There Is No Public Transit Across One Of The Busiest Border Crossings In The World And That’s Kind Of Problematic

The corner of Wyandotte Avenue West and Patricia Road in the west end of Windsor, Ontario, is an odd nexus, a literal and figurative intersection between residence, commerce, international exchange, and industry. A 7/11 serves a motley crew of patrons at all hours, not the least of which are a global assortment of university students. On the way out, I hold the door for a young woman wearing a hijab and cross in front of a Chinese couple in a silver Toyota in the parking lot.

The corner of Wyandotte Avenue West and Patricia Road in the west end of Windsor, Ontario, is an odd nexus, a literal and figurative intersection between residence, commerce, international exchange, and industry. A 7/11 serves a motley crew of patrons at all hours, not the least of which are a global assortment of university students. On the way out, I hold the door for a young woman wearing a hijab and cross in front of a Chinese couple in a silver Toyota in the parking lot.

But I’m not here for late night fried food. I’ve already enjoyed my weekly– likely beyond weekly- calorie quota from my Monday night trivia session at the old Victoria Tavern on Chilver Road in Windsor’s Walkerville neighborhood, a few kilometers to the east across town. Rather, I’m actually waiting for a cab to take me home across the Ambassador Bridge, the privately owned border crossing that connects Detroit and Windsor.

And now, it’s time to head home. But how?

“Hi, Nash,” a text message flashes on my cracked phone screen. “Your driver is on the way. You can now track your Vets Cab number 24 by clicking here […]”

Nash, huh? That’s a new one.

Why am I taking a cab across the border?

For TheHUB, I’ve been working on a stakeholder engagement survey that delves into the regional transit question currently dogging Metro Detroit. I want to understand exactly why we have such an underdeveloped transit infrastructure. I wan’t to understand why it’s so hard for us to get things done as a region. I am not from these parts, as one might say. My understanding of “normal” was being able to take a bus to the train station and having my pick of ten Amtrak trains in either direction per day.

Not so in Detroit, where the Amtrak crawls the 40 miles to Ann Arbor in just under an hour. “It’s the Motor City,” goes the common refrain. “What do you expect?”

TWO MOTOR CITIES

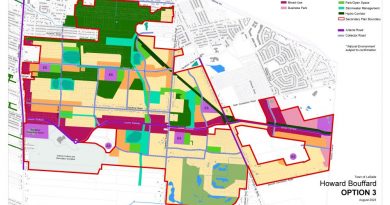

Like Detroit, Windsor, the Other Motor City, embraces a heavily automotive paradigm. But while Windsor boasts some excellent amenities– cultural diversity, a vibrant, increasingly diversified economy, and a world class food scene, to boot- it lags in progressive thinking about how to move into the next generation of mobility. While Detroit debates just how aggressive it should be getting about its new complete streets initiative, debates rage in Windsor over how to spend limited city funds to create more parking in the dense downtown, as though the availability of widespread, free parking is the make-or-break determinant of a vibrant economy (spoiler alert: it’s not).

Though Windsor is smaller than Detroit, the two cities are twinned in an important economic symbiosis surrounding, at least historically, the automotive sector. Jobs in one city are necessarily dependent upon the other, and this goes well beyond the city limits through the whole Great Lakes manufacturing nexus. The Chrysler 300, “Imported from Detroit,” is made in Brampton, a few hours up the 401. When Detroit’s auto sector takes a hit, so, too, does Windsor (and the rest of Ontario). Exchange rates affect the economic viability of automotive trade through steel, machine tools, and parts.

For the most part, this connection works– for tourism (in addition to Caesar’s Windsor Casino and the city itself, Essex County boasts a wealth of natural areas, wineries, and charming small towns), for healthcare (Canadian nurses working in Detroit hospitals), and for workforce (Canadian automotive engineers employed in Metro Detroit). If you draw boundaries around a hypothetical international Detroit Metro area in Ontario– that roughly mirror the boundaries of the Combined Statistical Area that includes Flint, Ann Arbor, and (US) Metro Detroit- our Canadian brethren account for about 13% of our greater metro area (this includes Sarnia and Lambton County, Chatham-Kent, Essex County, and the city of Windsor, but it’s a similar percentage if you compare Windsor-Essex to the 3.7 million people of metro Detroit).

