What If Every Street Project Required Rightsizing And Traffic Calming?

Recently, I’ve been running a couple of morning errands in a car– don’t drop your monocles all at once, people, I do sometimes drive places– and one thing I haven’t missed about driving is the absolute insanity of summer construction. In a more prosperous part of the country, street renovations involve well-marked detours, highly legible arrangements of traffic cones, pylons, and J-barriers. Heck, even sidewalk renovations back east often involve installations of things like ramps for wheelchair users. Why these things aren’t popular in Detroit is fairly obvious (n.b. a “deal with it, peasants” attitude around infrastructure development). But what’s not as obvious to me is why we can’t figure out how to mandate better street design when we do have these inevitable and frequent street renovation projects.

It could involve rightsizing the street, or it could involve installing traffic calming measures. Let’s take a look!

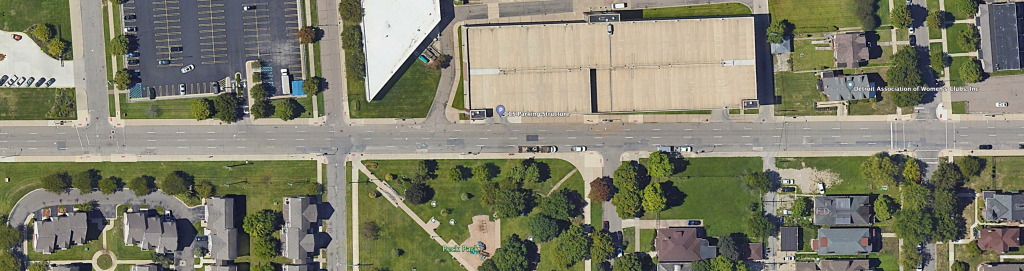

The above image is a Google Earth view of a particular stretch of northbound street in Midtown Detroit. It is a particular sub-district of Midtown that has a mixture of wonderful historic homes and blocks where more wonderful, historic homes used to be, before they were demolished and later rebuilt in the image of suburban, vinyl-sided beauty, like the mayor’s native Livonia. It’s got some nice blocks and some not-as-nice blocks. It’s surprisingly mixed-income for a neighborhood that is increasingly (shockingly) exorbitant. And, of course, it’s Detroit, so it’s also defined by a huge sea of parking lots and other paved street area.

We’ve also got these peculiar streets that are designed to handle high throughputs of traffic, but also allow parking, usually on either side. For a higher-throughput thoroughfare, it makes sense to have two travel lanes rather than just one. But this is not a high-throughput street. It’s a minor side street. Why does it need to be four lanes?

Shockingly, it doesn’t need to be four lanes, but this is a problem of the “business-as-usual,” box-checking approach to infrastructure management. I’m surprised that the Chief Wolverine Lord High Technocrat of City Infrastructure isn’t on the case, but I’m also surprised that none of these street projects contain design standards for rainwater management, landscaping, or traffic calming.

Proper Lane Width

The first thing I’m thinking about is whether the street itself is too wide in terms of the lane layout. Road engineers prefer wider lanes because it makes drivers feel comfortable going much faster. For safety, this is obviously a disaster. Road engineers like faster, because it contributes to modeling that shows that these roads can handle higher throughput of traffic at higher speeds. Who believes this is a good thing? Road engineers. Does it actually increase throughput of traffic? Not really! The reasoning is that streets aren’t actually highways, so there’s a lot of stop-and-go. Depending on how you figure it, cars don’t move through cities much faster than at a speed of about 10mph on local streets. That means that forcing the traffic to slow down from a peak of 47mph to a max speed of 25mph is unlikely to actually reduce the total travel time between points, because of things like stop lights, stop signs, and, of course, traffic congestion.

