Ann Arbor Axes Parking Minimums. In Michigan, That’s Huge.

The city of Ann Arbor officially abolished parking minimums yesterday with the passage of an amendment to the city’s development code. It’s a huge move in a growing city that is sort of the progressive anchor of a region that has historically been pretty reactionary– at least in the urban planning and development policy space. The vote, on what was called “An Ordinance to Amend Sections 5.16.1.A, 5.16.2.A, 5.16.2.B, 5.16.3.J, 5.16.3.P, 5.16.4.B, 5.16.6.C, 5.16.6.G, and to repeal and replace Section 5.19 of Chapter 55 (Unified Development Code) of Title V of Code of the City of Ann Arbor – (Amend Parking Standards) (ORD-22-13),” passed with broad support, save one dissenting voice from Councilmember Jeff Hayner, who, well. Suffice it to say, this may bode well for a region that has struggled to adopt more progressive transportation and land use policy measures.

Why are parking minimums bad? Actually, hold up. What are parking minimums?

“Parking minimums” refer to the requirements in most zoning codes that say that when you build a building, you have to create such-and-such minimum amount of off-street parking. While the ostensible idea is to make sure everyone has a place to park, the reality is that it drives up costs for new construction, which drives up rents. It also makes it harder to build things. In a densely packed urban environment, land is expensive. It is even more expensive if you have to acquire additional land– or even tear down a nearby, serviceable building- just for surface parking.

Quick facts:

- Parking is one of the largest single land uses in the United States.

- Cars sit unused and off for most of their lives.

- A parking space ranges in cost from as little as a few thousand dollars for paving over grass with asphalt, to $30,000 or more for a space in an underground structure.

- Requiring small business owners to provide parking amounts to a subsidy for cars, and can be extremely expensive.

- Parking minimums drive up the cost of new construction, which challenges housing affordability.

To the uninitiated, a “standard” parking space occupies a gross area of 162 square feet. But when you factor in the additional area for pulling in and out, turning, etc., it’s more like double that at 320 square feet– or more. Parking garages are notoriously inefficient, with a third or less of their space dedicated to actual parking spaces, while it’s possible to get close to 100% efficiency with certain designs of parking arrangements. (That is a story for another day). But suffice it to say, the surfeit of free and cheap parking is one of those things that we never really think about in common conversation about cities. Usually it’s just, “oh, man, it’s so hard to find a parking spot!”

Let The Market Regulate Parking!

