The Collapse Of SVB Is A Big Deal. It’s Not a Catastrophic Big Deal.

The tech world and the finance world are both abuzz this week over the nearly overnight collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (a.k.a. SVB), a bank that had not been on most people’s radars outside of the tech world until, well, the past week. The FDIC, wasting no time, has already auctioned off most of the bank’s assets. It wasn’t really on my radar except that Matterport uses this bank to process payments and sent out a notice about it. Catastrophists argue that banks don’t really fail in the United States, so this is a BFD. And, paraphrasing the words of a drunk woman at the Fowling Warehouse on Friday night, if rich people don’t have access to capital, they won’t create jobs, and that will end terribly for all of us, so why shouldn’t we bail them out?

I’m looking at this from a few angles. I’m also concluding that it’s not the end of the world, and I have a few data points to support this. Even as I type this, I’m getting a news alert that another bank has collapsed. A situation exacerbated by the Fed’s crusade to send interest rates, like Dogecoin, to the moon? Possibly not unrelated. Domino effect, though? Probably not. I’ve been wrong before, but I don’t think I’ll be wrong about this one. But first, let’s understand a bit more about the situation we’re in!

Bank Failures: The Case For Interventionist Government?

If you remember your history books, the aftermath of 1929 gave us the banking regulations that we have now– at least in terms of the authority exercised by the Federal Reserve and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which was established in 1933 as part of the Banking Act (a.k.a. Glass-Steagall). Thousands of banks failed from 1929 through the Depression, with around a third failing in the first few years. The crash of 1929 and subsequent Depression wasn’t caused by any sort of fundamental economic dysfunction (like a grain shortage or a war), but rather by the irrational exuberance, if you will, of speculative investment. Glass-Steagall’s reforms were mostly aimed at reining in this wild speculation by limiting the speculative investment activity that banks were allowed to engage in. But the FDIC was a huge step forward in that the federal government agreed to directly assume liability for deposits up to a certain amount.

Of course, there had to be strings attached– among them increasing things like the reserve ratio, which dated back to 1913, when central banking in the United States was established as we know it. This was a number that– sensibly, given the bank runs of the Depression- required banks to keep a certain percentage of deposits in cash as opposed to reinvesting that money in other loans or investments. The idea of fractional reserve banking has long been a cornerstone of American wealthbuilding, as long as you were One Of The Good Ones to begin with (a.k.a. the landed gentry); Mehrsa Baradaran focuses extensively on this in The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap— and the implications for creating wealth for people who already had plenty of it. (The reserve ratio has since been eliminated completely in 2020 under the Trump Administration and Jay Powell ostensibly in order to free up cash for lending and consumer spending. We’ll return to this later!).

Depository Bank Vs. Mortgage Lender vs. Investment Bank?

So, the federal government got into the business of saving people and saving businesses during these economic crazy times we’ve had in this country. Did they also create them, though? If we use the Charles Perrow lens and consider giant liberal market economies as complex technological machinery, the crashes, the regulatory reforms that they precipitate, and other legislation or policy that might well lead to a future crash, might well just be considered Normal Accidents. An economic bubble is, after all, sort of like a nuclear meltdown, right? A nuclear reactor has a system of inputs and outputs that have to be carefully balanced in order to be sustained in a predictable fashion. Mess with those inputs and, well, the phrase is abbreviated as FAFO, which stands for “mess things up and we are going to have some problemos.”

