Detroit Tries On Form-Based Code in Brush Park

On Tuesday I attended a two-hour session at the MSU Detroit Center on Woodward Avenue in Midtown about the proposed implementation of form-based code in Brush Park, a neighbourhood just north of downtown where just this past week construction broke ground on the City Modern project, which will bring 410 units to a block and a half in the center of the district. The project is the largest residential district development currently going on in the city, followed by the 270-some units in McCormack Baron Salazar’s Orleans Landing, which just started leasing.

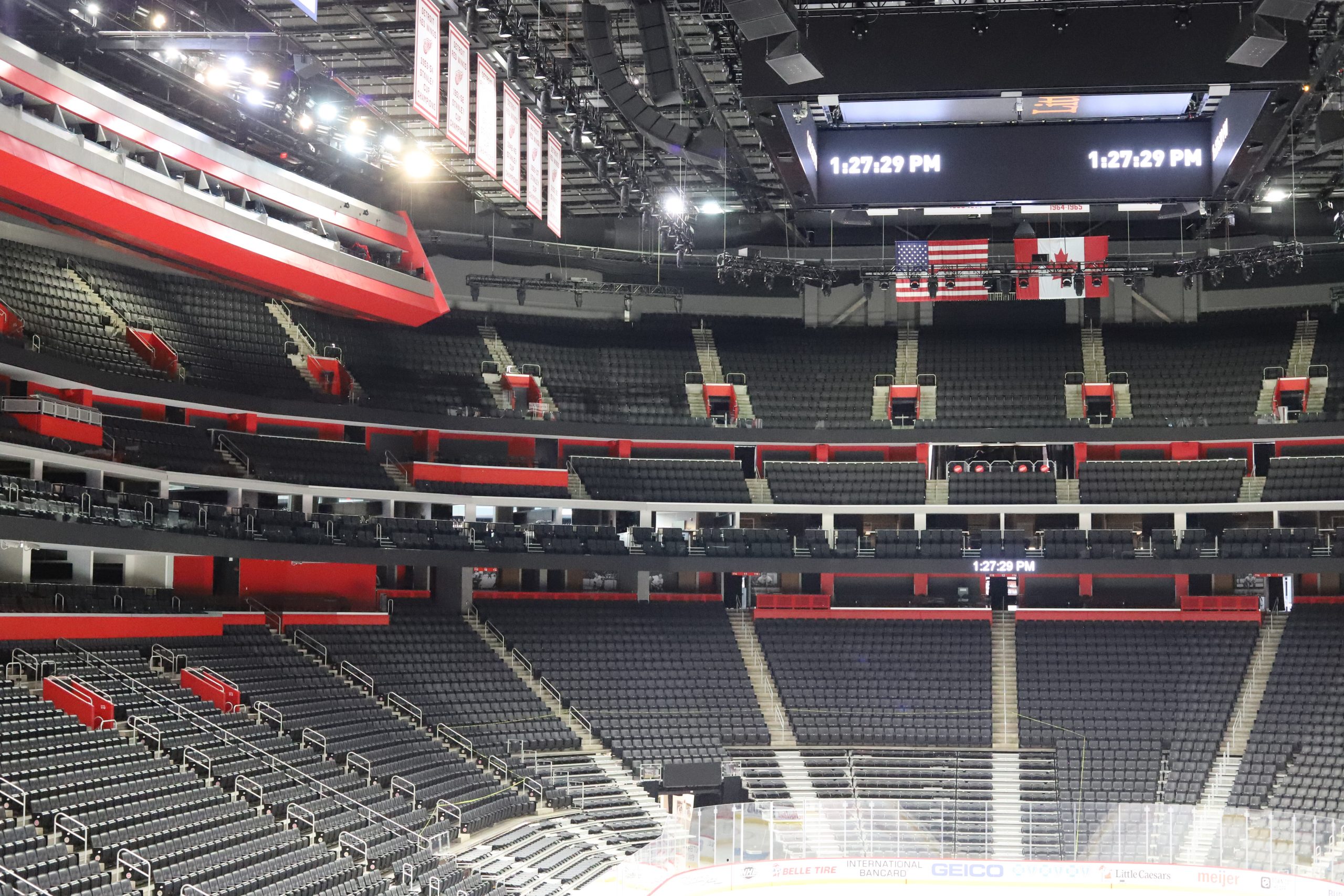

The City of Detroit’s Planning and Development Department (PDD) is implementing the new code in the roughly 180-acre (73 ha), 22-block area, from central arterial Woodward Avenue on the west to I-75 on the east, and from Mack Avenue on the north to I-75 on the south, in conjunction with Detroit-based Hamilton Anderson Architects and Boston-based Utile.

