Is It Time For A New Standard For Measuring EV Fuel Efficiency?

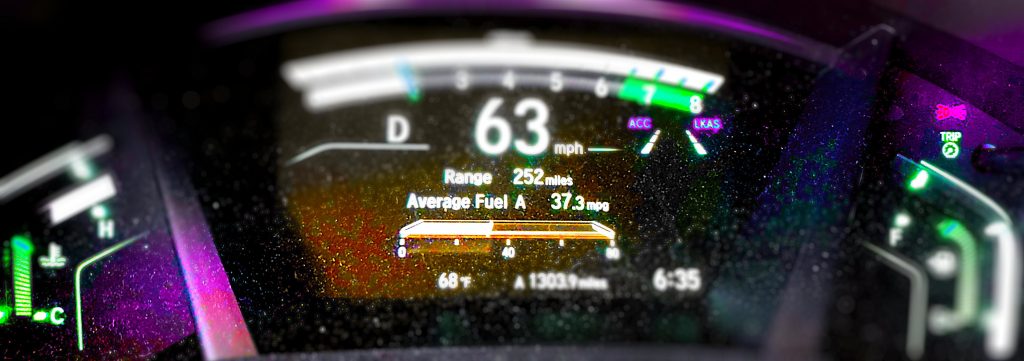

While I was glad to ditch my personal car in August, our household has a new-used car, which we were able to take on a recent road trip. It’s a 2018 Honda CRV. The fuel economy, according to the EPA standard, is rated at 28 in the city and 34 on the highway. The lifetime fuel efficiency is in the low 30s, probably as a product of aggressive city driving by its former owner. But we’ve been able to pull as much as 40mpg across a combination of city and highway driving. Exceeding by small margins is one thing. But 10% seems like a lot! Is it time to revisit the EPA fuel economy standards and think about a new one?

Problems of the EPA Standard

There are plenty of complicating factors to be considered in the widely observed variances in fuel economy. An Edmunds article noted:

At the top of the list is how much city driving the car does. The proportion of stop-and-go driving could reduce the EPA combined city/highway fuel efficiency for a particular vehicle by as much as 27 percent, they say. Individual driving style can cause the second biggest variation, lowering fuel efficiency by up to 18 percent. Edmunds testing supports these conclusions. “Calm” drivers, those motorists who don’t accelerate constantly and who avoid unnecessary lane changes, get 35 percent better fuel economy than other drivers.

Other factors in play are air-conditioner use (up to 14 percent reduction in fuel efficiency), vehicle size (up to 15 percent reduction) and the region in which the vehicle is primarily operated (up to 12 percent less fuel efficiency, because hot weather and mountainous conditions take a toll on fuel economy).

Fuel type also affects mileage. Most gasoline in the U.S. today is 8-10 percent ethanol, but the EPA does its tests with 100 percent gasoline in the tank. The use of ethanol to increase the amount of oxygen in gasoline for better combustion can reduce fuel efficiency by around 2 percent all by itself.

The Complication of Measuring Plug-in Electrics

Plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) that can operate in all-electric mode qualify as electric vehicles under the federal tax credit, even if their EV ranges are relatively short. The Toyota RAV4 Prime is perhaps the best example of a car that is entirely serviceable within Big Car’s new paradigm of SUVs. The fuel economy of plug-in hybrids are, though, somewhat bizarrely, classified based on their combined fuel economy. So, the RAV4 Prime comes in at “94mpg.” It seems like there are a few different measurements:

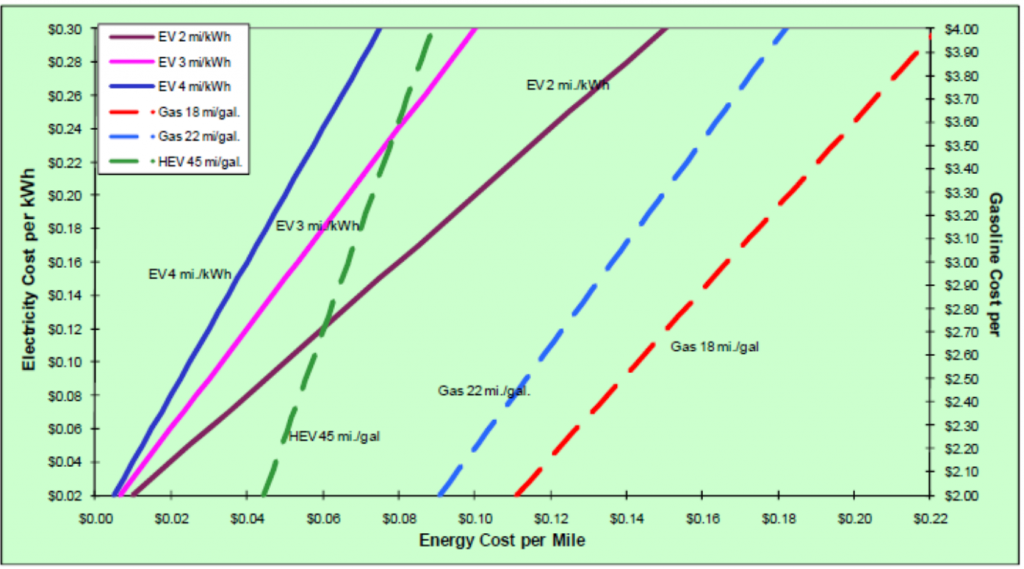

- MPG and MPGe. MPG is, of course, the standard in the United States. We used to care about it before Big SUV came in and ruined everything in the age of cheap gas– but we’ve also marginally improved the fuel efficiency of giant vehicles from, say, the teens to the mid 20’s. The rest of the world refers to “liters per 100km,” or, “L/100km.” MPGe was developed to compare electric vehicles to ICE ones on an apples-to-apples metric. It’s perhaps the best metric we can use to illustrate

- KWh per mile. This is a new measurement I’ve seen for electric cars. It’s valuable in thinking about what extra weight does to drag an electric car, especially with luxury features and a powerful engine. Critics have observed this about the new electric Hummer. It’s got the worst of both worlds, they note— all of the ungainly weight of a hummer plus a relatively novel power source that is strained to move the damn thing. This measurement at least partially addressed the disparity in engine efficiency that explains why ICE cars perform so much better on the highway.

What about a measurement like joules per mile?

Critics might argue that it makes it harder to convert easily to things like gas prices. But this can easily be accounted for through some sort of infographic or label. Imagine that car labels included something like the yellow energy labels on appliances sold in the United States– showing that this appliance uses more or less energy than its peers, and is expected to cost you “x” compared to “y” average for this type of product. It’d be possible to use a moving average of gas prices, which fluctuate substantially, as do energy prices used to calculate the Energy Star labels and what have you. Of course, there are other costs associated with getting set up with an EV in the first place.

But in the long run, it’d probably be more useful to customers to be able to compare apples to apples as far as the actual efficiency of converting a fuel source into movement. Kilojoules per mile? I mean, kilometer, preferably. But it seems like it might be valuable to reconsider the EPA fuel standard, especially when we’re thinking about EV fuel efficiency.