But in the insular imagination of many Southeast Michiganders, Windsor is that place that Detroiters go when they’re 19 to get drunk and then forget about. Evening descends on downtown Windsor’s Ouelette Avenue, bringing a nefarious condition that a Canadian friend once called “hoochie night time,” and the strip is populated with young Michiganders eager to enjoy a Long Island Iced Tea for $3– and at those favo(u)rable exchange rates, too!

This betrays an unfortunately limited cultural connectivity in the present day between the two cities, which share centuries of history.

I’ve long been a hype man for the city and its weird, gritty charm and diversity, having been jokingly called Flavor Flav to Windsor Mayor Drew Dilkens‘ Chuck D (though I have admittedly never met or interacted with the man). So, as a regular international man of mystery who is also carless as of December (shoutout here to Progressive Insurance for paying out all of zero dollars and to the red light runner who totaled my yellow Toyota and then drove off into the night), I sometimes have to get creative about how to get around in a border town.

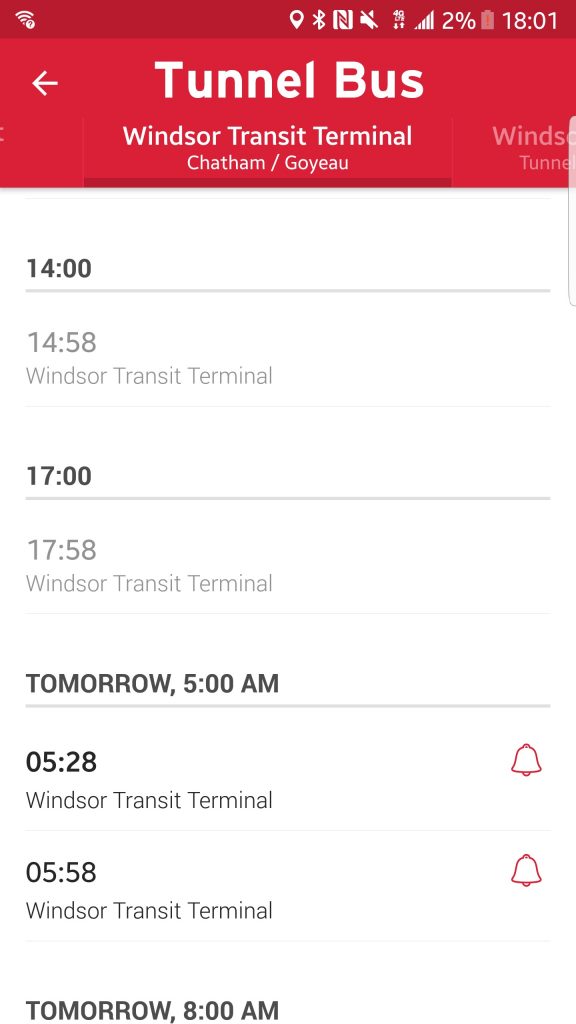

Taxis are exorbitant (there’s a $20 CAD surcharge on any trip across the bridge, and kilometers rack up on the meter way faster than miles). There is no bike connectivity between the two cities, except on the tunnel bus, which can carry up to two bikes on a front rack. One man– the hero we need, though perhaps not the hero we deserve- once did try riding his bike through the tunnel to get to a Steely Dan concert, of all places. (It didn’t end well.) And buses haven’t historically been terribly reliable in Detroit: Between limited frequency and limited reliability, one basically has to plan on 45 minutes to an hour and a half to get anywhere.

To get to Windsor, a car trip, door to door, takes five to fifteen minutes with favorable conditions at the customs plazas. Rush hour takes longer, and delays can make that trip take up to an hour. I can’t get a Nexus card for expedited entry because CBP has apparently deemed me a threat to national security (I’m not kidding).

HISTORICAL CONNECTIVITY VS. MODERN INTERNATIONAL BUREAUCRACY

The two cities used to be more interconnected, and you don’t have to go back to the ferry era, nor the era when rum runners drove across the frozen Detroit River (they usually made it). Farecards used to be able to be used for transfers between Transit Windsor buses and DDOT, thought at the time to be the first international farecard compatibility among municipal transit systems in the world, according to Transit Windsor Executive Director Pat Delmore.

But that stopped during Detroit’s 2013 bankruptcy. Lawyers got involved, as they do, and decided that because the structure of Detroit’s insurance had changed, Transit Windsor could theoretically be held liable in the event of an incident on a bus in Detroit involving a ticket purchased in Windsor, and the connectivity ceased. How can one get around without a car?

