Energy Burden: The Elephant in the Electrification Room

This morning, I decided to go full old school Handbuilt and attend one of the MPSC workgroups on low-income energy topics. You may recall that I used to cover these, and then I stopped going after I got in trouble for attending one at my old job, so I stopped for a couple of years. Anyway, now that I’m ambivalently back in the Mitten, I figured I’d drop in and see what’s going on. Today, we had a presentation from Destenie Nock, PhD, and Shuchen Cong, a doctoral researcher, both from Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh (Pennsylvania represent!). Nock and Cong presented on their work conducting sophisticated analysis of large data sets in utility billing data around the question of energy burden.

This is a topic that is growing in visibility as we start to have complicated conversations at a national scale around abstract concepts like load shifting, and as we start to have dinner table discussions about very concrete concepts, like wondering whether it’ll be cheaper to afford energy if we install a heat pump instead of a gas-fired boiler. It’s a rare intersection of issues that involve opportunities for value creation at the corporate level, improving economic conditions for our most vulnerable populations, and reducing carbon footprint across the board.

What ARE Energy Burden or Energy Poverty?

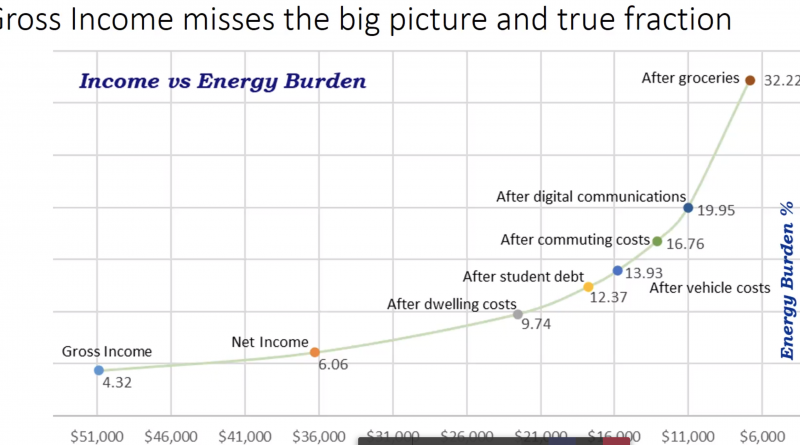

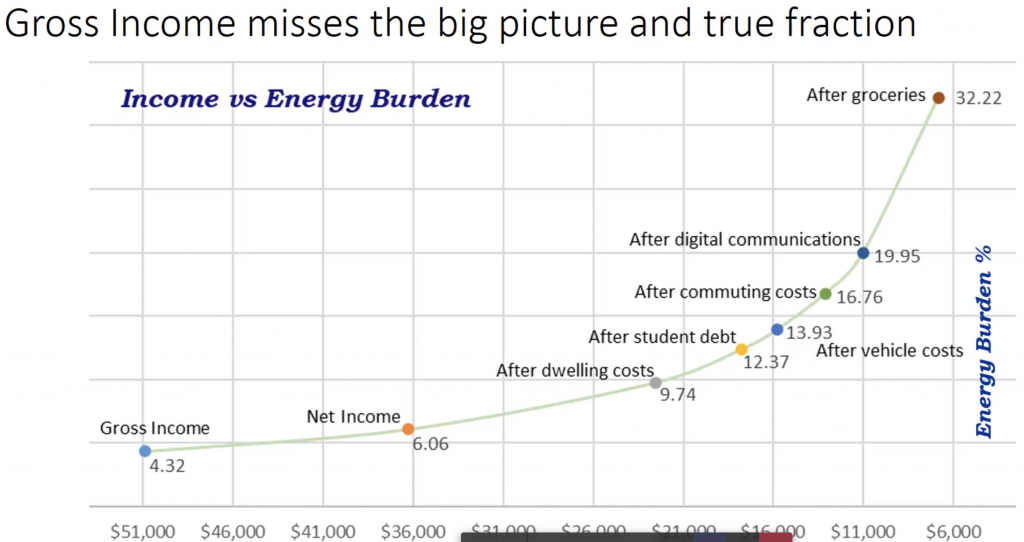

It’s been awhile since I’ve written about these topics, but I used to come to these workgroups all the time! The concept of “energy burden” is similar to the concept of housing insecurity. The idea is that people with less disposable income are more likely to be in a more precarious situation with their ability or inability to pay a utility bill. It gets more complicated, too, because there is an inverse correlation between average housing quality and income level, meaning that the less money you make, the more you’re likely to pay for substandard housing, which may be far less energy-efficient on a per-square-foot basis. Slumlords renting out properties in low-income neighborhoods are less likely to do things like, you know, maintain buildings to code, and they’re certainly less likely to add R-60 in attic insulation.

Many years ago, before it was considered socially acceptable to ask questions about energy burden, the topic du jour was LIHEAP, a program that helps low-income utility customers to pay their bills. I pointed out at the time that, absent a huge increase in funding dedicated specifically to weatherization (building envelope improvements) or energy efficiency, LIHEAP would never be sustainable and would amount to basically just another fossil fuel subsidy. This is an area in which times have changed, thankfully, and I’m glad for the work being done by folks like Destenie, Shuchen, or Tony Reames, formerly with the University of Michigan and presently with the Department of Energy, working on this same stuff. Every presentation I attend on this subject gets into more interesting detail.

Why Energy Poverty and Energy Burden Are So Complicated

At this point, it’s not actually a question of not having enough data, but rather not knowing what to do with the data, whether at a level of analysis (or at a level of public policy, heaven forbid). A lot of time is spent not looking at the raw numbers, but trying to control for number of complex factors. Is the ratepayer a renter or a homeowner? How old is the building? Is it a multifamily building, or a single-family one? Does the neighborhood have shade, or not? This is before we even get into more intense architectural questions: if it’s a new home, was it built to code? If it’s an older home, has it been renovated? What kind of roof? Is urban heat island a problem in this area? Are there complicating factors that could lead someone’s energy consumption to increase after investment in energy efficiency?

The list goes on, but generally, the things researchers are generally looking at are the total numbers of heating degree days (HDD), cooling degree days (CDD), and then figuring out how these index against utility bills, specifically the rates of customers in arrears or facing the threat or reality of utility shutoffs. Utilities are notoriously cagey about releasing these data, because they don’t like it when pesky journalists like me asking questions about how we can improve LMI participation in LMI programs, or, you know, make the world a better place for us all of us. Nock has broken down the data in terms of a variety of economic indicators, behavioral modifiers, and other factors.

Nock and Cong are working on a new platform at CMU called Peoples Energy Analytics, that gets the Handbuilt City seal of approval– in that it’s very much pro-decarbonization, pro-consumer, and pro- reducing operational inefficiencies in ways that can actually improve utilities’ bottom lines. These win-win-wins are extremely rare, and I’ve pointed out on a number of occasions that inefficiencies that utilities persist in thinking about as far as inevitabilities of debt can actually be remedied by facilitating the development of a better and more energy-efficient built environment.

Follow Dr. Destenie Nock, PhD, on Twitter. While Twitter still exists.