Why Regulating Methane, Not CO2, Is Key to Climate Policy

The current craze over electrification is focused on slowing the emissions of carbon dioxide to mitigate the most catastrophic effects of climate change. While there are many problems with the most popular solutions to the carbon crisis– notably the idea that we can just build a lot of electrical cars and still consume obscene amounts of resources with no regard for the complete lack of sustainability of doing so– one elephant in the room is the topic of methane emissions, which is going to be a problem whether or not we’re electrifying things. Why? Methane factors into not only heating fuel usage (and fuel for domestic hot water), but also into power generation from fossil (“natural”) gas. It’s also something that is frequently leaked into the atmosphere at prodigious rates. This is a subject that news media have at least paid a bit of attention to, although it’s far removed from flashy climate solutions or political talking points (except inasmuch as it pisses off the oil and gas lobby), so it’s avoided becoming commonplace dinner table conversation.

How Bad Is Methane, really?

To the uninitiated, not all greenhouse gases are created equal. Carbon dioxide is actually the least bad of the major greenhouse gases– there’s just way more of it than there are of the other ones. This chart from the EPA shows, for example, that sulfur hexafluoride– something that is used, esoterically but significantly, in industrial transformers- is 23,500 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than CO2. Methane? A measly 28 times more potent than CO2. Those are rookie numbers, methane! That chart is why there are regulations on things like commercial refrigerants, which are usually heavy hydrocarbons that really, really should not be released into the atmosphere, no matter how badly you want that scrap copper from that fridge you found in the alley.

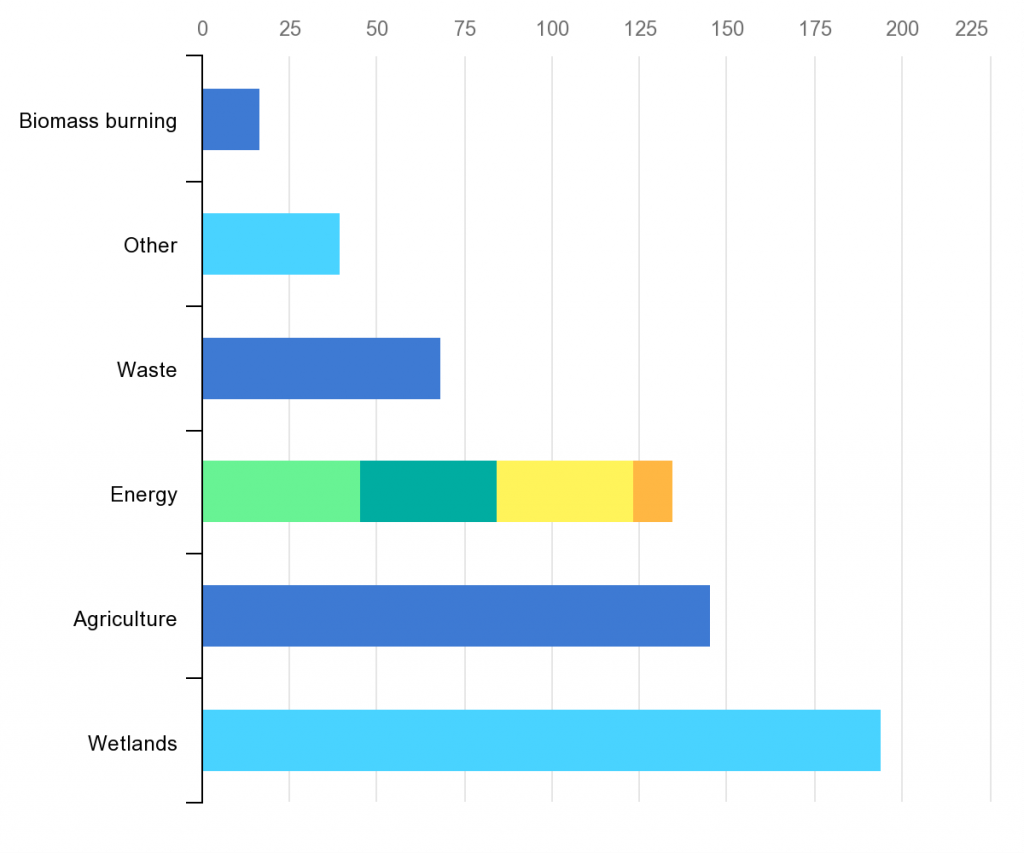

The below table shows some low-end estimates of global methane emissions per year, and shows us that they’re equivalent to about two billion passenger cars on the roads. If you said, “hey, I didn’t even realize there were two billion passenger cars on the roads!” then you’d be correct, as there are well under 2 billion passenger cars on the roads (and hopefully we can decrease that number in coming years, too– or at least, you know, halve our VMT).