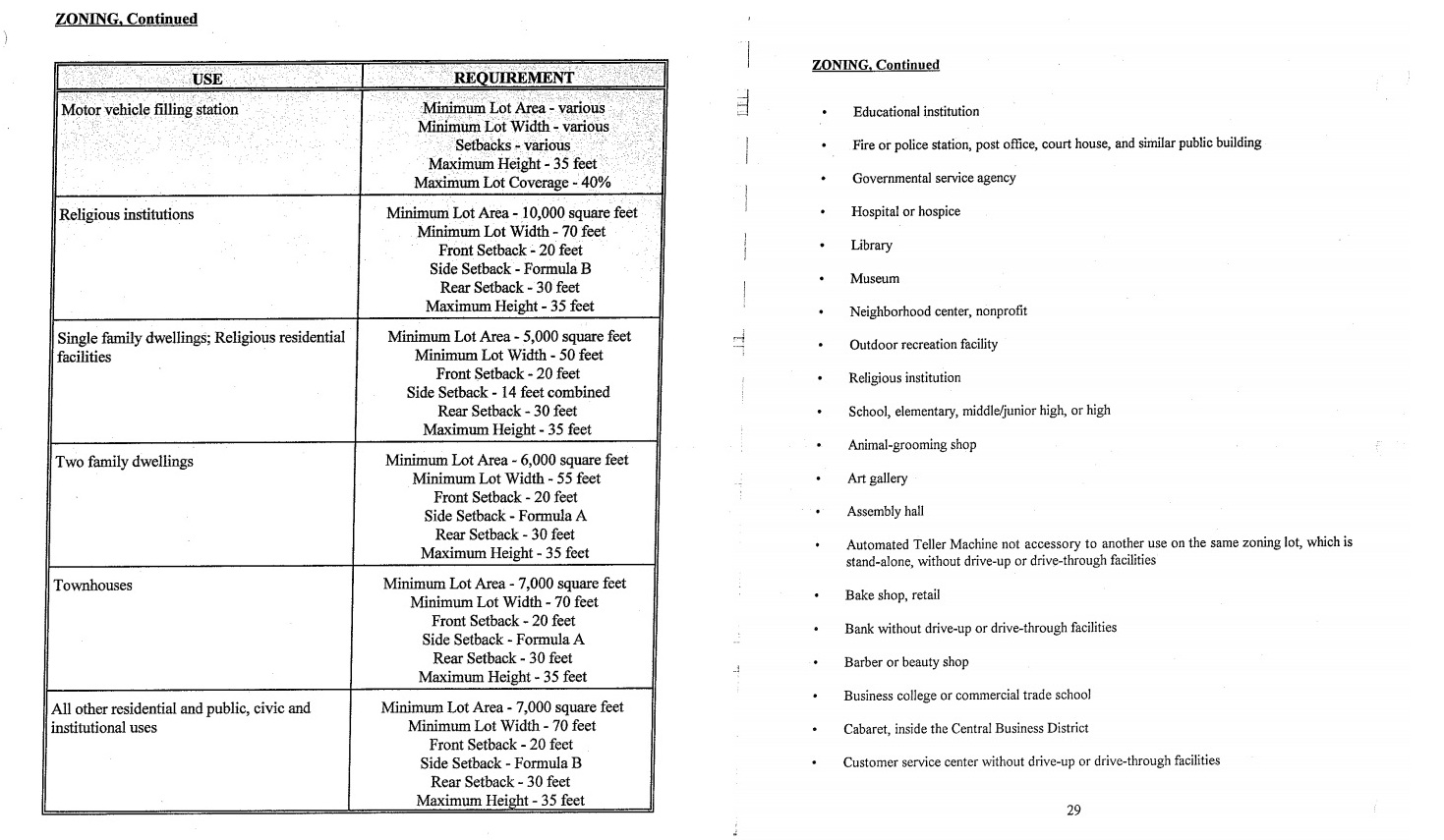

To those unfamiliar with comparisons between form-based code and use-based, conventional, or Euclidean zoning (named for Euclid, Ohio), form-based code is a newer regulatory framework that guides design principles for neighbourhoods as opposed to uses, while conventional zoning code restricts or guides uses, first and foremost, and regulates form as a secondary guideline, but typically weakly and still typically based on use. In 2009, I did a study of a neighbourhood in North Philadelphia, and found that the city was at that time battling with form-based code itself– to simplify the 56 zoning classifications that it currently had. Some of them had been designed specifically to suit types of development that didn’t exist when the zoning code was designed (basically a classification for “strip mall”).

I’ve found that regulation tends to become sluggish when it doesn’t undergo periodic reform. Below is a couple of pages from the B4 classification which says what you can and can’t build and which setbacks apply to which types (you can build a 35-foot tall Motor Vehicle Filling Station but you can’t build a 60-foot apartment building with first floor storefronts). Conventional zoning can be a very “Simon Didn’t Say” kind of approach to regulation.

The general idea of form-based is to encourage diverse uses of space, encourage mixed-use development (which can be cumbersome in some jurisdictions– remember my piece on East Chicago which referred to the poor guy who had to get a variance to open a barbershop in a commercial building), and make sure that the design of buildings in a specific district fit some sort of general standard.

This idea is fundamentally pretty old, but its implementation by municipal governments is relatively new. Cities have always existed, but city planning and especially urban design are very new things; Haussman’s renovation of Paris (1853-1870), for example, or Franz Joseph I’s nearly simultaneous, monumental development of the Ringstraße in Vienna (1857-1865) are massive examples of the implementation of district-wide redevelopment (development) that focused specifically on consistency in design standards and architectural form. But I digress– form-based code in its modern conception is a post-1970’s-everything-getting-critically-dismantled-era reform.

