Lessons from Tampa: How Transit Funding Works

A bunch of people have asked me where transit funding comes from. Unsurprisingly, cost is the forefront in most conversations about infrastructure. Except, uh, roads– those are a God-given right. Anyway, I learned a lot at APTA in Tampa, wrote this up a long time ago, and promptly forgot about it, so here it is.

A BRIEF PRIMER

First off, capital expenditures are much easier than operations funding. This means you can buy a bus, but, to quote Han Solo, “who’s gonna fly it, kid?” Federal matching funds often will provide up to 80% of capital budgets– but up to only 50% of operating budgets. They’re also, well, matching funds. There are grants to build stuff, but they’re limited.

Capital availability is a problem in a society that values tax cuts to the rich and weapons of mass destruction that can’t fly right more than its own infrastructure. So it goes.

Thus, though, a large portion of transit funding comes from local taxation districts. Because transit is first and foremost a local thing, this usually happens on a citywide or countywide level rather than, say, a local assessment district tax for a downtown. Local assessment districts are used to fund things like stadium redevelopment (yuck) or libraries or, you know, restoring the old clock tower, or what have you.

Then the question becomes what taxation method should be used to fund it. There are differences in funding mechanisms based on who carries the most tax burden. Because state or local income taxes are not a common source of transit revenue, I’ve omitted mention of this.

SALES TAX

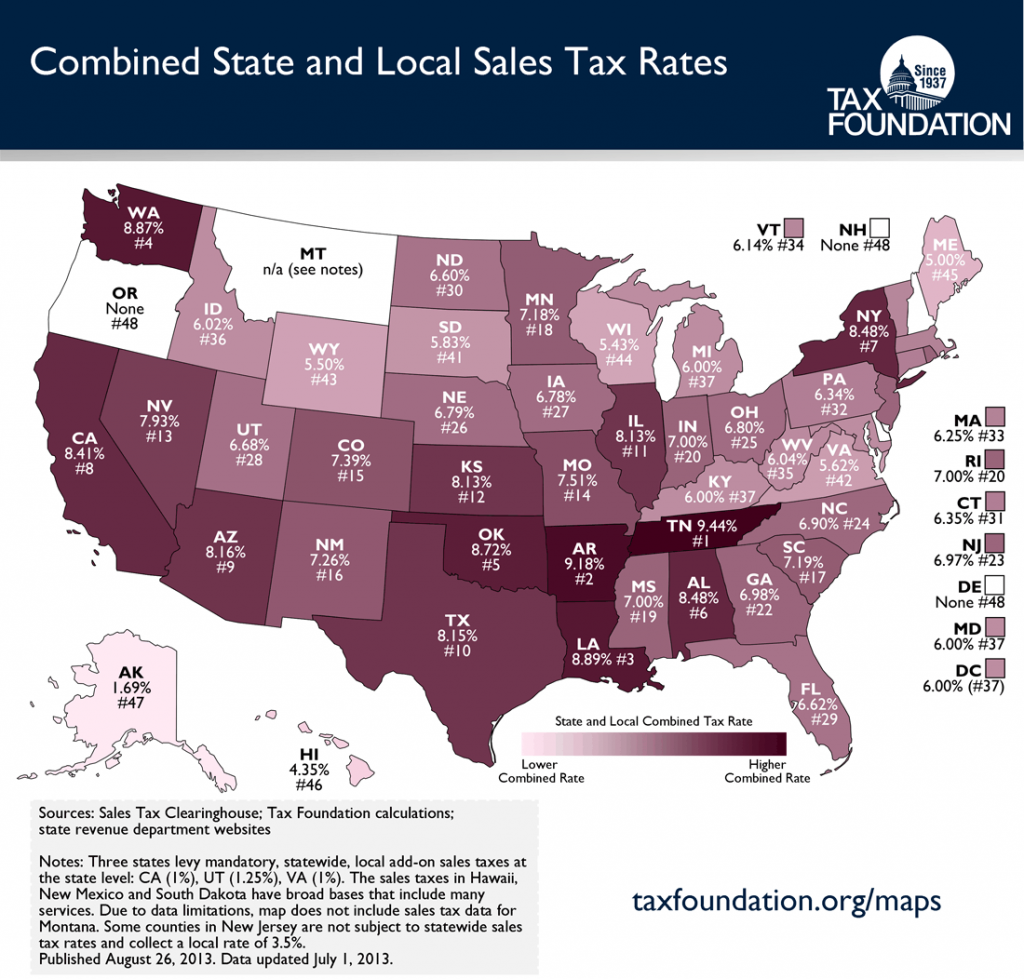

This is calculated at the point of retail transactions. Sales taxes are typically assessed on a statewide basis, and some states do not have sales taxes. But most states allow municipalities to assess their own local sales taxes as needed. Perhaps surprisingly (per the map below), sales tax rates by state do not really correspond to a “red state vs. blue state” dichotomy. Sales taxes are considered regressive because lower-income households spend a higher proportion of their income than wealthy households do. Florida communities like Hillsborough County (Tampa), however, favored sales tax for transit funding because of the high rate of tourist spending.

PROPERTY TAXES

This is what is proposed in Detroit through the RTA millage. Properties are assessed differently from state to state, but the idea is generally to tax some approximation or multiple of the property’s estimable value. Because governments move slowly and illiquid real estate markets move even slower, it is usually possible to do this over a long time frame without screwing over residents. The RTA would have added the equivalent of $3-5 per month per person per household for a three-person household for the average home, raising several billion dollars over 20 years.

FARE REVENUE

Most transit systems derive fare revenue, of course, which makes up as little as 0-5% (Paratransit and “Dial-A-Ride” on-demand services, for example) or more than 100% of costs (Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor).

USER FEES

User fees from non-transit sources can come from things like tolls, car registration, gas taxes, and more. They can be used to serve as a disincentive to But we know that highway trust funds and gas taxes are wholly inadequate to fund infrastructure maintenance, and certainly inadequate as sources of transit funding on their own. The federal gas tax was introduced in 1932 at a penny per gallon. It was last increased in 1993 to 18.4 cents per gallon. If it were indexed to inflation, the gas tax would be about 33 cents today. As the gas tax raised $26 billion in 2016 and demand for gas is not generally increasing even given low gas prices, we’re facing a massive deficit in infrastructure funding.

Forbes wrote that a widely supported hike would raise the better part of a trillion dollars by 2050. (I am extremely skeptical that we will be driving gas cars in 2050). Tax hikes are, of course, unpopular, and the proposed gas tax hike was mysteriously never explored further. Diverting money from things like car registration is thoroughly unpopular among tea party types and can be quite controversial.

I hope this explains a bit about how funding works for these systems.

(This article is part of a series on transit, mobility, and transit funding.)