This illustrates fairly significantly why we should:

- Phase out fossil gas in new construction. Any building built to modern building code will not require fossil gas for heating. This is true in northern climates in civilized jurisdictions, and it’s therefore ever more true in southern climates with lower heating demand (and a desperate need to lower cooling demand).

- Regulate methane at the point of extraction. Companies can easily prevent methane from escaping from wells.

- Incentivize gas capture from industrial applications. This isn’t as directly related, but it’s something I spend plenty of time thinking about every time I see the gas flares from my local steel mill, oil refinery, or what have you. Gas flares are a good nexus of particulate emissions, combustible gas emissions, and carbon dioxide (resulting from the combustion of those gases). Let’s stop doing that. The air smells bad.

But anyway, about that chart:

| Year | Methane emissions (million metric tons) | GWP equivalent (million metric tons of CO2) | Equivalent number of passenger cars [driven for one year] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 362 | 9,050 | 1.97 billion |

| 2011 | 367 | 9,245 | 2.01 billion |

| 2012 | 371 | 9,340 | 2.03 billion |

| 2013 | 375 | 9,435 | 2.05 billion |

| 2014 | 379 | 9,530 | 2.07 billion |

| 2015 | 383 | 9,625 | 2.09 billion |

| 2016 | 387 | 9,720 | 2.11 billion |

| 2017 | 391 | 9,815 | 2.13 billion |

| 2018 | 395 | 9,910 | 2.15 billion |

| 2019 | 399 | 10,005 | 2.17 billion |

Is That All Anthropogenic Sources of Methane?

I’m glad you asked! According to the EPA, in the United States, the largest sources of anthropogenic methane emissions are:

- Energy (33%): natural gas and petroleum systems, including oil and gas drilling, production, processing, storage, and transportation

- Agriculture (29%): enteric fermentation in livestock, manure management, and rice cultivation

- Waste management (18%): landfills and wastewater treatment; and

- Other (20%): including coal mining, mobile sources, and other industrial processes.

So, we’ve got lots of options here for where we can start. Landfills are a huge one, and virtually all of that comes from food waste. Clean plate club, people! (But seriously– there is no reason why every major city in the United States doesn’t have municipal compost pickup). “Enteric fermentation” in livestock? That means cow farts, people. Maybe skip that 8 oz. burger that is four times the size that your body can actually reasonably metabolize the nutrients from in a single meal. For energy? That number comprises waste emissions from drilling and extraction as well as waste leaking out of municipal gas distribution systems. Stop wasting stuff, people, it’s bad.

Okay, But What About Wetlands?

It’s true that wetland emit a lot of methane– as many as 200 million metric tons per year, according to estimates from the IAEA. But wetlands also sequester carbon and provide other benefits, ranging from creating biodiversity to absorbing excess rainwater (avoiding it being channeled into, say, cities, viz. your basement). the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that wetlands globally also sequester something to the tune of 1.5 gigatons of carbon per year, or about 6-9% of global fossil fuel emissions.

The hydrological and everything else-ological benefits of wetlands seem a good enough reason to keep them, but the carbon sequestration is especially important. It is also a possibility for how we might consider restoring what were once expansive wetlands covering much of the middle states– before industrial agriculture whose product has mostly been directed to the manufacture of animal feed or ethanol. While that’s a story for another day, it’s worth mentioning as wetland restoration and, in general, rewilding of green space, is a solution that is comparatively lower tech than, say, carbon capture solutions that don’t work, or electric cars that won’t decarbonize the economy. It’s also notable given that the conversion of so much wetland to agriculture substantially increases the anthropogenic inventory of methane gas emissions.

So, About That Methane Tax?

As Congressional Democrats seem hellbent on avoiding much in the way of real progressive governance and Republicans are more interested in inspecting your children’s genitals, it’s anyone’s guess as to whether we’re going to see much in the way of action on either CO2 or CH4. For me, though? The “billions of cars” really did it for me. Shocking, and a reminder that we need to keep pushing on new ways to address this. Regulating methane is that much easier at the point of emissions because it’s waste– it’s not being burned. We can all agree that waste reduction is good.