“Bike Lanes Are Against My Morals,” Says Ohio Woman

Especially over the past few years, many headlines in non-satirical news media are often indistinguishable from those in the Onion. Such was the case on a recent NUMTOT post, which highlighted a segment in which a woman says at a community meeting in Bexley, Ohio, a wealthy suburb of Columbus, that bike lanes were against her morals. Reader, I spat out my morning coffee. I kid you not. You can view the clip below, but it may well kill some brain cells. It raises a valuable question, though: While we know a lot more about the best practices for managing parking in the modern day, how do we, as planners or as community advocates, convince these people?

Well, it begins with markets. And it ends with livability!

Have Your Cake And Eat It, Too

I always say that it’s often possible to have your cake and eat it, too, but it’s not possible to have your cake and eat it, three. (Yes, I’m very clever). For example, it’s possible to have free parking and walkable, drivable streets. It’s also possible to have free parking and adequate, accessible amounts of parking. It’s not possible to have all three of these. In areas with lots of free parking, there has to be so much space dedicated to parking that it reduces walkability, drivability, and vibrancy of a streetscape. When I say “drivability,” I’m referring to the ability to easily find a parking space without having to circle endlessly, or without having to go way out of your way to find somewhere to park.

In the town where I attended college, for example, there was free street parking and a free municipal lot that occupied a large chunk of a block. Business owners parked in front of their own businesses, reducing the availability of parking for customers. Unregulated, this was popular because it was free. But it also meant that people would complain about a “lack of parking” if they had to walk more than three or four spaces (not even kidding) to get to their destination.

if parking is a scarce resource, it’s too cheap.

On a recent trip, I was towing a U-Haul trailer, which made street parking kind of a necessity. But even in the downtown areas of four separate downtowns, in Kentucky, Tennessee, and Alabama, we were able to find street parking without circling. It was occasionally even free! Taking the gospel of St. Donald of Shoup, for example, we can say that if parking is a scarce resource, it’s too cheap. This doesn’t mean you can’t provide preferential access to parking for differently-abled people. In fact, it means you should use any revenues from parking explicitly to make the built environment more accessible for differently-abled people, lower-income people, carless people, cyclists, pedestrians, the elderly, and, importantly, children.

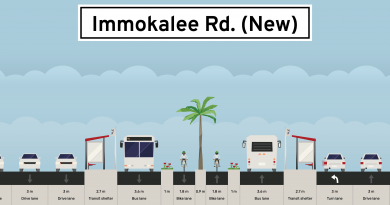

Building and maintaining safe, livable, walkable, accessible, vibrant neighborhoods isn’t rocket science. It’s just a question of checking the right boxes. In the case of parking? Bike lanes, I’m afraid to say, might well eliminate a parking lane. If you want to compensate for that, make sure the parking that remains is efficiently designed— and for crying out loud, make sure it’s priced according to what the market will bear. The government does not owe you free parking. Ensuring that we appropriately account for this otherwise massively publicly subsidized resource means that cities will be accessible, safe, and equitable for all, not just for car owners.

Read The High Cost of Free Parking or Parking and the City by Donald Shoup.