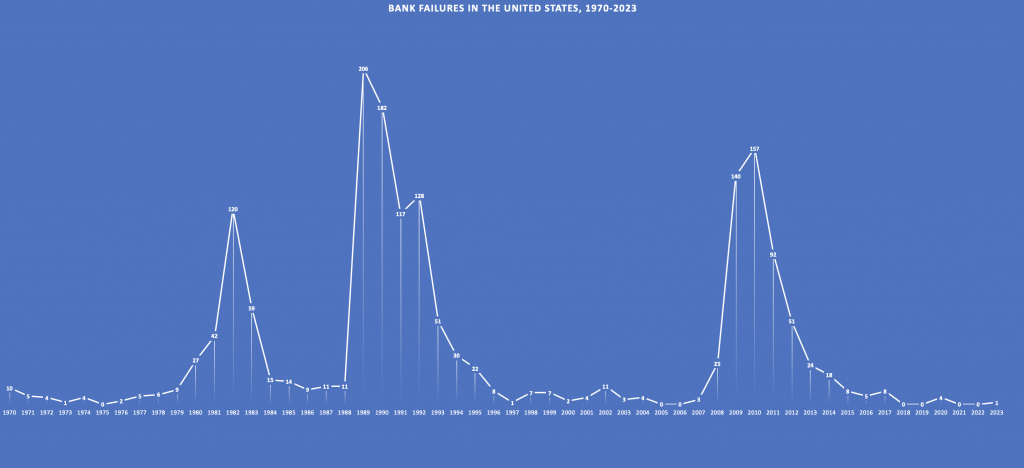

If you look at the past 40-some years, we’ve had two– count ’em- major banking crises, plus a few recessionary implosions of varying sizes and descriptions. Yes, the vaunted world of free market capitalism has had not one, but two monumental failures of the banking sector! Mind you, this is separate from just “recessions” or “bubbles.” The biggest was the Savings and Loan crisis of the 1980s, which dragged into 1992. The early 1980s also saw a string of bank failures, arguably following the deregulation of the banking industry by way of the DIDMCA in 1980, a signature legislation of the Carter Administration (passed by Congress with broad bipartisan support, no less). The S&L crisis saw hundreds of banks fail– about a third of the 3,000-some savings and loan banks in the entire country.

In the 80s and early 90s, most of these banks were savings banks– depository banks, that is- and they weren’t wrapped up in a tech bubble or investment finance. Rather, they made bad decisions, around leverage and risk. And they were empowered to make a lot of bad decisions at scale by poor public policy.

Banking in Bubbles

Comparatively, the dot-com crash erased a couple trillion dollars in value from the economy, and the NASDAQ 78% of its capitalization from its peak. On the scale of bank failures, though? The dot-com bubble barely rated a blip. The subprime crisis of 2007-2013 was a happy medium of catastrophe on both sides, seeing both a substantial market crash as well as a number of bank failures that, while peaking in 2010, took the better part of a decade to subside completely. Of course, these two crises were largely not a matter of consumer banking, but rather a matter of investment finance. The banks that went under in 2007-2013 were largely leveraged to the hilt and overexposed to complex derivative products based on mortgage sales. Most of the people in the companies using these derivative instruments didn’t even understand them, and there was little to no risk control.

Hence, boom. There is one condition, and one condition only, that enables risky money managers to continue managing money in a high-risk environment, and that’s the condition of continued growth. This is true in finance as well as in urban planning, if you’ve followed Texas’ $85.1 billion highway expansion plan, which is all predicated on endless growth that isn’t gonna be a thing forever (you can quote this article in 20 years when the state of Texas is more broke than Michigan and it’s the fault of the highway spending). The second sales growth starts to slip, companies have to figure out how to grow more, cut costs, or both. And the second sales or revenues start to slip? That’s when managers start to hit the panic button. Add additional pressures– like a Federal Reserve taking a super aggressive approach to controlling inflation by rapidly raising interest rates- and it’s a whole thing.

This is exactly what has happened with SVB, Signature, and, apparently, a few more. Tech valuations, which are frankly still way too high, collapsed in 2022 after years of an upward trajectory with only a limited rationalization based on fundamentals. In other words, sales were good, but they weren’t good enough to justify some of these insane valuations. (I raised these points years ago, and all of my finance friends told me I was full of it. I may have been! Today, a few of them are now out of jobs).

Protective Policy Reform?

So, back to this interventionist federal government. Is the government bailing these banks out?

Well, not really. A lot of the money the FDIC and friends are using to shore up cash deposits is coming from a fund that was explicitly set up as a product of the last recession. That fund reportedly has around $100 billion in it. The federal government is confident that, even if it overshoots– perhaps over-guaranteeing liquidity of assets held in SVB, Signature, and others- that it can recoup the money through ongoing fees it’s already charging to existing banks.

