Whomst Should Bear The Cost? Mobility and the Workplace

I figured I could kick off Detroit Mobility Week with some exploration of a debate currently simmering in my office over the term, used in reference to employment, “must have access to reliable transportation.” The term is used by HR professionals to ensure that interviewers don’t ask prospective employees whether they own a car, which is usually not allowed in employment law. “Reliable transportation” could therefore be a bus, a bicycle, or, in the case of that famous Detroiter who walked five hundred miles and walked five hundred more just to get to his nine-to-five, a pair of feets.

Or so I thought.

On my first day of the new gig, I was called into the principal’s office.

“I’ve been doing this for 20 years,” the baffled assistant director explained, “and I’ve never had someone hired who didn’t own a car.”

In a city where a quarter of the households don’t own vehicles— three times the national average- no city inspector had, in recent memory, been hired without one. I told him that I had a valid driver’s license with no points, nor doubts that I would be able to fulfill the requirements of the job. I had access to a car (typically GM’s own Maven carshare, which, apart from a monstrously annoying Android app, is actually super convenient).

I was then called into HR. They were similarly miffed. The abbreviated version of a ten minute conversation that ended with me filling out a form that says that I have a car I can use.

“In the interview, you told us you had a car,” one HR person said.

“I didn’t. I said I had access to reliable transportation and a valid drivers license.”

“Fair enough,” they said, more or less. I remembered the interview quite well. They had asked me whether I had parked in the Larned Street garage. I would not spend the money for the garage for an interview so close to my house– I had taken a MoGo bike and rode the bus home.

Back at my desk, professional reality sets in: Approximately five days a week, I am told, I will need to be doing site visits– inspections of property under development, vacant property, and rental property, mostly falling under the mayor’s new initiative to improve the availability of good housing stock by ensuring that rental units are well-maintained, and to incentivize maintenance of vacant lots. Though this wasn’t exactly the professional direction I saw myself taking, I wrote about why this was important many moons before I took the job with the city.

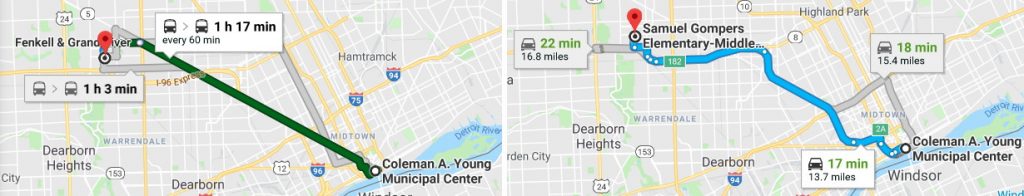

So, site-to-site, year-round. A regular bike won’t work, and the bus definitely won’t work (see below). So, everyone tells me, I need to get a car. It’s the Motor City, they say, thumbing their noses at Detroit’s rich history of bicycles and public transit that deteriorated with the city’s economy in the mid to late 20th century.

Upon seeing my bike helmet and gear, the typical response from my colleagues, who are mostly men in their 50’s and 60’s, is a slightly bemused but reasonably good-natured laughter. I’ve often worked in office environments that find it endearing that this cute hipster rides his bike to work. I grew up in a compact city riding a bike around town with parents who both rode bikes to work or, in my dad’s case in the 80’s and early 90’s, rode to the train station (Intermodal Before It Was Cool). It was cheaper. Parking was rough and often expensive. Exercise is good for you. The list goes on.

But plenty of people ride bikes in the hood, too, and in Detroit, this is a widely prevalent mobility solution for people who can’t afford the outrageous insurance premiums and need more flexibility than is offered by the infrequent DDOT routes. When a right-wing gubernatorial candidate says that he’s probably going to get on board with Detroit’s Democrat mayor in a lawsuit over insurance, that’s when you know times is hard.

