Greenways, The Ultimate High-Density Corridor Development Tool?

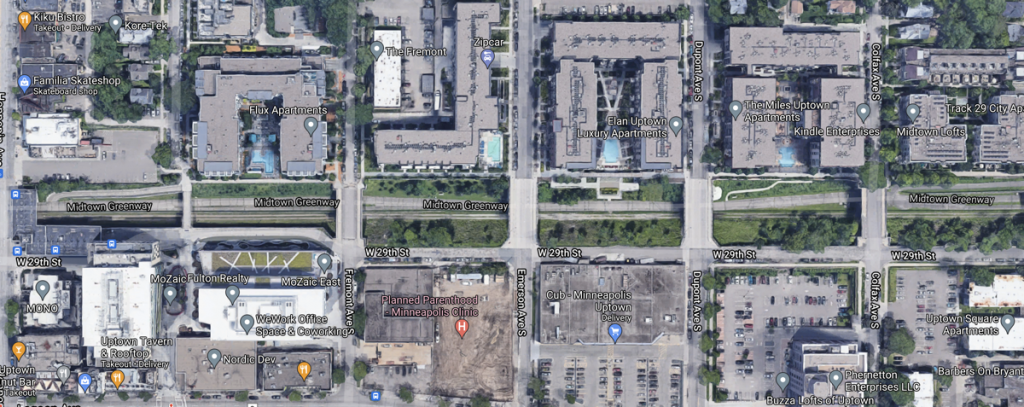

My recent weekend-plus trip to Minneapolis coincided with the opening of the construction of the Joe Louis Greenway in Detroit. I enjoyed an early evening stroll down Minneapolis’ own Midtown Greenway, whose corridor has seen a huge amount of higher-density real estate development in recent years, so I was thinking about a comparison between the two (rather unlike) cities. While the Greenway just celebrated its 20-year anniversary, it has been expanded and renovated over the years, seeing major increases in traffic. This has further punctuated a building boom across the city that is adding a pretty spectacular thousands of units per year. The boom also includes speculative development (development without a specific buyer or tenant identified) and doesn’t seem to be limited to any specific geography as it is in Detroit. What kinds of things should we be thinking about when we’re looking at greenway development?

“En Avant”

It’s an impressive thing to see in a city that saw six-figure population loss from the 1950’s through the 1980’s, and which was pretty stagnant in population terms between 1980 and 2010, when growth really picked up. Minneapolis is still not at its midcentury peak population, but demand doesn’t seem to be slowing down. COVID has been great for sellers across the country as new housing, especially multifamily housing, has been in extremely short supply. In Minneapolis specifically, there’s also a nice thing about being close to this much water– as opposed to in the arid western reaches of the Sunbelt or the hurricane-prone Gulf Coast, for example. In hard numbers beyond just building permits? Looking back at my last piece on red-state-blue-state, Minnesota’s doing quite well. One wonders whether we can at least in part credit the progressive politics? Hell, the French “en avant” (forward!) is in the city’s slogan.

From Minnesota Post: Brent Wittenberg, vice president with Minneapolis-based Marquette Advisors, says that nearly 6,000 market-rate units were completed in 2019 and another 8,000 apartments could be delivered this year. Beyond that, his firm is projecting another 18,000 units in 2021 and 2022.