“Just drive,” the prevailing logic suggests, of course– since every man, woman, and child in Southeast Michigan and Southeastern Ontario is expected to lease a new, Ford F250 Super Duty.

Windsor’s Wyandotte Street makes for a convenient bus connection for my standing Monday night appointment in Walkerville.

But now, for several hours each night, while the tunnel is under construction, there is no public transit connecting Detroit, Michigan, and Windsor, Ontario. Let’s rewind for a minute: For several hours each night, there is no public transit connection between one of the most important international border crossings in the world. And, the roughly twelve thousand cars that pass through the tunnel every day, buses only come hourly, and the cars make up about 98% of the tunnel traffic, according to the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel Authority. Most of those cars have a single driver, too.

Here’s why that’s problematic:

Windsor and Detroit comprise one of the most important international border crossings in the world, connecting the most important player in the global economy with its most important trade partner, which, for most intents and purposes, functions more like a giant, 51st state, than it does like a foreign country. If Detroit’s economy collapses, Windsor collapses. If Windsor’s economy collapses, Detroit takes a huge hit.

Focusing in on the physical configuration of the border, almost half of the truck traffic between the US and Canada passes across one bridge, and one bridge alone. (Trucks can’t go through the tunnel.) Limited transit and choke points for car and truck traffic make congestion a huge problem. $100 billion in trade crosses the bridge per year, which generates about a billion dollar per year of revenue to the Moroun empire– to say nothing of the impact of the thousands of Canadian workers who cross into the United States every day through the bridge and the tunnel (likely also in the billions).

The Ambassador Bridge, which Forbes’ Joan Muller has called an “economic umbilical cord” between the two countries, is a privately owned monopoly, the only private border crossing in the world. It’s also falling apart. These two conditions have been the subject of increasing scrutiny by international governments as well as the companies that rely on the bridge to transport what amounts to about a quarter of all trade between Canada and the US.

A substantial chunk of the bridge’s traffic is expected to be diverted to the Gordie Howe bridge when it is completed some time in the distant future. The notorious owner, transportation mogul Matty Moroun, facing the threat of losing one of the most profitable monopolies in American history, has fought tooth and nail against the new bridge, ranging from allegedly waging disinformation campaigns in Delray to rally residents against the new bridge, to suing based on every conceivable or inconceivable legal remedy.

(TheHUB has provided coverage of the bridge, both from an economic perspective and from a ground level neighborhood perspective within Delray, and the Free Press did a bleak, poignant, and frank portrait of the neighborhood in December, illustrating the ubitquity of blight and health problems from poor air quality.)

Truck traffic won’t be affected by transit, but the diversion of car traffic from the tunnel to the bridge means not only delays, but also additional strain on infrastructure. The tunnel is already undergoing a multimillion dollar renovation, and doesn’t have the political leverage power to readily influence public transit expansion on its own.

“When you get right down to it, we’re really just a piece of road,” Detroit-Windsor Tunnel CEO Neil Belitsky told us.

Transit Windsor’s Pat Delmore says that Transit Windsor has worked closely with US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) throughout the process of the tunnel closure and says that, unfortunately, there wasn’t the ability– or even the will, perhaps- to accommodate bus traffic across the bridge during the closure.

This is in part a matter of how the space is awkwardly set up. Since the bridge monopoly owns a consequential portion of the 62 acres comprising the plaza, roadways, and other surfaces, CBP is, at least to some degree, at their mercy (see “Why Monopolies Are Bad, For Dummies”). The ire that has gradually developed over the years, carried by a coterie of international entities frustrated with Mr. Moroun’s antics, has largely given way to a disenchanted kind of resignation, and most simply hope that his son is more magnanimous in dealing with the border issue.

For scenarios in which the CBP has to assume additional responsibility for, say, processing busloads of passengers, it can engage in what is called a “reimbursable services agreement.” This would involve juggling a portion of its 1400 statewide staff of agents, inspectors, and administrative support. But, according to a CBP spokesperson, that hasn’t come up with Transit Windsor.

“We’re always open to ideas of providing services,” spokesman Ken Hammond said, “and any of our facility operators who want to talk expansion… there’s never an issue where we won’t listen.”