Last year, I ditched my car because I didn’t need one. That, and I got in a pretty nasty car accident, the victim of a hit-and-run, that left me $9,000 poorer and with absolutely no interest to again spend that much more money on an extremely expensive piece of equipment that I only used once a week. I was mostly okay, physically, but seriously shaken up. I was also pissed off at Progressive and the Detroit Police, who first accused me of fleeing the scene of an accident that I hadn’t caused (because it took them hours to show up and so I walked home and went to bed), and then accused me of causing the accident, but only after ultimately failing to retrieve any video footage.

I had bought the car because my last job had told me I needed one to drive around town, period. Yes, Nat, it’s cute that you ride your bike to work, but we can’t afford to furnish a vehicle. They never ended up settling mileage reimbursements in a timely fashion, and, in my Amortization Of All The Things spreadsheet (don’t judge me), I reckoned that this automobile cost me an average of $31.60 per day for its short lifespan of a year. $11,534 represented 26% of my annual salary.

There was $8,000 down the drain, plus the $1,900 in insurance I had paid, $750 in registration fees, plus $250 after the accident to a towing company that is mysteriously owned by ex Detroit city cops who tote .45’s and accept payment in cash only and can’t be found in Google Maps or public directories (sketchy? never!). I couldn’t afford the $400 a month that Progressive, Geico, or AAA wanted to insure the car with the collision coverage that would have reimbursed me for the whopping $9,000 repair tab I got quoted.

Over the next year, even though I wasn’t making much money, I managed to save– because I wasn’t spending a grand a month on a car. I upgraded my bikes, got a winter bike set up, and bought a needlessly fancy used road bike. And still saved money.

It’s ultimately about cost. In the at-will employment hell of an economy that we live in, workers have few rights, and cash-strapped employers can’t afford to provide fleet vehicles, so they simply push that cost onto the employee.

I am not spending much time weighing into why that isn’t fair. We already allow highway infrastructure, congestion, car accidents, and pollution from cars to cost several hundred billion if not into the trillions of dollars per year– who cares if employees are inconvenienced to the tune of 25-40% of their salaries?

Is it feasible for me? I looked at a few options.

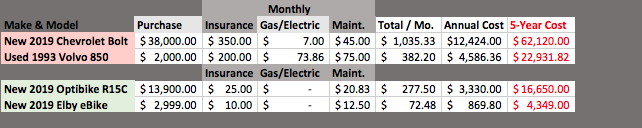

OPTION 1: A NEW, DETROIT-MADE, ELECTRIC CAR

At the most extreme high end, I look at buying a new electric car, thinking about fossil fuels, Demonstrating to Mr. Market That There is Demand For This Product, and saving a baby seal, whatever. (They’re also assembled in Hamtramck and Metro Detroit!). But Chevrolet prices its albeit well-reviewed electric cars, the Volt and the Bolt, in the stratosphere, to account for the $7,500 tax credit. The margins are therefore way– and unnecessarily higher (and they’re wondering why on earth sales have plummeted). $38,000 for a car that should cost– magically, minus the tax credit- $30,500? Financed, that’s about $750 over five or six years, depending on what rate you get. Insurance in Michigan will run you a few hundred a month– maybe $350 or $450. We’re already at almost $1100 a month now– comparable to the short-lived Prius C.

OPTION 2: THE SPORTS UTILITY JALOPY

Not a problem, my folks say, you can buy our 1993 Volvo 850 if you want. With a Kelley Blue Book of $1,750, it still costs $200 a month to insure. Gas would be exorbitant for a vehicle that gets a maximum of 26 miles to the gallon on a good day and whose exhaust smells like a mildewy paint spray booth until the engine warms up. Not a win, no matter how you slice it. But there are other pros, including that it has heated leather seats, a sunroof, and I could fill it up with as much scrap copper as I wanted, while being a trendy northeastern dad in the 90’s and playing Pavement on the tape deck (!).

