Liability in the Age of Easy, Profitable Destruction

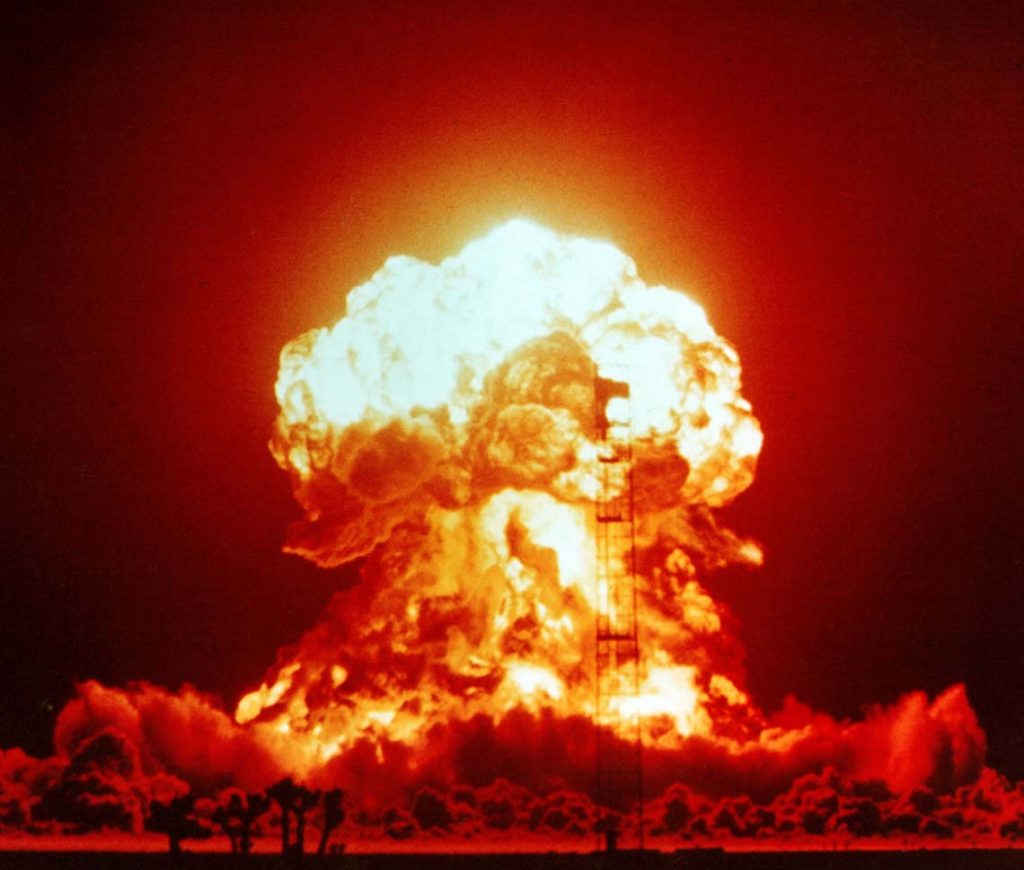

Early on the morning of July 16th, 1945, in the middle of an uninhabited desert halfway between the remote cities of Alamogordo and Soccoro, New Mexico, the first atomic bomb was detonated. It was the culmination of six years of work by over a hundred thousand military and civilian personnel from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada, in what became known as the legendary Manhattan Project.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist who led the project, later recalled words from the Bhagavad Gita, a line that Vishnu says to Arjuna: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” At the moment it was apparent that the test had succeeded, fellow physicist Kenneth Bainbridge turned to Oppenheimer and said, a bit less philosophically, “Now we’re all sons of bitches!” He later characterized the implosive fission of a roughly softball-sized pair of half-spheres of plutonium as a most “foul and awesome display.”

After cheering the development of this tool of mass destruction, Oppenheimer would later lament the use of the second atomic bomb against civilians in Nagasaki, in the second of two bombings that killed hundreds of thousands of mostly civilian Japanese. This would, according to accounts of an October 1945 meeting with President Harry Truman, really piss the president off. The argument in favor of the use of atomic bomb against civilian targets has been widely accepted by many historians as a horrific, however favorable, alternative to the millions of civilian and military deaths that would inevitably result from an invasion of Japan. Of course, plenty of historians still don’t agree that an invasion of Japan would have been the only way to force the country into surrender, especially given the fall of the Third Reich earlier in 1945, but that is, in this case, a separate can of worms.