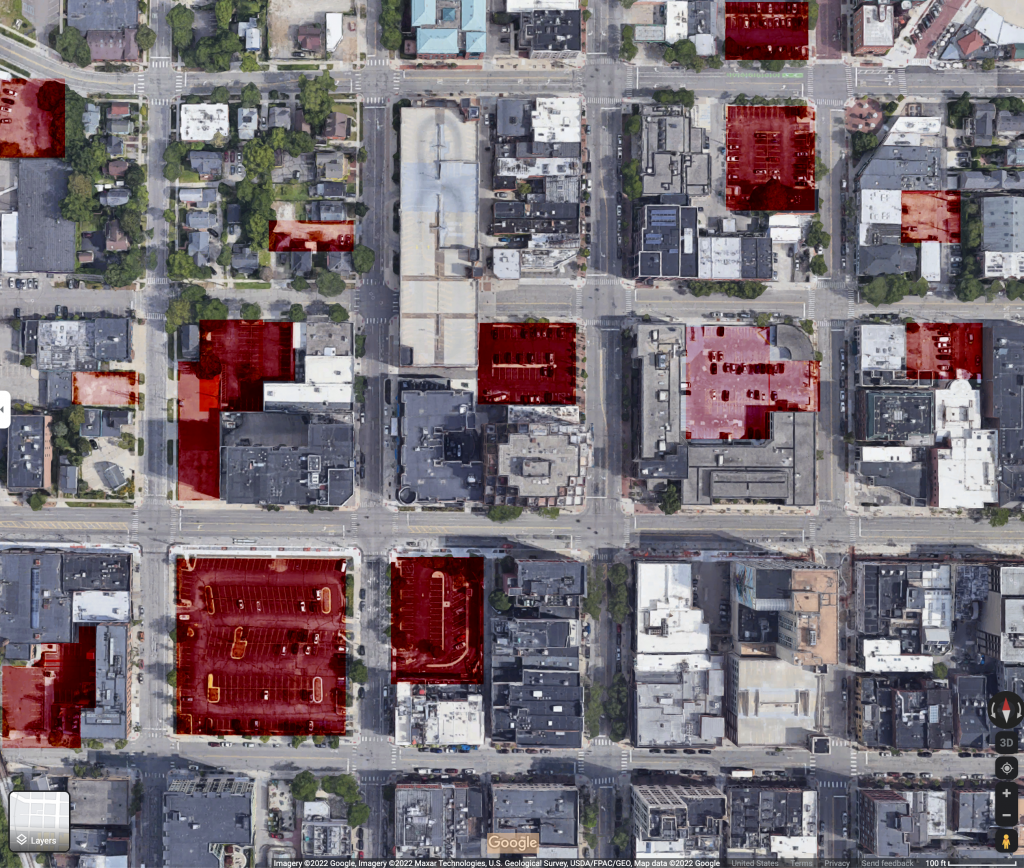

As I Illustrated many moons ago in the Detroit Park City project, parking occupies a truly unfathomable amount of land in the United States and Canada. It costs a lot of money. It is also land that could be put to other uses– whether agriculture or buildings. Parking lots don’t really generate tax revenue, and few cities (none that I am aware of) assess value capture fees of any sort on parking. It is environmentally, well, bad, to say the least. Parking lots inflict a heavy toll on ambient air temperatures because of their high thermal mass and (usually) low albedo. Black asphalt, which is literally oil mixed with rocks and smooshed into a smooth form, emits that characteristic, dank, hydrocarbon smell– that isn’t good for you. Concrete, in comparison, is far more expensive. It is also quite carbon-intensive to produce. So, you’ve got a carbon-intensive product that has to be applied to a huge area, that then holds a lot of heat.

The response– in academic study and professional practice- is to suggest that parking should be regulated as a market good. If I could distill one talking point from The High Cost of Free Parking, it would be this: if there is no parking available somewhere during a given time frame, the parking is too cheap. Can’t find a space anywhere and it’s only 50 cents an hour? Maybe it should be a dollar an hour! Match price to suit demand! There are also ways to ensure that people with limited physical mobility can still get to where they’re going, because there are a specified number of accessible spaces and pickup/dropoff areas.

Simple Illustration: Losing $60,000 A Year Vs. Making $250,000 A Year

But “where will we park?” (see Downton Abbey reference below) is a dominant discussion for especially suburbanites who frankly might not know any better. The political pressure for cities to provide free parking, either in municipal lots or on public streets, amounts to a massive subsidy that costs taxpayers dearly. Imagine that a municipal lot requires a few hundred dollars per year per space in terms of maintenance and amortized construction costs. Now, imagine that this municipal lot has 200 spaces. If a parking space works out to 320 square feet of paved area, that means that you could fit a two-bedroom apartment on the space created by 3 parking spaces. A five-story building on the site of this hypothetical municipal lot could create 250 or more of these two-bedroom apartment units. Now, instead of the municipality spending $60,000 on capital costs per year, they’re now making several times that in property tax revenue. This is to say nothing of the sales tax revenue that several hundred new residents will bring into the municipality.

It’s particularly valuable to consider in cities like Detroit, which boast as much as half of a downtown area covered in surface parking lots. Ann Arbor, for its part, has far less parking in the downtown. But it does have a number of structures, that are all relatively cheap. And it’s often possible to find a street space, depending on where you go. There are still surface lots. But new development being able to avoid parking minimums is going to be a lifesaver for the city’s affordable housing crunch, which has been nuts even prior to the current bubble, owing to massive market manipulation by the University, foreign speculators looking for a stable market, and a spatially constrained downtown area.

New Development Illustration

It gets dicier still when you imagine how much it might cost for a developer to build additional off-street parking spaces. Let’s say you acquire a house for $250,000 and plan to spend $1 million to demolish it and turn it into a three-story building with six condo units. You might be required to provide 9-12 off-street parking spaces for this. This might mean you’ll have to buy the house next door, say, for another $250,000, demolish that, and pave over the lot. It’s simple math, but it’s easy to understand why parking minimums don’t make sense.

Onward for Michigan? Maybe?

Michigan planning nerds– all seven of us- are enjoying a rare moment in the sun this month with the passage of the parking reform measure and the approval of the universal SMART millage in Oakland County for the fall ballot. We can learn from Ann Arbor’s moves. We just need to figure out a way to make sure we are providing ample alternatives as we are reforming these systems. We should always consider accessibility to those with limited mobility when addressing parking reform. We should also make sure there is adequate support– whether something as basic as signage or something as macro level as system funding- for transit and alternatives. But in the meantime, Ann Arbor is giving us life! Check out the map below from the Parking Reform Network on cities that have successfully eliminated parking minimums.

For further reading, check out the Parking Reform Network. Or, read some of the works of St. Donald of Shoup, patron saint of parking reform. Or check out Detroit Park City, a design study I did of a bunch of vacant sites around Detroit, reimagining how they could be converted from simple parking lots into productive buildings.