Oakland County Approves Universal SMART Millage For Fall Ballot

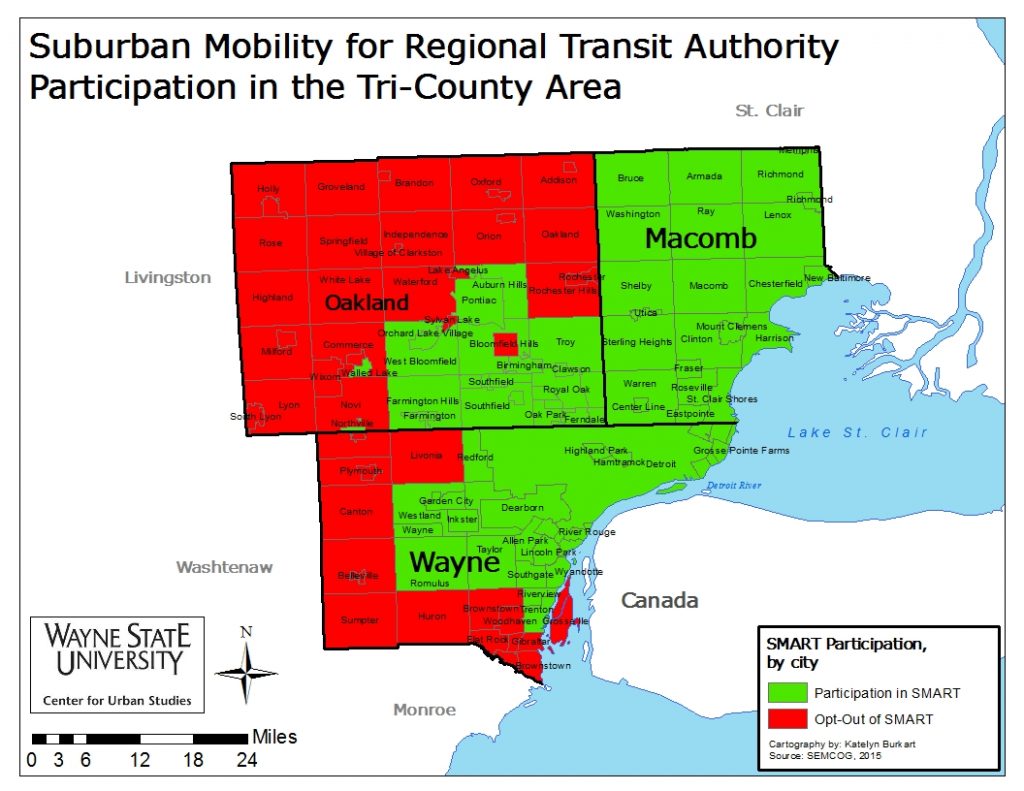

It’s official: Oakland County will have an opportunity to vote on transit investment in the fall! Such was the determination last night of a meeting of the county board of commissioners, who voted 13-7 to approve the ballot measure. Metro Detroit mobility advocates will rejoice, because this means two very specific things. First, if the measure passes, it’s going to eliminate Oakland County’s current patchwork setup of transit accessibility. This means that the suburban transit authority could make transit accessible across the entire region without the hellish patchwork created by the “opt-out” framework. Second, it’s also going to potentially pave the way for major regional improvements in coming years.

Yes, yes, yes– I know, we’ve talked about this nonstop for years. And when your system is in as bad shape as ours is in Michigan, one must celebrate the smallest of wins! This one happens to be a potentially huge step that avoids the pitfall of the Regional Transit Authority’s “lather, rinse, repeat” approach of, well, losing ballot initiatives for woefully unspecific proposals for regional transit expansion.

The story of the “Walking Man”, a Detroit resident who walked 21 miles a day to his job in the transit opt-out suburb of Rochester Hills demonstrates the inequity, indignity, and absurdity of this patchwork system.

Stitching Together The Patchwork

To the uninitiated, southeast Michigan is the land that time forgot, at least as far as regional policy thinking is concerned. Such has been noted extensively in academic analysis of the city vs. suburb divide for more than half a century. But you don’t need to be Thomas Sugrue to understand this, especially if you’ve ever taken a bus from Detroit to virtually any suburb. With the exception of a few routes that run on the major roads radiating out of Downtown Detroit (really just the Airport route and the Woodward route), all other buses quite literally stop at the city limits, requiring riders crossing Detroit city limits to switch between buses run by the Detroit Department of Transportation and those of SMART, the suburban transit agency. Many Oakland County communities opt out of the SMART system entirely, choosing to run limited paratransit systems for residents only or in some cases, nothing at all.