OPTION 3: THE VINTAGE TRENDSETTER

Not a problem, my plumber says, you can buy my Buick Reatta, a cocaine-in-the-80’s-white sportscar of yesteryear that featured a touchscreen and the legendary Buick 3800 engine. Older car will be cheap to insure, right? Nope– same minimum of $200 a month, plus the lower mileage. Same story. Silver lining is that I could wear my vintage red leather jacket and rock the Joe Keery As Steve Harrington In Stranger Things hair.

But, seriously. All three of these options translate to externalized cost for something that the employer is counting on me providing for myself. The starting wages of a city building inspector sat in the 30’s and 40’s from the 1990’s until the past year or so, when they were inflation-adjusted to the low 60’s. I figure that a car costs $9-12,000 a year including purchase, maintenance, depreciation, gas, and insurance, roughly in line with AAA’s estimates and controlling for Michigan’s sky-high insurance rates.

I’m supposed to sacrifice 14% of my pretax takehome– or as much as 23% of my aftertax takehome- for an ungainly, polluting piece of machinery that I won’t use outside half of the workday, possibly as few as three or four days per week? Simply because our system of employment is at-will?

I’ve since thrown out all of these options, deciding that I can, in fact, handle the job without the car. The little guy on my shoulder, the collective hundred-some-thousand-strong Facebook group known as the New Urbanist Memes for Transit Oriented Teens, has convinced me to push for a solution that involves a pair of wheels rather than four wheels.

I’m assuming that for longer distances that require faster trips, I can’t use my 1985 Panasonic DX3000, a heavy, beater of a bike, which has cost me probably $1000 over the past ten years and thousands of miles (1-2% of the cost of owning a car and it can go most of the places a car can go).

So I looked into eBikes that are suited to riding, street legal, up to 28mph, and can handle weather. At the highest end, I looked at the OptiBike R15C, which costs $13,900 and is basically an electric dirt bike, and at the lower end, I looked at the Elby 9-speed for an affordable $2,999, respectively US-made and Canadian-made.

Both can go a steady, street-legal 28mph for at least the length of an inspector’s daily route. Both have removable batteries that can be charged at my desk at work (no gas costs). Combine with a city-subsidized DDOT monthly pass that allows me to speed around the city with the courteous, comfortable service of the transit agency for less than the daily cost of my owning a car, here’s what I end up with:

Note that while I’ve calculated this on a five-year horizon and have assumed a lower cost of operation for the new Chevrolet, it seems likely that I would burn through some percentage of the permanently installed battery capacity within those five years. GM says this isn’t likely, and, to be fair, my Honda Civic Hybrid lasted almost a decade before its hybrid battery crapped out. But if it does, it’s supposed to be about $15,000 to replace.

The kicker here is that I could buy what is probably among the top five fanciest electric bikes on the market as well as a more, ahem, proletariat model, and still save money over five years versus the cheapest car option of driving Option 2, the Sports Utility Jalopy. If the Sports Utility Jalopy even makes it five years, which seems unlikely, as it’d be 30 years old, more than three times the average lifespan of a car in today’s day and age. Comparing lifespans, my bikes include the Panasonic (33 years old), a 1998 Trek road bike (20 years old), a Trek mountain bike (10 years old), and a Raleigh CX bike, a 2013 model that has thousands of miles on it and has had no maintenance issues.

I’ve determined that the ebike option is both preferable in terms of cost and in terms of not being beholden to a terrible, broken, and ultimately extremely expensive paradigm of mobility. Supplemented with affordable car share if necessary, I am 100% committed to exceeding the requirements of the job without owning a car. I’m also interested in demonstrating that it’s a win for both me and for the city (which then saves money on mileage reimbursements, which could be worth up to 5% of my pretax salary).

So, toward new paradigms of mobility– paradigms Metro Detroit and the Duggan Administration have indicated their strong commitment to discovering.

And I will keep my loyal readers posted.

My opinions and comments are my own and do not in any way represent the positions of the Duggan Administration or the Buildings, Safety, Engineering, and Environmental Department of the City of Detroit.