Sorry, Tim– Pocket Change Can’t Fix Suburbia.

Apple just announced that it’s committing a bunch of money to housing development in the Bay Area. That’s good, right?! The principal element of the $2.5 billion package is a $1 billion line of credit. $1 billion will also be committed to a first-time homebuyer assistance fund. At a median home price of $966,000, that’s just over 5,100 downpayments of 20%. But housing experts suggest that the Bay Area is hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of units behind. $1.1 trillion market capitalization, 1 million housing units short, $5 billion investment. How do we make sense of all of this?

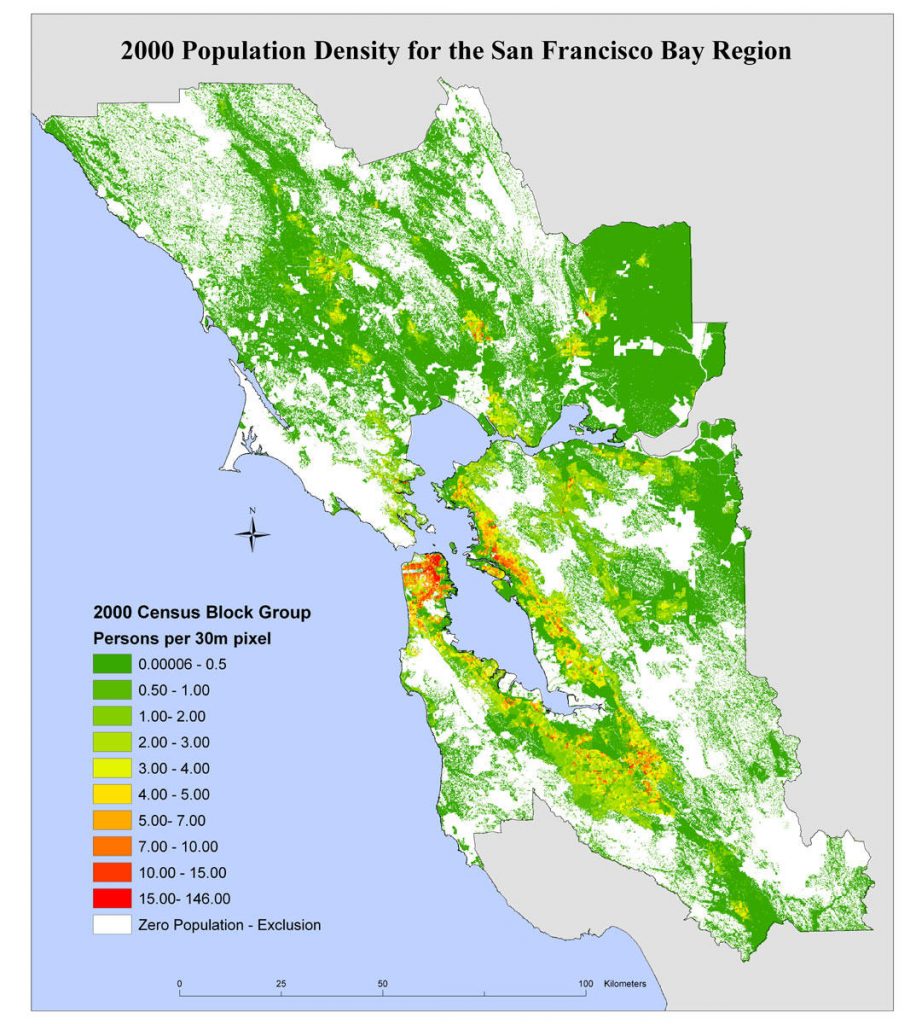

First, Apple is joining other clubs of tech behemoths based in the Bay Area to produce this, well, whatever it is. The Bay Area’s notorious housing shortage has made international headlines in recent years with the explosive growth of the current tech bubble. That companies like Google and Apple are based in low-density suburbs distant from the, uh, “authentic culture” of San Francisco means, well, a whole lot of messy. Google made a similar commitment to housing investment earlier this year.

EQUITY CONTRIBUTED IN-KIND IS NOT GOING TO FIX THE HOUSING MARKET

Of course, when you read closer, both companies’ commitments are heavily dependent upon their “contribution” including not hard cash, but equity in the form of land that they own. The actual cash being committed works out to well under one percentage point of each company’s cash reserves. That’s the best you’ve got, Tim?

Lest I seem ungrateful: Companies desperate to attract and retain talent are interested in spending less than 1% of their cash reserves on things that could make a substantive difference for millions of people while also making their employees and governments happier. Figures. When the market crashes and trillions of valuation are wiped out from tech, this will moderate housing demand: San Francisco’s race to the top has slowed considerably in recent months as the market tops out. But at issue principally is the structural limitations of housing investment in the Bay Area.