It is not hard to imagine how this becomes a logistical clusterfuck for a working person trying to get to, well, work. The story of the “Walking Man“, a Detroit resident who walked 21 miles a day to his job in the transit opt-out suburb of Rochester Hills demonstrates the inequity, indignity, and absurdity of this patchwork system.

The problem is widely recognized. But transit is a third rail in the politics of suburban Detroit. After yet another attempt at building a regional transit system failed in the 1990s due to racial tension between city and suburbs, Oakland County allowed its cities and townships to exit the SMART bus system and stop paying the funding millage, despite containing major suburban job hubs. Those communities were now out of the reach of the tens of thousands of area residents, disproportionately Black and poor, who did not have access to a car. The most recent attempt to restore countywide transit in 2009 failed along partisan lines in the County Commission due to the influence of County Executive and segregationist L. Brooks Patterson.

However, a suburban political realignment, new leadership in Oakland County, and the continued effort of transit advocates mean that change could happen at last. Democrats captured the majority at the Oakland County Commission in 2018. Brooks Patterson passed away in 2019, succeeded by an openly pro-transit advocate from the heavily urban part of the county bordering Detroit.

At a County Commission meeting on August 4, 2022, County Commission Chair David Woodward, backed by a transit-supportive majority, introduced legislation for a new countywide transit tax measure — no opt-outs! The entire county would pay a 0.95 mille property tax, or about $95 per year on a property assessed at $100,000. The funds would go to a mix of service increases for SMART across the county and existing local paratransit agencies in the rural and exurban opt-out areas. The proposal aimed to maintain existing services, including the politically popular rural services, while running more buses, building a connected countywide system, and ensuring that every community contributed its share. It would also take advantage of recent federal stimulus bills, providing local capital funding that federal aid could match — an opportunity to buy new buses and replace old ones beyond their service life. The Commission would meet again on August 10 to approve the bill and place the question on the November ballot.