Apart from this fund, which may well be completely exhausted as a product of these two bank failures, we’ve had little meaningful reform in the past two decades. The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (a.k.a. Dodd-Frank) in 2010 expanded the FDIC’s deposit guarantee to cover up to $250,000 in cash deposits. The average person has far less than this in savings, so, most accounts with far more money are either venture-funded startups or really, really, really rich people, neither of whom I feel terribly bad for if they lose their asses in stonks and tech bubbles. Dodd-Frank also created some restrictions that have gradually been dismantled in the interest of pursuing a “business-friendly regulatory environment,” in the same vein as that pesky train rule that the Trump administration got rid of just in time for East Palestine.

So, apart from the fact that Republicans have been trying to eviscerate this signature Obama era legislation since, well, forever, Dodd-Frank has probably reduced the likelihood of bank failures. It doesn’t seem to have reduced the risk of bubbles.

But here’s why we shouldn’t be too worried:

1. SVB Is A Product Of The Tech Bubble, Which Has Mostly Already Deflated.

SVB simply stretched itself too far. This didn’t become apparent until it was too late. One colleague, a veteran of the banking sector, pointed out that SVB had been without a risk office for about a year at the time of the collapse. This seems like an egregious governance failure, but it’s not the single cause of why the bank would fail. Losses come in two forms: realized and unrealized. An unrealized loss is when you hold an asset that loses market value, while the “realized” loss is when you sell it and get $5 when you paid $10 for it. You can write off that loss in most cases.

That’s fine until the whole thing goes off the rails, which it started to in December as the bank began to post not seven, eight, or nine-figure losses, but eleven-figure losses (that’s the tens of billions of dollars, if you lost count). This came to a head just in the past week as frantic depositors withdrew tens of billions of dollars. You’re allowed to hold an asset and say it’s worth what you paid for it– which might allow you to leverage that asset to buy more assets, for example- but eventually this asset must be “marked to market,” which means that it has to basically be trued up to whatever the current market value is. The tech downturn occurred last year because– say it with me- trees don’t grow to the moon, but, secondarily, because the Fed began to raise interest rates to try and rein in an overheated economy, overheated consumer spending, historically low unemployment coupled with high wage growth, and a soaring stock market.

2. The Tech Bubble Also Included Cryptocurrency.

This is another thing it’s worth me getting on a soapbox about for a moment.

Cryptocurrency has lost a couple trillion dollars in value from its peak. Now, that’s US dollars, mind you. Cryptocurrencies don’t have any intrinsic value, which is why in my opinion– what has always been my opinion- you should be extremely conservative about investing in them. If the idea was to replace the US currency, then, uh, how are you gonna convert that Bitcoin into whatever you’re actually going to buy? Gonna take it to the grocery store? In other words, people were treating cryptocurrency as a banking institution or even a safe haven asset. It’s much more liquid than other historical safe haven assets, though, like gold or silver. In comparison, it would take some gigantic catastrophe for the prices of precious metals to collapse overnight.

The same cannot be said for some electronic, not-real currency governed by an algorithm, operating in a Wild West kind of market with no risk controls around investment. Remember marking to market? Well, the average large cap stocks– the big companies everyone has heard of- typically only fluctuate a maximum of a few percentage points in a day. Even the so-called stablecoins aren’t looking so stable anymore, to the point that crypto traders are warning of the possibility of a huge price shock rippling out from the collapse of not only SVB but also stablecoin Circle.

3. Bubbles Are Common. Bank Failures Are Extremely Rare.

Even the most cantankerous Marxist– not that I know any- looking at the United States in 2023 will probably concede that this country has a very stable banking system. We don’t have massive rates of inflation like they have in even some modernized economies like Argentina. We don’t have widespread shortages of cash, which they ran into in India in recent years. Sure, we do have bubbles, and that’s because we’re a nation of wildly innovative, utterly reckless entrepreneurs– who like to operate in an environment with as little regulation as possible. Yes, there are ways to fix this, but this article has already put some of you to sleep, so I’ll save that for another 4,000-word piece later.