Meanwhile, Back in the Paris of the Rust Belt

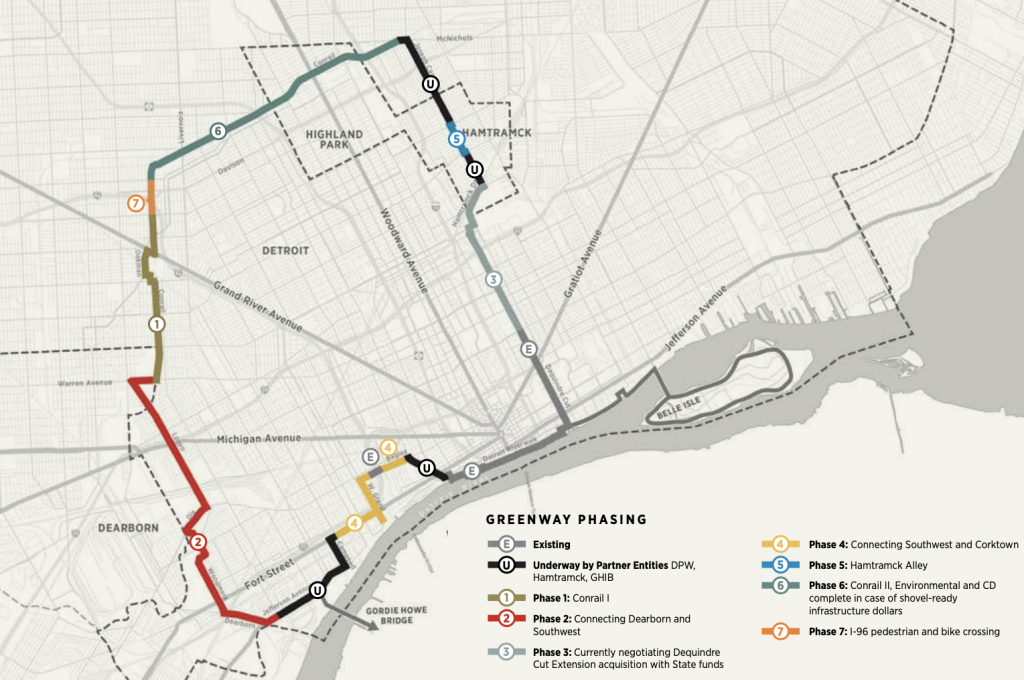

Detroit’s announcement of the Joe Louis Greenway raises questions for me thinking about the two cities in comparison. The Joe Louis Greenway is a $200 million project that will run around the city in a ring, or whatever the mostly-rectilinear approximation of a ring is. Resident concerns around gentrification have been balanced with the promise of hundreds of millions of dollars of new investment. Review the 134-page JLG framework here. It’s an impressive document, even if the degree to which it outlines the real estate development and zoning reform questions only indirectly. (Unsurprisingly, the city of Detroit did not respond to a request for comment, but we will update this if they do!).

Report: Connecting Neighborhoods Creates Jobs, Unlocks Development Potential

The report notes: “As greenways across the country have demonstrated, the Joe Louis Greenway’s ability to connect neighborhoods to recreation and jobs will create real estate value along its path, and unlock development potential. This real estate value will increase home values for the 14,300 homeowners that live within ½ mile of the greenway, increasing home equity and household wealth—with tax increases for homeowners limited by exemptions available within the city as well as State laws.”

Encouraging language alone has not assuaged fears of gentrification in a city that has spent more money on corporate welfare in the past year than it will likely ever spend on the greenway in its entirety. Detroiters are understandably skeptical that the city’s “take what we can get at any cost” mindset will actually result in the rising tide that they claim. There’s also evidence that, well, greenways might indeed cause gentrification.

Comparing Detroit and Minneapolis, it’s hard to gauge this question as well in Minneapolis. The Greenway connects some of the wealthiest neighborhoods along the shores of Bde Maka Ska, Lake of the Isles, and Lake Harriet in the west, and mixed-income neighborhoods, especially east of the interstate. Uptown and South Minneapolis have long had stable, middle-class neighborhoods, in spite of macro level population loss in the city as a whole. The higher-density development immediately along the Midtown Greenway largely replaced low-density light-industrial uses, not, as freeways often did, dense residential neighborhoods.