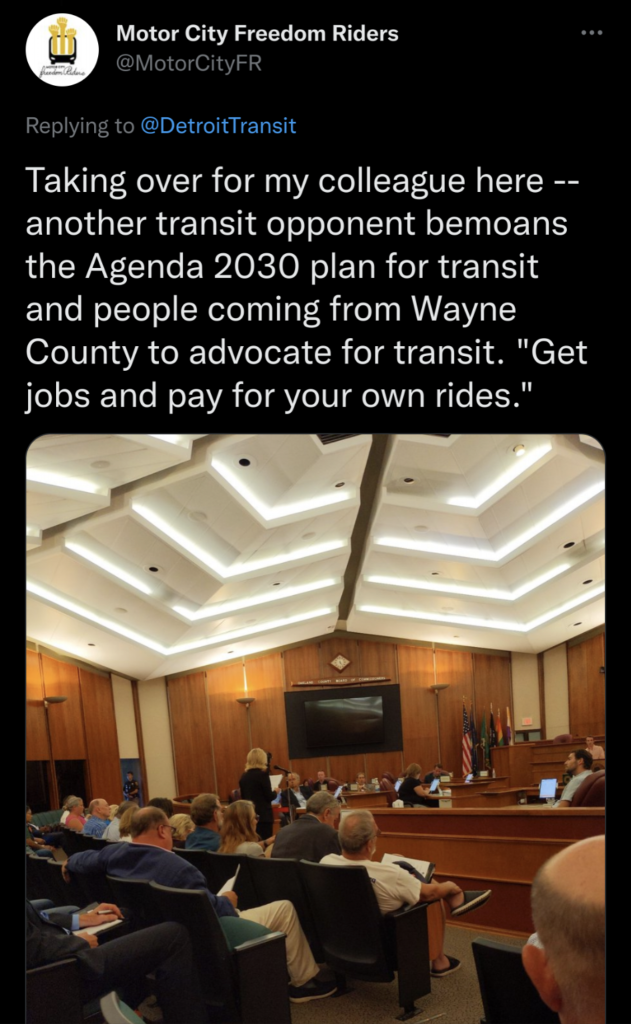

On the 10th, pro and anti-transit advocates packed the Commissioners’ chambers. The anti-transit protesters, uniformly old and white, made arguments ranging from basic to bigoted and bizarre. Most bemoaned the tax increase and the lack of an opt-out clause. A few complained falsely about transit funds going to Wayne County aka Detroit. Milford Township Supervisor Don Green asked why those with transportation needs didn’t just ask their friends and family. (Who doesn’t love begging for a ride every day just to get to work?) Many referenced the transit measure as a plot involving the World Economic Forum or Agenda 21, both staples of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories about global elites taking over the world. An anti-transit protester asked your blogger who had paid him to attend. (If any globalists, Chinese Communists, or people from Wayne County want to pay me to raise taxes and attack and dethrone God, my Venmo is @calleywang).

On the other side, a diverse coalition of transit supporters endured heckles from the opposing side and spoke passionately about the social and economic, and environmental benefits of an actual countywide transit system. Transit riders, aspiring transit riders, youth with disabilities, environmentalists, and just ordinary citizens gave shared their own personal connection to the countywide transit measure.

After nearly two leg-numbing hours of public comment, deliberation began. The minority caucus made repeated attempts to table the measure, reduce the tax amount, or reintroduce opt-outs. All attempts failed along party lines. In the final vote, a bipartisan majority of the County Commission passed the resolution for countywide transit 13-7, with two Republicans and all Democrats voting in favor. Republican Michael Gingell, representing an exurban district that was mostly opted out, explained his reasoning for voting yes, to boos from the anti-transit crowd. He did not like the proposal, but with the Republicans in the minority, didn’t have the votes to stop it. It was better to vote yes and ensure that the money was spent wisely as intended.

Meanwhile, across town at The Crofoot in Downtown Pontiac, advocacy group Transportation Riders United and the city of Pontiac held a Transit Town Hall event. Advocates and supportive officials spoke with members of the public on the need for expanded public transit. Commissioner Woodward was supposed to be a keynote speaker but he was, of course, busy passing the relevant legislation. The ballroom erupted in cheers upon receiving word that the countywide transit measure had been place on the ballot.

Thomas Yazbeck, an advocate at TRU, began his interest in transit in his hometown of Rochester Hills, an opt-out community. What began as a campaign to bring the bus to his city became part of a larger countywide struggle, which has finally advanced after decades of false starts. “I think this is a remarkable achievement even at this early stage,” he said. “The fact that it was placed on the ballot and got Republican support is very historically significant.”

Next Steps: Convincing The People

The next step for advocates is to get out the vote in November. With strong support in the existing densely populated opt-in areas from voters, the odds seem favorable. Yazbeck believes the main challenge will be to convince voters in middle ring of suburbs. These suburbs are fast-growing, affluent, and populous — not sleepy rural townships. Once bedrocks of suburban conservatism, they are now politically divided between Democrats and Republicans. Because of their wealth and influence over the rest of the metro area, he believes that winning here will be crucial.

This task is difficult but doable. When opt-out middle ring suburbs like Rochester Hills and Novi voted on the Regional Transit Authority measure in 2016, they were almost evenly split despite having no mass transit and a sclerotic campaign by the RTA. A stronger campaign can convince these “swing” areas of the new transit program’s benefits.

It is still a controversial topic in Trumplandia. It’s something we saw in Auburn Hills, where the city council voted to reject the will of the voters by saying that, no, 75% of people voting in favor of transit doesn’t mean we should keep funding transit. (Hey, also? Apparently that vote was illegal and invalid! Whaddaya know?!)

Are Gas Prices A Favorable Tailwind?

One might note that transit is probably a great value proposition when gas prices are near all-time highs. (They weren’t, in most cases, surpassing all-time highs, but American popular memory only extends about 3 years into the past, so we’ve forgotten about 2008. Either that, or the fact that I have muted the term “grim milestone” from all of my social media means that I missed that Forbes article. It’s really not a grim milestone. Gas prices are too low and have been for, well, basically ever. But I digress).

