A Mayor Should Create Value, Not Refinance The Lack Of It

Mike Duggan’s latest proposal to “eliminate blight” includes a proposed $250 million bond issue to finance his ongoing demolition program, which has run out of HUD Hardest-Hit funds. At issue is not the feasibility of the issue itself, but whether it will impose a cost increase on Detroiters. (Spoiler alert: It will. And that’s problematic given that we already have some crazy high property taxes.) There’s an alternative to this kind of thinking. But first, it’s important to understand how we got into this mess.

Duggan has long embraced the “demolition as community development” strategy. I’d say that this has been controversial owing to a number of public fiascos (more on this in a minute), but it’s less controversial than simply problematic and, uh, at odds with reality. One study several years ago demonstrated, through some clever manipulation of data, that demolition could increase real estate values, and since then, it’s been all the rage. Other studies have looked at the effects of blight removal on crime. It’s not rocket science to imagine that a block with burned-out buildings might be less appealing to prospective homebuyers than a block without burned-out buildings.

The notion of “demolition to increase value” is, however, fraught. The market in Detroit is a stark microcosm of the “missing middle” that plagues the national housing landscape at large. Demolition is not executed on an “as absolutely necessary” basis but rather where it is politically expedient. As a result, many homes are demolished that could be rehabbed for a reasonable amount of money. Duggan’s point is that every abandoned house must be demolished, which, given the tenuous ability to classify homes already in states of disrepair, occupied or not, is troublesome. Is the idea to turn Detroit into his native Livonia, density-wise? (I’ll return to this question in a bit.)

The job of figuring out which houses to demolish is hardly an enviable one. The low density of a city that has lost more than two thirds of its midcentury peak population forces policymakers to allocate scant resources (mostly to billionaires downtown, but that’s a separate article).

FUNDING DEMOLITION AS COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

There are a few problems with Detroit’s demolition program. First: The HUD Hardest-Hit Funds (HHF) were never intended to be used for demolition, but rather actual community development strategies in the wake of the 2008 collapse. Though it’s fair to argue that many of the demolished buildings did indeed need to come down as a matter of public safety, it is also fair to ask why so much has been allocated to demolition while funds focused on foreclosure prevention have been comparatively meager.

The Detroit Home Mortgage program, for example, was created to bridge the “appraisal gap” that exists between costs of construction and/or acquisition and the appraisal value that a bank will finance. Remember when those same appraisers justified sky-high valuations in 2004-2007? We didn’t forget! It’s a dumb problem to have to solve, but the program is a clever solution. DHM has unfortunately struggled with overall anemic loan volume in the city at large.

The Wells Fargo HomeLift program, which the company pitched as a “corporate social responsibility” initiative but was really part of a giant settlement for breaking the economy, was similarly quite limited in scope. I managed programs at Southwest Solutions funded in part by Chase Bank following a similar settlement.

Beyond these structural issues, Duggan’s programs have been plagued by scandal. Allegations of bid-rigging surrounded an ongoing FBI investigation. Contractors named their own price for backfill rather than bid it out, and could not verify the provenance of it, leading to questions about wholesale contamination, which was identified in a number of cases. A felon convicted of bid-rigging under the Kwame regime was caught working on a demolition contract. In a particular doozy, state representative’s house was demolished. Attorney Brian Farkas, who is sort of technocratic nobility and runs the demolition program through the public Detroit Building Authority, has brushed off concerns. Who cares where the dirt comes from, he asked, in fewer words.

Scandals aside, $250 million is, however you slice it, an awful lot of money. And if we’re being totally honest, there are better ways to spend that money. On, you know, things that might actually create value and tax revenue and jobs and actually effect development and investment. $250 million spent on demolition contractors means more taxpayer money leaving the city, since most of the demolition contractors are based in suburbs or owned by suburbanites.

What would that look like?