Form-based code in Detroit is an attempt at not only regulatory reform but also an attempt at smart redevelopment. Similar to how Detroit Future City explored the idea of long-term districts, somewhat more vague than the form-based code typologies, or how the 7.2 report looked at a specific geography to encourage and analyze development in the urban core, form-based code attempts to create a vision based on district-wide thinking as opposed to conventional, lot-by-lot thinking, which has successfully developed plenty of lots but often failed to encourage neighbourhood development on a larger scale.

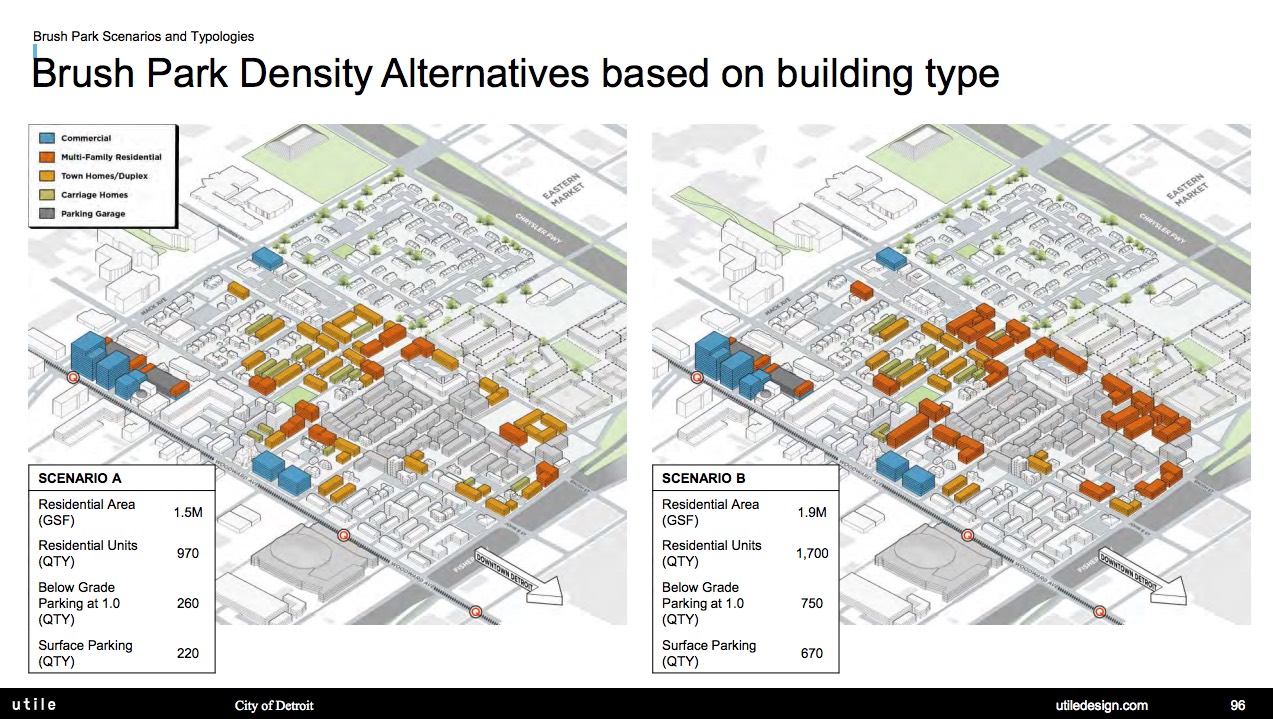

Attendees were concerned about a few things. A couple of folks said it sounded as though the proposal was to increase the density as much as possible (I’m very into that). Maurice Cox pointed out to one woman who complained about the prospective of limited parking (you don’t say!) that we often forget that Detroit’s historical population density, when the city was considered to be at its peak, with all of its buildings intact, was two or three times what it is now. It’s often true that we forget about that. In case of the City Modern project, adding 1.75 residents per unit would increase the neighbourhood density by over 2,500 people per square mile (50% over the Detroit city average), or, based on the figures below, an increase in density of 7,800 people per square mile.

I would love to see the blue blocks in the above image focus on development along Woodward– building ten or twenty story buildings- but I think that is a bit unlikely at this point. Maybe if the QLine/M1 Rail is a smash hit, it will encourage the city to adopt density bonuses similar to those in Chicago’s TOD ordinance. (Heck, I haven’t driven my car hardly at all since it got warm– maybe they’ll put a streetcar down Michigan Avenue!)

Make no mistake: It is possible that form-based codes can become as monstrously complicated and bureaucratic as conventional zoning codes (they cited Los Angeles’ new form-based code, which is very, very, very long), but the general idea of a form-based code encourages city planners to work with developers and residents toward a district-wide vision, say, broader than a single lot, and based on the idea that cities can be built based on encouraging general form rather than restricting oddly specific uses of spaces.

I am looking forward to seeing what CityModern brings– and hopefully much more development (and zoning reform) to come.