Democratic presidential hopeful Bernie Sanders points out that Apple’s commitment does not solve the structural problems with housing in that it turns Apple into a real estate lender. (As someone who did time in a home repair grant program, I can attest to the fact that it’s not an enviable role.) Sanders’ solution instead suggests that corporations pay their fare share of taxes. It’s a fair point, especially returning to this question of how these companies have amassed so much cash and can’t do anything with it.

Except, of course, share buybacks, which is going to turn out great in the next economic downturn. Also important is the fact that we can’t just wave a magic wand and rewrite the tax code– that will take years and I am increasingly doubtful that in my lifetime we will even have an equitable system that works for human beings as opposed to primarily for billionaires like Mark Zuckerberg, Tim Cook, Larries Page or Ellison, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, and those other heralded titans of industry, dreams, and magic.

But I digress.

Also fair is the observation that California’s urban development platform, is, well, messed up. While the state is in some regards a leader in regional thinking and planning given the sheer necessity of it, it is to some degree held hostage by Silicon Valley wealth.

HEY, BIG TECH: PUT UP OR SHUT UP

Nor is Apple exactly a champion of sustainable urbanism. The Bay Area, that great, burning center of the cosmos of innovation around which we all aspirationally orbit, has woefully underdeveloped public transit for how much it has grown in recent years. Apple has not been particularly helpful in facilitating a long-proposed (and long-delayed) BART expansion to San Jose. Tim Cook wants Apple to be in the spotlight for their purported housing commitment, yet Apple is holding up transit expansion. Funny how that works.

Critics have further pointed out– correctly- that California’s addiction to the single-passenger automobile is perhaps the greatest threat to its otherwise generally laudable sustainability goals. The embattled high-speed rail project and hard austerity proposals to eliminate transit funding are further hurdles to sustainable development.

Where is Big Tech in this debate?

With beaucoup bucks in cash and lobbying money, they should be front and center. Heck, Apple could fund a national high speed rail network out of its own cash reserves. But they won’t, because that doesn’t involve selling more widgets. Of course, Apple isn’t a railroad. But that these companies have exploded in growth means problems for the cities they’re located in. They are necessarily stakeholders and are necessarily crucial to the process.

REGIONALISM AND ZONING

Ars Technica’s Timothy Lee points out that restrictive zoning limits the effectiveness of the package. Lee focuses on the high percentage of zoning in the city of San Francisco dedicated to single-family housing and the higher percentage in the suburbs. But YIMBY’s in San Francisco frankly bark up the wrong tree by focusing disproportionately on the city itself. Tech immigrés flocked to the city because it had decent, vaguely reasonably-priced housing. You know where they didn’t have a lot of decent and affordable rental housing?

The ‘burbs, of course. The ‘burbs that remain low density in spite of desperate and ubiquitous demand to become denser.

Once we get into the billions of dollars, we’re moving a bit beyond gestural commitments. But the scale is different, too. And contribution of value principally through company-owned land will be dubious in the event of a real estate market crash. Lee’s article is right to point out the problem with zoning, because it allows wealthy cities like Mountain View or Palo Alto to retain their low-density, single-family exclusivity.

Communities can’t bill themselves as “livable” or “growing” if they, well, fight livability and growth. And yet.

Beyond the classist exclusivity of many suburban communities, the housing stock in the region is also generally just awful. The region’s population has nearly tripled since 1950, meaning that most housing has been built with automotive hegemony in mind. Cities like Mountain View or Sunnyvale didn’t appreciably exist before the midcentury. Build denser!

STATE VERSUS LOCAL INTERVENTION

For one or two million dollars in unrestricted grants and revolving funds, I was able to develop dozens of affordable housing units in Detroit. It’s a different market, sure. But it makes me think about how much could be done with more resources if the focus were to unapologetically build denser cities rather than to just make gestural, vague commitments to “affordability.” High density means that sky-high land acquisition costs amortize to a much more palatable per-unit cost.

Scott Wiener’s SB 50, which would force sweeping changes to zoning, has been tabled for at least a couple more months. New legislation does, however, make it easier to build accessory dwelling units, which is at least a start. What else could work? Absent a national housing policy, which is likely to only develop well after a Democrat takes office in 2021, local policymakers and electeds in cities like Cupertino could advance proposals without SB 50, valuable though it would be. Complex challenges require bold action. If “too little, too late” is the best that Big Tech can do to solve a pervasive housing crisis, local governments retains the ability to step in, exercise its constitutionally enshrined police power, and produce cities that work for human beings.