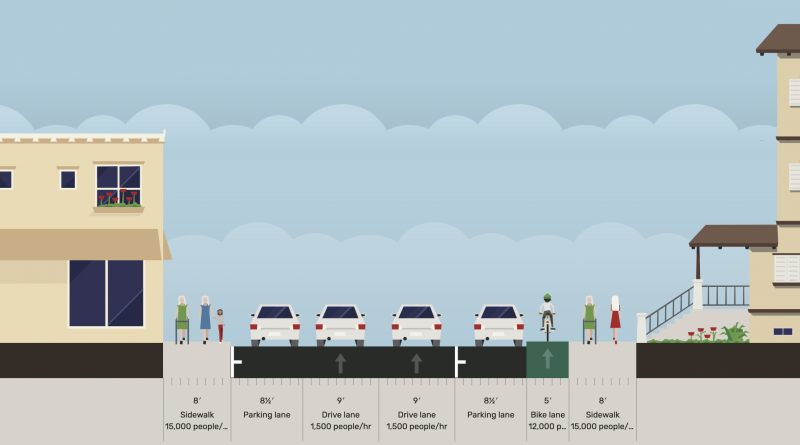

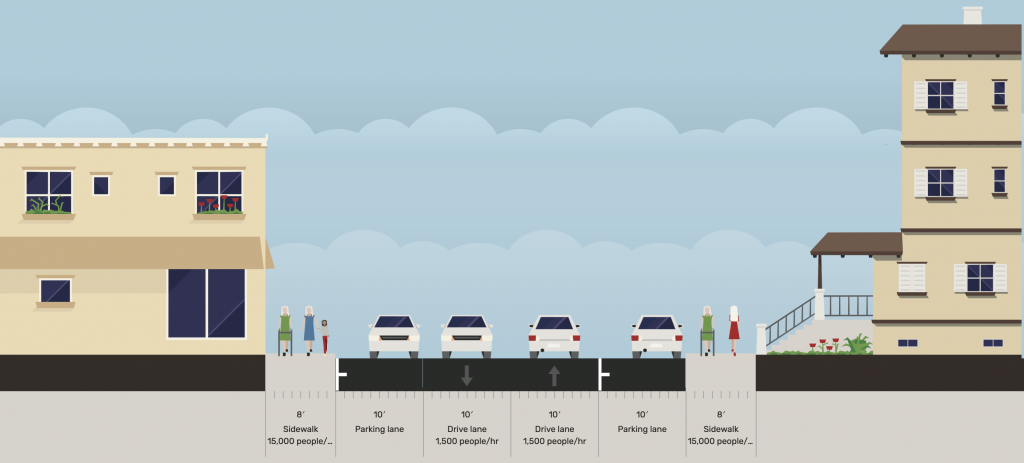

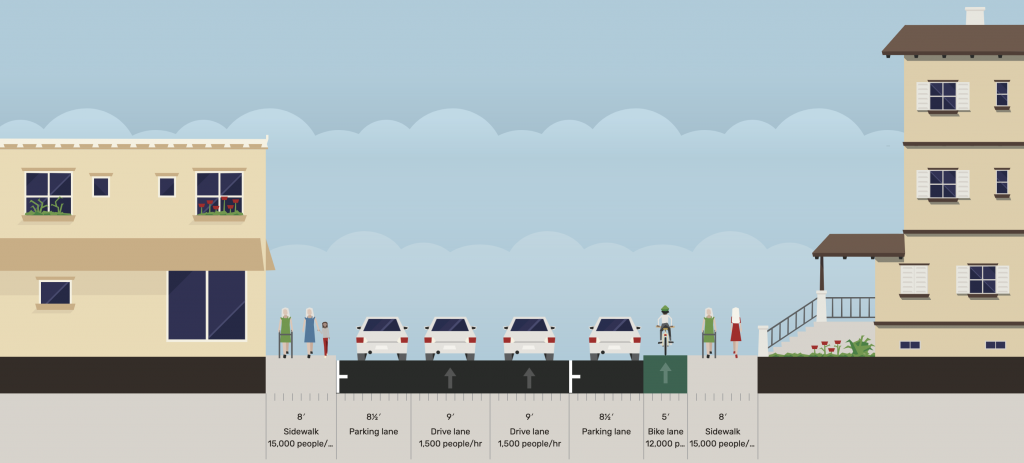

In the illustration above, we have the new street layout. This section of street is about 40′, which is enough to support four travel lanes at 10′ wide each. NACTO cautiously suggests that it’s possible to get even narrower than 10′ for a travel lane. For comparison, a parking space is nine feet wide. If we maintained the Michigan divine mandate of plentiful free parking, we could maintain both parking areas on either side of the street, but make each a foot narrower (to normal parking space size), and then narrow the travel lanes by a foot each, which would leave us enough space for a meager 4′ bike lane. This doesn’t lose us any lanes.

How do we get to this point? A safer city with safer streets? Curb extensions, marked crosswalks instead of just the suggestion to please don’t murder pedestrians? I’m not entirely sure. It requires political will to overcome the stubbornness of engineers who are convinced that there is only one way to do things, for one. But it also requires people to ask questions about why we must insist on continuing to do things the same way, over and over again, when that’s clearly not working.