This question of responsibility has long dogged scientists. Is a scientist responsible for what they create? In a liberal market economy, is a company responsible for what they create? It’s a funny point of agreement between liberals and conservatives that highlights the rise of a new American liberalism in the “neoliberal” camp– the insistent focus on the purity of the individual and of individual intent.

I frequently get into this debate with scientists who believe that their work is ethically and morally pure and that they don’t have any responsibility for what happens to the science after it leaves their hands (I seem to remember what actually devolved into a shouting match in the boxcar at Batch with a Canadian Ph.D. of a now-ex girlfriend, who argued that genetically modified organisms are pure and virtuous science, and scientists should never bear any responsibility for the malfeasance of their corporate overlords).

But the impending collapse of Purdue Pharmaceutical as a target of nationwide opioid lawsuits seems to demonstrate that, at least in the eyes of courts, companies indeed do have responsibility for what they produce. The company has been hammered by opioid lawsuits owing to the international epidemic of overdose deaths and has agreed to a settlement that pays out way more than it actually makes, meaning, well, deuces. Beyond Purdue’s five thousand worldwide employees, this settlement, as it continues to unfold, will invariably have massive repercussions and implications for the trillion-dollar pharmaceutical industry as the 1998 tobacco settlement did for that industry.

Courts– and society- agreed in 1998 that Big Tobacco was liable for selling products that killed millions. That settlement, which generated billions in revenues for states, tectonically restructured the tobacco industry, but it certainly did not destroy it. Tobacco remains a cash cow, with an albeit smaller pool of companies still churning out revenues (see table below). The major thing differentiating the multi-billion dollar development of a weapon of war like the atomic bomb from the private sector development of tools of awesome and lethal power is that the government has effectively limitless resources at its disposal and so the motive for massive scale is that more salient.

The major thing that differentiates my point of view from the modern American conservative or the Ayn Rand-reading neoliberal pedant is my belief that the burden of responsibility should fall upon those with the most power, the most control of the value chain, and the most influence. This has differentiated me in my characterization of a lot of conflicts. “Maybe Eric Garner shouldn’t have been selling cigarettes if he didn’t want to be extrajudicially executed!” they will say, or, “maybe that Palestinian teen shouldn’t have been throwing rocks at a tank if he didn’t want to be shot!” So, no, I do hold the radical belief that if you have more power, more information, and, usually, more capital, that you have more responsibility. Not tobacco farmers, nor the workers who run the massive ships that bring oil across the oceans, but, indeed, doctors overprescribing opioids– probably not only violating the Hippocratic oath but also fit in the same category as extremely well-paid, extremely well-informed corporate executives.

Big oil and big tobacco have one unusual thing in common that makes them both attractive investments but also particularly easy targets for litigation over the collateral and externalized effects of their products, and that’s the fact that they generate a ton of cash that the companies don’t know what to do with. The average company in the S&P 500 pays a dividend of 2.5%, but tobacco and oil companies routinely pay out two or three times that rate. In business terms, it’s because they have a good thing going, they’re selling a lot of it, and if they were to keep that profit, they wouldn’t necessarily be able to deliver as good a return on equity as selling barrels of oil or smokes. Similarly, tobacco companies will not diversify into manufacturing iPhones– though it is possible to imagine a world where oil diversifies into energy products like batteries or solar panels (remember the short-lived Beyond Petroleum?), but for now, the name of the game is to stick to cranking out that sticky icky.

| Company – Oil | Cap | Yield |

| BP | $126bn | 6.57% |

| Chevron | $224bn | 4.03% |

| EcoPetrol | $689bn | 8.27% |

| ExxonMobil | $300bn | 4.91% |

| Royal Dutch Shell | $224bn | 6.76% |

| Total SA | $135bn | 5.77% |

| Company – Tobacco | ||

| Altria | $82bn | 7.66% |

| British American Tobacco | $82bn | 7.29% |

| Philip Morris | $113bn | 6.24% |

Pharmaceutical companies are a bit different because they ride on the prospective success of single products that have massive R&D costs, but end up being massively profitable before their patent expirations. They generate massive amounts of cash but often do not pay dividends– they are sort of the sectoral equivalent of tech unicorns that VC investors are often hunting. Everything hinges on the success of FDA approvals, drug trials, and the ability to commercialize these very valuable patents until they inevitably expire. The company that first announces that it has developed a cure for cancer that can be commercialized is going to go through the roof overnight in terms of valuation.