Pat Delmore doesn’t entirely agree with that assessment. He said the CBP ultimately was unable to provide a solution to process potentially busloads of passengers at its facility, which is substantially smaller than the tunnel processing facility, so the service was simply cancelled during that window. Pitting a local Canadian transit agency against a US federal agency against a monopolistic business enterprise whose sole interest is to make as much money as possible at the expense of both parties involved, one could look at the Condorcet Paradox, a classical problem that illustrates how, although three separate parties may prefer one option to another, they are unlikely to achieve an optimal outcome in scenarios where one choice must prevail.

So, forget tourism, forget the international workforce: You can’t get there from here. (The Ambassador Bridge company, unsurprisingly, did not return multiple requests for comment, and the Windsor-Detroit Bridge Authority, a Crown corporation tasked with building the new Gordie Howe bridge, declined to comment.)

Certainly, forget equity, a topic that has come up frequently in the transportation dialogue: If you don’t have a car, well, tough. This is a border for cars and cars only! A pedestrian and bike ferry has been proposed, but this is only at the drawing board phase at this point, and seems mostly limited to the bike communities on both sides of the river.

Asked whether he would be in favor of the RTA proposal to expand transit in Southeast Michigan, Delmore said: “Any time that you have an ability to connect more people with transit, you’re doing a good thing, whether you want to look at convenience, the social aspect in providing social opportunities for people being independent, or for the environment.”

He says that the RTA expansion, especially if it improved connectivity with cross-border transportation options, could be a boon for both sides of the region. Still, he acknowledges that this is as much as cultural problem as a political one, citing the University of Windsor’s UPass, a bus pass given to students, as an example of how to affordably provide transportation access while also facilitating awareness about transit– even if not every student uses it. “Half the students may never even pick up their pass, but it’s no different from them paying for a sporting facility that they’ll never use,” he says, and adds that, for the students who do use it, it is an invaluable asset to get around town. This issue has come up recently in CBC coverage with nearby St. Clair College, where a large influx of carless international students coming for summer classes have struggled with accessibility of transit.

As far as the RTA, Delmore thinks it is possible, so long as the narrative is packaged and sold effectively. And, given that transit is a hot-button topic in Michigan, that’s a big if, but, “once they get it, they love it,” he says. Transit Windsor has been actively considering expanding its Detroit-side connectivity, and just recently dispatched its first Tunnel buses bound for the Little Caesars Arena, although a direct relationship with the RTA is fairly limited.

Neil Belitsky, of the tunnel authority, hopes that the tunnel will continue to facilitate public transit connectivity.

“We’ve hosted Transit Windsor for many years and plan on hosting them in the future,” he said. Asked whether increased bus service wouldn’t hurt their bottom line, he said that buses pay a different rate from cars anyway, but a decrease in car traffic might mean less wear on the infrastructure in the aging tunnel itself.

One other certainty is that a spike in gas prices would be a huge incentive to create better transit infrastructure, especially urban-to-suburban infrastructure in this case, and would have a huge impact on demand. While still below their 2011-2014 high marks, oil prices are up more than fifty percent in the past year, which makes commuting ever more spendy (as an aside, Ford ironically seemed to think this was a great time to get out of the small car market to sell gas-guzzling trucks).

The US Department of Transportation has noted that transit ridership increases in correlation to gas prices fairly quickly, and Ontario has seen modest increases since Hurricane Harvey last fall (gas in Ontario is more expensive than US gas, between $3-4 USD per gallon). It’s unclear whether the distance commuters from Windsor to Detroit would be quite as affected by that, particularly those automotive workers in higher income brackets who clog the tunnel every day for rush hour in single-occupant vehicles toward suburban jobs. Economists call this a question of “elasticity”– that is, if the price of gas trends upward, how much and how quickly does it stretch demand for transit? How far would it have to go up to change commuter behavior?

This is yet somewhat of a wildcard, and the uncertain prospect of increasing gas prices are by no means a safe bet for the RTA moving forward. It’s also unclear what will happen with the RTA, but, as far as buses home after trivia night at the Vic, it looks like I will just have to wait until the tunnel completion to resume evening bus trips.

Asked what he thought about the RTA proposal and whether he thought the car culture of the region wasn’t at odds with the idea of an expanded regional transit program, Belitsky remained stoic, but suggested that anything’s possible. “Listen,” he said, “I grew up in New York City. I didn’t know how to drive a car until after college.”