FUND NEIGHBORHOOD STABILIZATION THROUGH NEW DEVELOPMENT

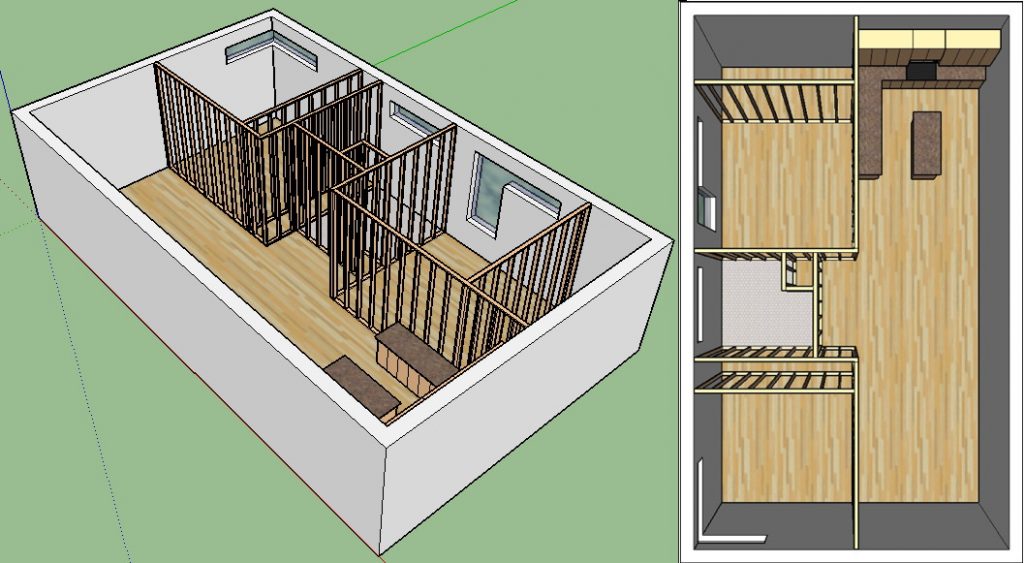

Why not put that money into the city’s affordable housing trust fund? A quarter of a billion dollars could subsidize the development of thousands of multifamily housing units and accompanying renovations.

Focus on the spokes of the commercial corridors: Jefferson and Fort. Michigan. Grand River. Woodward farther north from New Center. Van Dyke. Gratiot. Focus on the areas that have abundant and salvageable, multifamily architectural stock, in well-developed transit corridors, and have low valuations. Dexter-Linwood, Joy-Tireman. Pair it with a bad old TIF regimen in several targeted districts to improve surrounding infrastructure and you’re well on your way to a complete makeover of the key corridors in the city. It’d go a hell of a lot farther than the more micro-targeted, $35 million commitment Duggan previously made.