Granted, part of this is just tradition of how companies in different sectors are managed and how capital assets are organized. But the major difference with the Sackler Oxycontin Empire is the fact that opioids were treated the same way by the company as oil was treated by ExxonMobil or tobacco leaves by RJ Reynolds or Altria.

Beyond big pharma, this question of liability in the form of externalized damages opens up avenues toward litigation that could transform entire industries and, indeed, society at large in how we think about the very notion of personal and collective responsibility. I’m not alone in thinking about this question, and it’s interesting to consider the biggest potential targets in terms of the deaths and destruction they cause every year:

1) Big Oil: This seems the biggest target, given the tremendous damage to air quality, locally, and to the planet’s climate, by combustion of gasoline. Lawsuits are already ongoing against ExxonMobil and others, and the oil industry is responding by slowly getting its feet wet in some nascent technologies that, it claims, will mitigate climate change. While some lawsuits against big oil have been dismissed, others are proceeding.

2) Tobacco (again; still nearly half a million deaths per year in the US): Media coverage has focused heavily on a spate of incidents involving bizarre respiratory illnesses of otherwise healthy people using vape pens. Tobacco makers are all deep in the vape game at this point, and, as we explore alternatives to tobacco in terms of synthetic vapor products and cannabis, the question of intensive standardization and regulation will become ever-present– but likely not before some major litigation points out the complete lack of controls that have led to these deaths.

3) Automakers (36,000 killed in car crashes; 6,000+ pedestrians killed and 800+ cyclists per year): The uptick in pedestrian and cyclist fatality rates is not purely a product of the increase in automakers’ insistence on selling trucks and SUV’s. But that is a huge part of it. Of course, automakers would be free to use the defense that they aren’t driving the cars that are killing people, or that cities are designing streets poorly (they are). But it seems they are certainly aggressively selling cars that they know to be more lethal in collisions with pedestrians, and that is troubling.

4) Gunmakers (21,000 suicides, 11,000 homicides annually): The firearm industry is already in freefall since that gun-grabbing Muslim socialist Obama left office with nary a meaningful piece of firearm legislation to his name. I wrote about this a year and half ago, when some major funds decided that they were dumping gun stocks (a little late, given that this was after they had substantially declined). Since that time, leaders VSTO, AOBC, and RGR have all lost a further 20-70% of their valuation. Congress under the Bush Administration tried to protect the gun industry from litigation. But the aftermath of the 2012 Sandy Hook massacre provided evidence that the victims or families of victims of shootings are entitled to sue manufacturers. At issue is the same question of negligently or even criminally pushing sales with no attention to ensuring safe usage.

This collective batch of companies comprise multiple sectors that represent, depending on how you count, double digit percentage points of the entire US economy or, indeed, global GDP. But what we should have learned from “winning” the war on coal is that markets actually do work in cases when they’re allowed to, and can indeed replace bad things with better things that do better for everyone. Just to be clear, I’m not saying that capitalism doesn’t still need to be reworked from the bottom up, but rather that it’s not as though going after the major offenders is going to result in some sort of cataclysm, as is the scenario painted by sundry hand-wringers of the right wing media echo chamber.

The Sackler family is already trying to disclaim responsibility for the monster they created, but it’s a little late for their business empire. But in comparison to Purdue’s private ownership, public companies may receive no such protection if litigation proceeds against the likes of every household ticker symbol on the stock market involved in the manufacture of various and sundry tools of death and destruction. It is below us as a human race, whether technicians or managers, to not connect the dots between the products we produce with our own two hands and what is done with those products.