context of a real estate project in a neighborhood. Donald Shoup’s main contention is that parking should be priced at a dynamic, market rate that consistently allows access to parking spaces. In other words, if the street parking spaces are all full, it’s too cheap. If the price is $1 an hour and there is still not enough space, it can be raised to $2 an hour. And so on and so forth. This is fair enough until you run into an issue in which a building lacks parking but residents don’t want to have to pay (or remember to pay) every time they come home after work. This can be remedied largely through the development of permit parking districts, in which people can get access to a parking pass if they live in a certain area. This program can also be funded through the dynamically-priced parking– in what Shoup calls a Parking Benefit District, which can provide for all manner of other local civic improvements, to valuably demonstrate how this works in realtime.

How parking requirements increase the price of everything except parking. We can unpack this one by pointing out that adding $5,000, $10,000, or $50,000 to the cost of a dwelling unit can work out to a truly insane percentage of the total cost of construction. If we imagine a micro studio apartment at, say, 384 s.f. built at $250 per square foot, adding an underground parking space at $50,000 will account for more than half of the construction cost per unit. For a 1,200 s.f. unit at the same construction costs, $50,000 is a sixth of the price point. Now, imagine that the construction costs are only $175 per square foot. A single parking space in an underground structure will cost 24% of the cost of that unit. Is there any other product where someone could just jack up the price by 16.7%, 23.8%, or 52%, and you would just buy it without thinking twice? I’m guessing not.

How parking requirements affect architecture and urban design. A city full of parking lots is not a city that people want to visit. Eiffel Tower? No one goes there because of the availability of free parking. They go there because it’s a beautiful structure situated in a beautiful public space. New York? Same thing. There are 70 million people who visit New York City each year. How many of them go there because of the free or available parking? I guarantee you not one. More surface parking also means a hotter city in the summer, and it requires a lot more maintenance in the winter, too.

How parking requirements affect travel choices and traffic congestion. When you know that there is free parking at your destination, you’re unlikely to consider transportation alternatives. This is not as big a deal for someone who is already driving from far away. But most trips are short trips. If you are able-bodied and can walk four blocks, you might just consider it to save $2. $4. $10. Whatever that number is.

How parking requirements affect air and water pollution. As asphalt is more or less oil mixed in with crushed rocks, we should always be thinking about how to minimize its use in urban environments. Asphalt offgasses after it’s installed. It also creates runoff pollution, which ends up in waterways. Old asphalt seems to not be as bad as fresh asphalt in this regard. But there are still microplastics, brake dust, and all manner of other unsavory dribblings from motorcars that permeate into the surfaces.

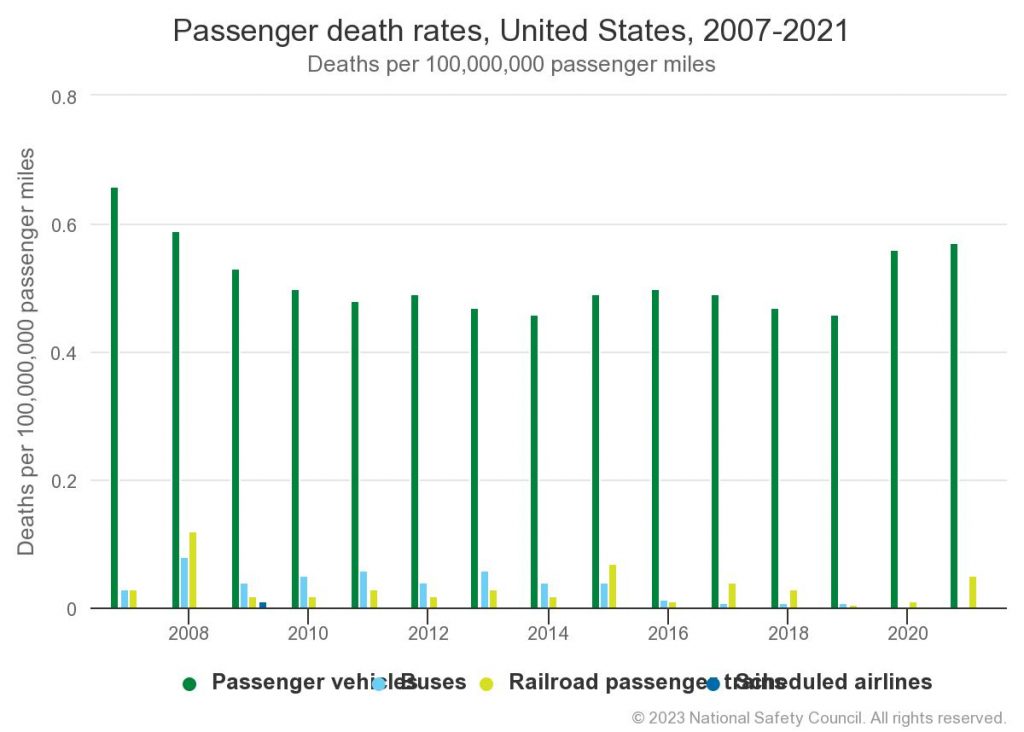

How parking requirements affect fuel consumption and CO2 emissions. Creating more parking creates more of an incentive to drive. Where parking is scarce, it incentivizes carpooling, nonmotorized transportation, and usage of public transit. Public transit delivers more people with less emissions and less fuel, and it’s also generally far safer than driving (see chart). On top of this, and especially referring back to the previous point about air and water pollution, buildings that are occupied are consuming marginally more per square foot than parking, but parkingscapes bear a massive carbon footprint. Concrete uses more than twice as much CO2 to produce than does asphalt.

Conclusions

There is no other comparable example of city government imposing this degree of costly requirement on a developer with no alternatives. Consider, say, sprinklers. Sprinklers are often required for certain types of buildings. But in some cases, they may be forgone in favor of other types of fire separations. I ran into this when living in a loft apartment, which did not have an operable window egress (as would be required for a regular residential bedroom), but which had sprinklers. It is not the job of city governments to subsidize your car. Nor should it be the job of city governments to force developers to subsidize your car. It is time to consider alternatives.