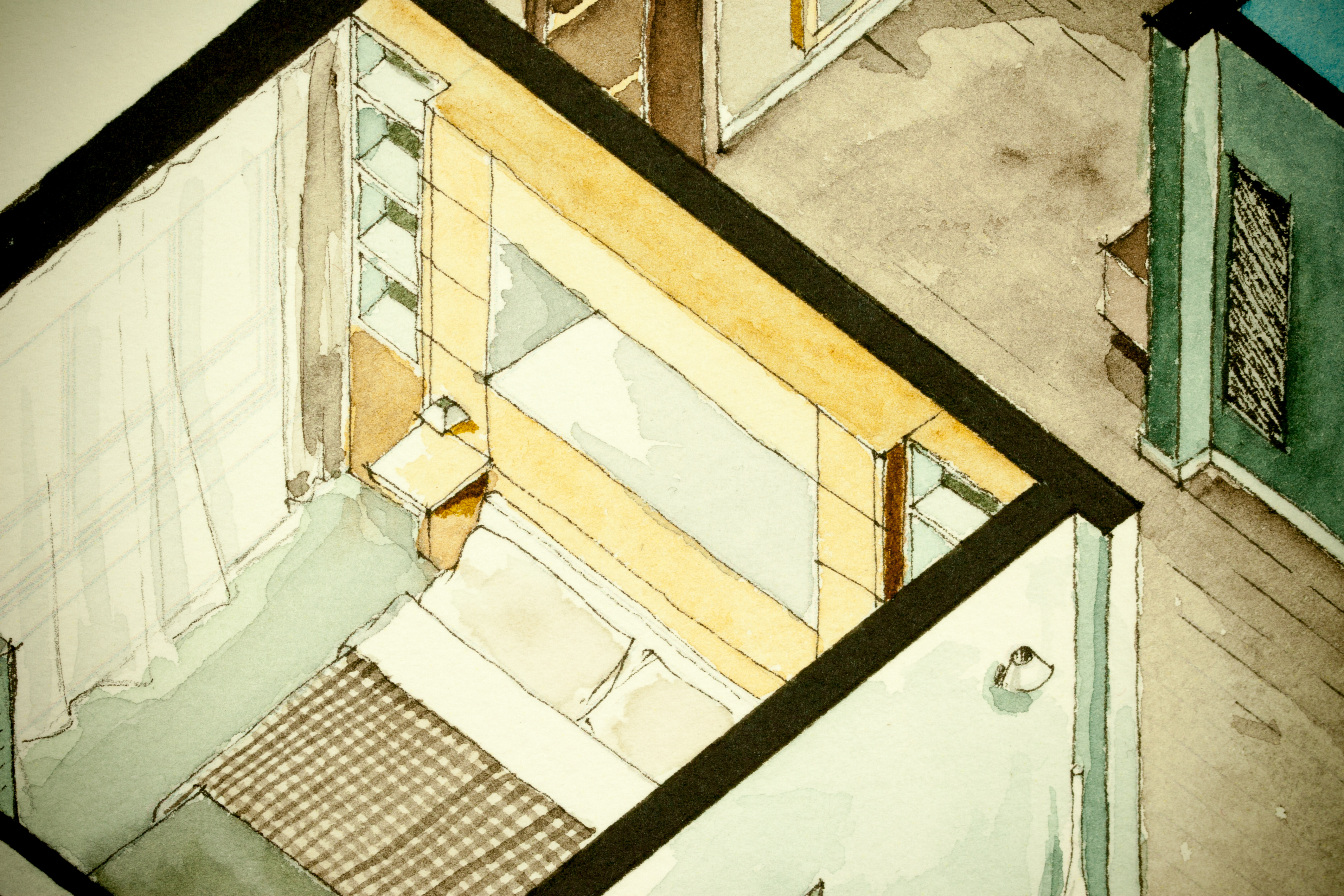

Let’s refer back to the rules of thumb that I, uh, so laboriously constructed for Detroit Park City. 872 square feet for an apartment at a cost of about $150,000 per unit. Land is more or less free if the city owns a lot of it and it is possible to acquire a bunch of cheap land along most of the major, formerly-commercial-but-not-anymore corridors. At these prices, you’re essentially subsidizing 1/3 of the cost of each unit, and that’s assuming it’s in the form of a grant rather than, say, a low-interest loan in a revolving fund.

A revolving fund could loan out this money at 0-5%, either operating at a net loss including administrative overhead or covering the bare minimum of operating overhead. A 5% annualized return on $250 million is more than enough money to cover administrative overhead, but not enough to cover the cost of capital, even in terms of inflation, so it would still effectively be sort of subsidy.

As it stands now, developers don’t develop four-story mixed-use buildings way the heck up Grand River Avenue. It’s not because of a lack of demand, it’s because of a lack of capital. Mezzanine debt in a market where commercial (bank) lending is scarce is essentially like building a building on a credit card. You cut down the cost of capital and you’re cutting down risk– and maybe more developers would be interested. Especially if the city did the leg work to get these projects started. A transit-oriented project at Livernois and Grand River? Replacing a hellscape of strip malls and fast food joints with some attractive density– but located in between some of the city’s most historic neighborhoods?

While some demolitions are certainly necessary, the pace at which Duggan has demanded the work take place means that contracts will be awarded, by and large, to large companies. Those large companies will be, by and large, based in the suburbs (or, in one case, in Chicago). Subsidizing development instead at least provides an opportunity to create more local employment opportunities. And it’s not a stretch to point out that the biggest players in the small to mid-range of development are local.

Well, a boy can dream.

OTHER SOLUTIONS: FIX TAX FORECLOSURE

Nancy Kaffer of the Free Press pointed out that while the city may be easily address the monstrous and widespread issue of poverty in the city, it can easily address the tax foreclosure crisis, that results directly in vacant and thereby blighted homes.

“We’re pouring our money into a bucket with a hole in it,” she said on Michigan Radio. “You can’t demo your way out of blight when you haven’t meaningfully addressed blight the causes of blight.”

Duggan’s administration, ever in its increasingly Trump-esque quest to evade public scrutiny, is pitching the bond issue as a thing so great that it does not need to be questioned. (Incidentally, the “ineffable solution” pitch– that we’ve got it all figured out, so don’t worry about it- is characteristic of Trump as well.)

Which is why it’s been ever more interesting to watch investigative reporter Violet Ikonomova square off with Duggan’s crew, as she did when she crashed a private breakfast hosted by Duggan to promote the bond issue. (John Roach in the mayor’s office doesn’t respond to my inquiries, or I’d try and get a quote from him on the story.)

One thing’s for sure– as a city taxpayer and property owner, I’m not excited about the idea of kicking a quarter-billion dollar can down any of the major arterial roads in the city. Kwame had a similar idea when Wall Street dragged him into the metastatic debt bubble of the 2000’s to refinance the city’s crippling debt load.

It didn’t end well for him.