BUILD GREEN Act Charges Forward With Electric Transit. Is It The Right Move?

Southeast Michigan U.S. Representatives Andy Levin and Rashida Tlaib, among others, introduced legislation last week to spend $500 billion over the next decade on electrifying public transit infrastructure. Transit electrification has become a big topic as automakers shift their focus away from internal combustion engines at long last. But, as I wrote last year, decarbonizing transportation one SUV at a time, uh, well, won’t work. Mass transit brings with it economies of scale for moving people. It also brings economies of scale for electrification that help all of us. Here’s how it can go down.

Searching For That Spark

Ironically, transit electrification actually began in earnest, for the most part, under the last administration, in a small degree. (I suppose this shouldn’t be too surprising. The Trump Administration’s impressive incompetence means they weren’t actually able to implement much in the way of their, ahem, largely nonexistent agenda. So, this meant that there remained smart people in the government focused on things that smart people are focused on. Like addressing climate change! Even if the, you know, Scott Pruitt and the Andrew Wheeler types did their damndest).

The Biden Administration has moved quickly on its *squints at notes* radical left-wing agenda of modernizing American infrastructure. So, as companies like New Flyer deploy new electric buses, there’s a substantial question about how the infrastructure is going to work to support these buses. Battery prices are going down and technology is improving. So, there’s an ever-growing interest in cities buying electric buses! But, as Han Solo once asked rhetorically to young Skywalker: But who’s gonna fly it, kid? Suffice it to say, it’s not quite as simple as the little DC inverter where you can run an extension cord from your Ford F150 to whatever.

Capacity Challenges

There are a bunch of challenges to implementation of electrified transit. Most of this centers around the issue of utility infrastructure. At the simplest level, this means that there are not enough power lines buried in the ground to support a large number of electric buses. A 120-volt, 20-amp outlet in a house can charge an electric car. But it still takes, well, days. A faster charger requires in the vicinity of 30-60 amps. And a DC fast charger or Level III charger requires even more power still. Most home electrical panels can’t even handle a DC fast charger, but a Level II charger is going to be sufficient for most families buying electric cars, because they can charge the vehicles overnight. (Side note– this will probably make it much cheaper to charge cars in the near term, since power is very cheap at night).

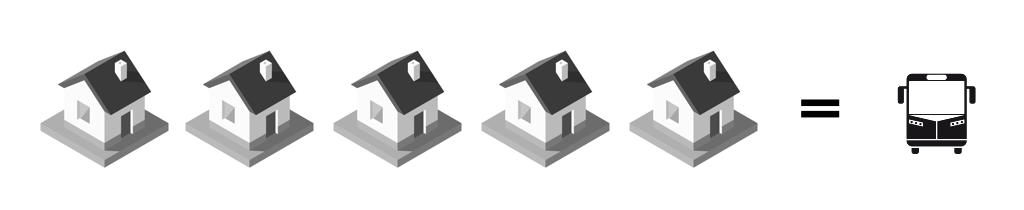

An electric bus, on the other hand, requires a lot more power. In China, DC fast charging for buses uses the equivalent peak electric load of five American houses. A couple of the interviews I did for my thesis research considered this question. If you’re a transit agency, you’re trying to plan for the future. If you’re a utility, you’re doing the bare minimum required by law. DTE did not respond to multiple requests for comment on this. They did, however, send over a few regulatory filings, that showed that, by the company’s own admission, it’s going to be very hard for the utility to support fleet electrification, let alone market penetration of electric cars above around 10%.

As local demand increases, the power grid struggles to maintain power quality. Line voltage drops the farther away you get from the substation. This becomes a bigger issue when you have massive amounts of power being drawn away for, say, a transit depot powering a bazillion buses, or what have you.

The business benefit of transit electrification is that it gives utilities a predictable revenue stream– and therefore a good incentive to modernize the grid.

Whose Line Is It Anyway?

In one example in my research, the city of Detroit wanted to install chargers for a couple of new electric buses. DTE, our local utility, agreed. But the city wanted to install additional capacity to effectively futureproof its bus charging infrastructure. In other words, they might have three electric buses now, but they want to be able to charge ten in a few years without having to, say, dig up an entire city street again to lay new power lines. DTE balked, saying this would cost millions– and they wouldn’t do it.

Utilities argue that they are only investing in things that have an immediate ROI because that’s how they have to operate. But mysteriously, they’ll then turn around and spend millions of dollars lobbying to keep residents from installing rooftop solar. Funny how that works. The business benefit of transit electrification, though, is that it gives utilities a predictable revenue stream– and therefore a good incentive to modernize the grid. Realistically, companies producing the electric vehicles need to coordinate with utilities, municipalities, and third party charger companies. In many cases, they are doing this– but absent national or even regional frameworks to encourage this practice, it’s going to be a haphazard, fragmented, bottom-up approach.

Why Transit Electrification Matters More Than Car Electrification

Some basic facts that we know already. We know that buses are more efficient at moving large numbers of people than single-occupant vehicles (a.k.a. cars). We also know that bus exhaust from diesel engines is pretty nasty. There’s a growing body of evidence to support that air quality near things like bus stations or, uh, customs plazas, is very poor and very closely associated with higher rates of respiratory illnesses and cancers.

The exact science of why diesel in the first place is actually kind of interesting. Diesel engines use a different cycle of ignition than do standard four-stroke gasoline engines. They operate at higher efficiencies at low speeds. But the problem here is that diesel exhaust is, well, gross. Many jurisdictions have switched to natural gas for buses, especially in areas where air quality is already poor. But this has become a talking point among “let’s-not-challenge-the-status-quo centrist” types who call gas a “transition fuel.”

Diesel isn’t going away, as it continues to have applications in, well, giant engines, especially giant engines used in places where electrification would be difficult (railroads through the desert) or impossible (the middle of the Pacific Ocean). It’s possible that we’ll see increased interest in biodiesel. But biodiesel has struggled against the heavy government subsidies for the supposedly environmentally-friendlier gasoline alternative of ethanol. And diesel engines for passenger cars struggled to catch on in the American market (versus Europe).

Modernizing Transit = Modernizing The Grid

Nay, I suspect it’s probably just time to go full, uh, steam ahead on transit electrification. This means development of higher-capacity grid infrastructure that expands opportunities for distributed and decentralized power generation. If you have a bunch of electric buses, you now have more of an incentive to install rooftop solar in the giant bus terminal building. You could install solar canopies over outdoor paved area, too. And so on. Convincing the utilities to move faster than they are will be challenging, but it’s a win for all of us. Sorry, fossil fuel paradigm– you had a good few centuries. Let’s get it done.