No, Electric Scooters Aren’t More Dangerous Than Other Modes of Transportation.

Most of us folk who are terminally mired in The Discourse have seen that meme– the one that shows a car crash, a car parked on a sidewalk, or something else car-related that undermines urban mobility or public safety- with the caption, “fricking scooters!” The point of the meme is to illustrate the fact that scooters are blamed for all urban mobility problems, in spite of the fact that most city and planning problems are, in fact, caused by cars. Or an over-reliance on them. This, plus the proliferation of unregulated and dangerous lithium-ion batteries that are prone to blow up or catch fire, has pushed a lot of cities to ban both ebikes and escooters. But now we have some more evidence to disprove that either of these are more dangerous than alternatives, thanks to a new report from Rutgers University on the subject.

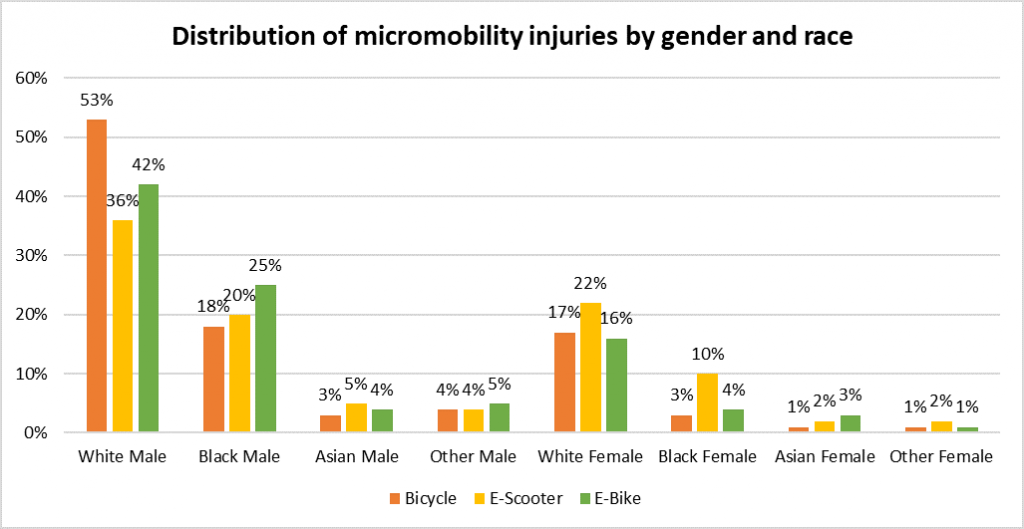

The report, by Hannah Younes, Robert Noland, and Leigh Ann Von Hagen, compares demographic categories to understand the relative vulnerability of different micromobility users. If you took away the title and legend of the following chart (“distribution of micromobility injuries by gender and race”), you might have a hard time trying to figure out what on earth would be the possible area in which white males are substantially more likely to be injured than anyone else other than, I don’t know, whatever it is that white people love doing:

Interestingly but perhaps not at all shockingly, the researchers found far higher rates of injuries among cyclists (riders of acoustic bikes, as it were) than among e-mobility users:

The vast majority of injured micromobility users who end up in an emergency department are treated and released without being admitted in the hospital. Those with e-scooter injuries are more likely to be treated and released (85%) than those with e-bike (81%) or bicycle injuries (79%), although not by a large margin. Fire-related injuries from a lithium battery explosion were present in one of the e-bike injuries (0.2%) and two of the e-scooter injuries (0.2%). Very few micromobility-related injured patients suffer fatal injuries, although based on the 2021 and 2022 datasets, a slightly higher proportion of cyclists suffered fatal injuries compared to e-bike and e-scooter users.

– Younes, Noland, and Von Hagen (2023)

This is perhaps complicated by the fact that scooters, bikes, and eBikes effectively all share the same poorly developed infrastructure in a society built around cars. In some future, there are bike lanes that allow for fast travel and slow travel, and fewer lanes for rapidly depreciating assets that are only used for less than 5% of their productive lifespans.

It does raise some interesting questions about the rate of use among certain demographic groups, though, or among people in certain areas. I read one report that said, for example, that bicycle use as a primary mode of transportation closely mirrors socioeconomics rather than favoring white people as a user demographic, as is the stereotype. I am filled with varieties of rage thinking about that paper, “Bike lanes are white lanes,” which, while partially on-point in its critiques, I feel kind of missed the point. But I digress– the point here is that everyone deserves safe streets and safe mobility options, and we should work to create parity in funding and access, if not actually prioritizing these non-car modes of transportation (monocle-dropping moment, I know)!

I keep thinking back to what then-Lime Director of Government Relations (now *m*z*n) Nico Probst said on a panel at a conference many years ago: that using these devices turns you into an advocate for better infrastructure, because, well, it has to. When you ride over potholes in a scooter– namely, bumps and cracks you might not even notice while in a motorcar- you start thinking, “man, how is it possible that our infrastructure is this bad?” People who are experientially radicalized as agents of the War on Cars, you know.

Similarly, anyone who has ever experienced the terror of a bicycle accident or car crash (or even a could-have-been-worse near-miss, which I have at least once a year) can attest to the fact that no one should ever have to go through that. And we make a choice as a society, when we prioritize road engineering for high speeds and high throughput over safety of human beings, that hundreds of thousands of people will go through that each year.

Toward Better Data And Better Policy

Crash data are incomplete. This is a jurisdictional problem as well as a mode problem. We have a patchwork of thousands of police departments and road engineering departments that, by and large, don’t care about micromobility users or pedestrians, and only care about cars and drivers. The mode problem is that our entire society is built around the automobile.

But still, we find data from the Consumer Product Safety Commission that suggests– with a particularly alarmist title about the “soaring” fatalities from eBikes and eScooters- that an average of 46 Americans have died each year from using micromobility devices. Consider: that is less than a tenth of one percent of the number of Americans who die each year in cars. Furthermore, we can only imagine how many of those 46 people who die each year have died as a result of cars. Just another example of why we need to prioritize, in the words of the Rutgers researchers, “(1) proper e-micromobility infrastructure, including separated paths and charging facilities, (2) measures to calm motor vehicle traffic, such as reducing speed limits, narrowing lanes, and raising intersections, [and] (3) ensuring good post-crash care in the case of an injury.” It is time! But now, we have more of the data to prove how and why.