Historical research shows that transit ridership usually picks up as gas prices increase. The correlation is complicated and it’s not super stark because oil is a thing that economists say is “demand inelastic.” This means that prices can go up, but demand won’t buckle unless the prices go way up, or if the prices spike in a very short time frame. But the correlation is generally positive. It’s possible that transit ridership would increase more with sustained periods of increased gas prices. But I guess we’ll never know, because President Brandon moved the gas prices lever back down. Or whatever.

It’s also complicated because transit service cuts during COVID mean that even with gas prices, transit ridership is still far lower than it was pre-pandemic. The myth of “public transit as superspreader” persists, even though numerous studies have addressed and disproven this myth. This is another way of saying that gas prices going through the roof didn’t incentivize transit ridership as much as planners thought they might. Gas is still frankly too cheap in the opinion of the Handbuilt editorial board, and with cheap gas, the push for incentives for alternatives is much more muted than if gas were much more expensive.

Michiganders are tired of seeing their tax dollars squandered on dumb stuff. “Just another lane, bro, I swear, it’ll fix it this time!” says MDOT each year.

The Hot-Button Issue

Transit spending in Southeast Michigan, though, is a diabolical political calculation. Because in a world where increasingly everything seems to merit a dismissive, ridiculing “haha” react on Facebook, the very idea of a value proposition is increasingly elusive to many stakeholders. In other words, an electorate that is increasingly hostile toward, well, basically anything, especially the big bad gubmint, suggests that it’s gonna be hard to get voters in places like RTA opt-out communities like Novi to suddenly believe in, you know, the value of having an actual society. Never mind that those people already pay thousands of dollars in taxes for things they already don’t use. Like, I don’t know. Maintaining the Mackinac Bridge, perhaps. Or building roads in distant corners of the state. Or the defense industrial complex.

But again, that’s not what this is about. Michiganders are tired of seeing their tax dollars squandered on dumb stuff. “Just another lane, bro, I swear, it’ll fix it this time!” says MDOT each year. While inking corporate welfare packages to promote new factory development related to the Big Two and a Half’s push for vehicle electrification, Governor Whitmer has stalled the advancement of the I-375 removal project, which was a popular proposal in Detroit that would have attempted to right a historical wrong of demolishing a majority Black neighborhood to build a vroom vroom strip so suburbanites could get to work and leave the city faster. Of course, I-375 is off the radar of most suburbanites, who don’t use it. They do use the big highways, of course. But many of them– including the vocal opponents at last Wednesday’s meeting- seem determined to dig in their heels on the transit issue.

It is straight out of the Trump playbook of uttering impassioned but ultimately demonstrably false claims about transit– that it will attract dirty poor people who will commit crimes, they say. Another take is that it’s “too expensive,” which is why Kevin McDaniel and a majority on the Auburn Hills City Council ostensibly cast their procedurally-illegal vote against remaining in the system. $150 a year to fund modern infrastructure is too expensive, but thousands of dollars per year in corporate subsidies aren’t. Apparently.

MDOT: Rebrand And Replace. Some Ideas From The MAP Conference.

The Un-RTA SMART Millage

Suffice it to say, the vote last week marked an important moment as we think about what the future of the RTA might hold. Going back to the patchwork question, the Regional Transit Authority is a sort of intergovernmental agency, hobbled by legislative fiats that were designed by anti-Detroit politicians like Brooks Patterson (read: Brooks Patterson Is Dead, But Rock And Roll Will Live Forever). The RTA isn’t the same as SMART, which administers the suburban bus service. RTA has led its own ballot initiatives in the past, which have failed. They will, in all likelihood, fail again, barring having huge, public support from large employers like DTE, GM, Ford, or Quicken. But the vote last night at least sets up the possibility of future success for the RTA.

It’s a small step, certainly, with a meager seven million dollars for capital improvements across the entire county, and just over $20 million for additional transit operations. But combined with a relatively pro-transit federal administration in Washington, it’s possible that the passage of a universal SMART millage will open the door to a much more definitive, unified future for infrastructure investment in Southeast Michigan.

Handbuilt transit correspondent Calley Wang contributed to this article. Calley volunteers with the Motor City Freedom Riders and Transportation Riders United, two Detroit-based transit and mobility advocacy groups. Check out Drawing Detroit for more on mapping of this issue. Stay tuned for more coverage of the SMART millage vote later this year, and follow Handbuilt’s ongoing series on infrastructure, mobility, and transportation.