Anyway. Inflation sucks right now, and yes, we did see some major disruptions during the pandemic, although I’d say that inflation is largely caused by companies jacking up prices in a desperate attempt to prolong the business cycle. That aforementioned cantankerous Marxist, of course, might argue that the US economic system’s vulnerability to these massive bubbles and boom-and-bust cycles demonstrates the fact that it’s not as stable as we think it is. That’s a fair point. If we’re thinking about bank failures over the past 53 years, well, there have been a few. But there haven’t been any (at least that I was able to find in my research) in which depositors actually weren’t able to get their FDIC-insured bucks. (If you had more than $100,000 in cash, well, that’s probably just bad money management):

Again, read my lips, Mr. Nixon and every president since: No Lost Deposits! People lost huge amounts of money in the crypto bubble, the dot-com bubble, the current implosion of the tech bubble, and the mortgage bubble. Maybe the Fed should have looked at increasing rates during these instead of just keeping them at zero? Who knows, I’m not an economist.

Are We Past The Worst Of It?

Maybe! But then again, maybe not! Either way, that doesn’t mean that the average consumer should be terribly worried about their personal finances. I got a notification while writing this article about SVB on Sunday evening that a second bank, New York-based Signature Bank, has also collapsed. Fear of financial contagion roiled markets this morning, especially in the sector of small and regional banks.

My father is always calling me and telling me I need to buy shares in these small, regional banks. “They pay a good dividend!” They may well– they are usually geographically constrained in competitive markets, they have relatively predictable cash flow, and they’re diversified enough that they can usually survive various bubbles or downturns without too much trouble. But they took a beating today. Metro Detroit local favorites Comerica (CMA) and Huntington (HBAN) were hammered with losses of 27% and 17%, respectively– in a market that rarely sees more than a few percentage points in a day. I would be more concerned about what this panic selling means as far as the scarcity mindset of the average investor than I am about the implications of two banks collapsing for the broader economy.

How To Rethink Growth? How to fix it?

But, going back to the drunk woman at the bar: should we be worried about broader economic contagion spreading from these because of how rich people create jobs? Well, I’ll say the same thing I told her: rich people do create jobs, but most economic growth comes from the lower levels of the economic pyramid. This is a simple matter of mathematics. The bigger you get, the harder it is to grow. This is why small companies have much higher failure rates but also much higher growth rates on average. A tiny company could conceivably double its revenue in months or years, versus, say, a trillion-dollar company, which doesn’t really have much room to grow to two trillion except perhaps through market capitalization. (We don’t really have antitrust laws in this country, which is a story for another day!).

SVB was heavily invested in the startup world and the tech world, being located in, well, the “SV” part of its name. Startups can grow at crazy rates. But plentiful research shows us that chasing the next big thing doesn’t actually pan out too well over time. The majority of venture capitalists don’t perform much better than the stock market, if at all. They just happen to have a lot of money. Do they drive innovation? I mean, maybe. I don’t know. But does that mean they have a good business model? Yeah, absolutely not.

Think about the small businesses in your local community. Imagine that for every one of them, there’s probably at least one or two more that you don’t see. But are any of those folks borrowing from a bank like SVB? Probably not– if they’re located in Dearborn, Michigan, Pueblo, Colorado, or Lancaster, Pennsylvania. This is where most of the growth actually happens. Capital is far more fungible, supply and demand curves far more elastic, and, generally, enterprises much more dynamic and flexible, at the smallest, most local level. Capital is limited at this level because over the past half century– the period referenced in the above chart of bank failures- we’ve seen regulation aimed at reducing the risk of catastrophic collapse, but not much in the way of programmatic attempts to improve the accessibility of capital to entrepreneurs and small businesses.

If nothing else, I’m wondering whether this bank collapse will help us think more about what kinds of businesses could actually use more liquidity to grow– normal companies in normal places, not “the next software company in Palo Alto.”