Questions about the Future of the Joe Louis Greenway for Detroit

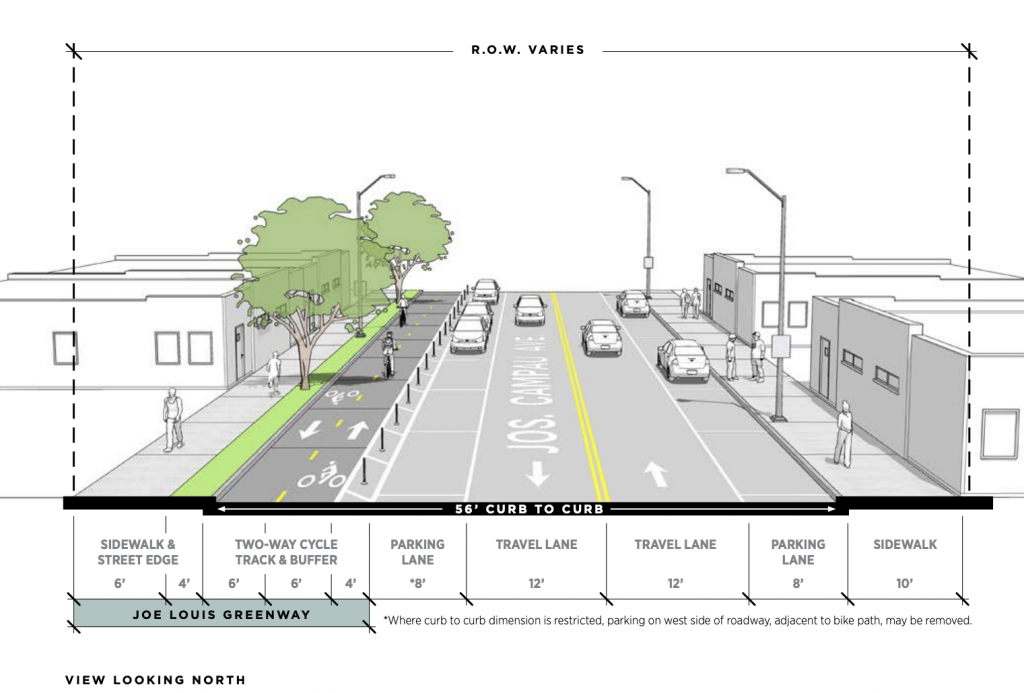

In the Joe Louis Greenway report, the term “real estate” is mentioned only a small handful of times. But while “housing” comes up quite frequently, the city doesn’t appear to have a comprehensive framework for how it is handling the question of proximal development. We certainly have lots of questions about design standards (how can we incentivize high-density development for developers?), affordability (density bonuses? eliminating parking minimums, in exchange for lower-percentage AMI rental units? affordability at 80% AMI refers to Metro Detroit AMI, and it really needs to be more like 20-40% AMI for Detroit proper), and economic development (how can we ensure that Detroiters get access to good jobs and job training instead of those jobs just going to, say, Joe Blow HVAC Inc. from Clarkston?).

if the city wants to use the Joe Louis Greenway as a major economic development tool, it will necessarily need a bunch of really robust frameworks to incentivize, finance, and guide the design of, building stuff within the corridor.

I’m trying to get some information from the city on this issue, because it’s kind of operative to the future success of the greenway.

Detroit: Low Density Vs. Everybody

Still, it’s not as though Detroit is likely to see an immediate boom in luxury housing on the West Side as the Joe Louis Greenway is completed. Minneapolis already had about 1.5x the population density of Detroit when it started building the greenway. The greenway also was already occupying space connecting a solidly upper-middle class neighborhood (Bde Maka Ska, formerly Lake Calhoun, and adjacent areas in the west), and the more mixed-income and middle class areas closer to the interstate and east of the interstate (see pics). In other words, there wasn’t the demand for Detroit to begin with. So if the city wants to use the Joe Louis Greenway as a major economic development tool, it will necessarily need a bunch of really robust frameworks to incentivize, finance, and guide the design of, building stuff within the corridor. Value capture, TOD, the whole bit. I’m hoping they have some ideas for this.

For my part, I’m all in on the YIMBY front. But I really would like to see some more specifics about how the city is going to manage the corridor development angle. Detroit can and should be the centerpoint of the national conversation on equitable redevelopment. Focusing on housing and real estate as part of this would be valuable– and hugely beneficial as part of the Joe Louis Greenway project.

The City of Detroit had not responded to multiple requests for comment as of the time of publication. Soren Jensen, director of the Midtown Greenway in Minneapolis, responded to a request for comment, and we will update with some more information in the coming weeks from a new report the organization will be releasing.