“Detroit: Become Livonia” – Mike Duggan

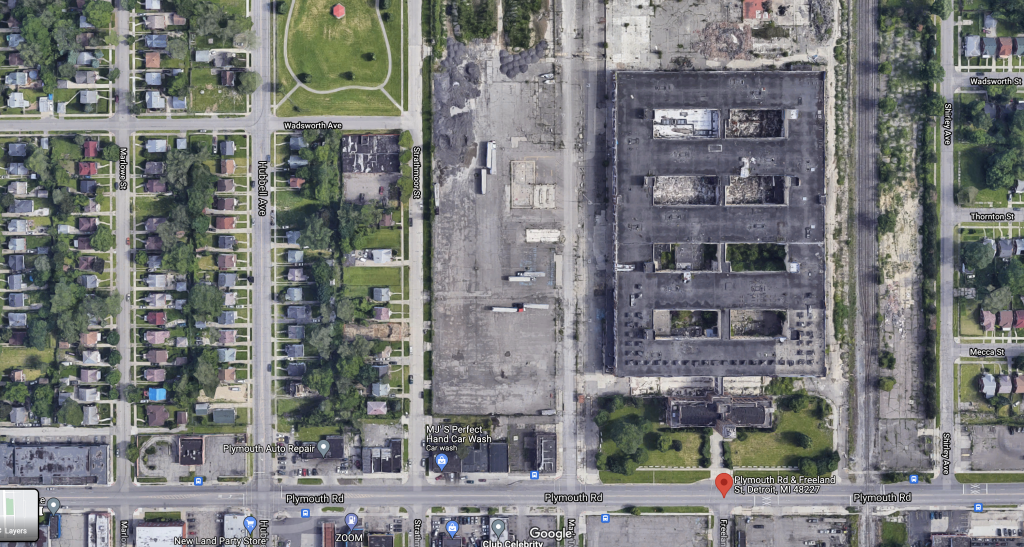

I was frankly unsurprised to read Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan’s announcement that the city is going to sell the disused headquarters and former factory of the American Motors Company on the city’s west side, to a Missouri-based warehouse developer. Duggan argued that it’s not only a great solution for creating jobs, but also a solution for clearing blight. He actually went so far as to use the term “ruin porn” as a justification for demolishing an architecturally notable building that contributes significantly to the city’s rapidly vanishing industrial heritage. The endgame here appears to be to turn Detroit into the suburban hellscape of Livonia that the mayor came from, if you’ll pardon my video game reference here.

BREAKING: @MayorMikeDuggan announces the former AMC Headquarters on Plymouth Road in District 7 in #Detroit will be demolished for a new development by NorthPoint. A shame it won't be redeveloped. It was built in 1926 for Kelvinator. #preservation pic.twitter.com/TtGWeqwPvr

— HistoricDetroit.org (@HistoricDET) December 9, 2021

Chrysler (as Chrysler, before it was DaimlerChrysler, before Fiat Chrysler, and before its present incarnation as Stellantis— who can keep it straight?) bought the remains of AMC in the 70s and eventually relocated the remaining staff in the building amid the bankruptcy-era reshuffling of 2009, meaning its abandonment is, well, relatively recent. AMC itself had bought Nash-Kelvinator, a hybrid of Nash Motors (1916-1937) and Detroit-based appliance manufacturer Kelvinator. There’s an interesting and tangled web woven by these predecessors of AMC, as the early Kelvinator’s startup money was actually financed by an automotive executive from Buick– and Kelvinator went so far as to actually develop an entire neighborhood in Livonia, of all places, in the 1920s and 1930s, as a sort of demonstration project for residential air conditioning and refrigeration.

we used to build stuff in this city and now we just have parcels upon parcels of suburban-owned, derelict real estate that collects pools of motor oil underneath busted old cars.

This is the city’s history– being replaced by warehousing that involves less in the way of good, skilled jobs in manufacturing, and more in the way of poorly-paid jobs in distribution of imported parts and other products. For Nash-Kelvinator-AMC, it’s the kind of history that is lost generally over the course of decades of corporate successes, failures, mergers, and acquisitions. But for Detroit, it’s an endemic issue. Wrote Paul Jones III eloquently in the Metro Times:

For almost a decade, this mayor has shown a sustained commitment to the underdevelopment of sites like these as his main economic development tool. By demolishing our city’s architectural gems and replacing them with cookie-cutter, polluting industrial sites, we further devalue the places and people that make our city special. Through demolition, we completely eliminate the chance for Detroiters to imagine unique futures based on adaptive use models that have proven successful here and elsewhere. By replacing them with the types of jobs the Duggan administration has attracted, the city is actively tying Black Detroiters back to the same volatile manufacturing economic cycle that has always disproportionately impacted our households and wealth.”

It may well feel less relevant when you’re driving by an abandoned building and, rather than wondering what used to be there, you’re instead wondering why there is so much blighted property in this city. But when that building is demolished, you don’t get to wonder about what was there before. You just see some suburban hellscape of black asphalt and stamped metal siding that will make Detroit indistinguishable from the mayor’s native Livonia. Jones, himself a planner, connects the architectural parameters of the space to the nature of the employment that is located there.

We can look well beyond the site itself to find examples of how this has played out in the past decade since Chrysler’s departure.

Car Graveyards vs. Car-Building Graveyards

As you probably know, I’m a big fan of considering the broader spatial or economic context of any intervention in the built environment. This is perhaps a notable contrast with our beloved mayor, who just loves to plop down parking lots in the middle of neighborhoods, because progress. It’s worth considering in this case, though. The AMC-Nash-Kelvinator building has the unusual orientation of fronting on a street that itself serves as an automotive-ish corridor. Freeland Street, discontiguous and interrupted a number of times in its north-south trek through the west side, runs a few blocks here before it gets interrupted by a rail siding.

During the 45 minutes or so I worked in the city’s building department, we had a targeted enforcement campaign for what we called the “auto project.” The auto project focused on automotive uses. The irony of the city’s industrial decline was that a large number of former factories for cars and car parts had been turned into things like body shops, junkyards, chop shops, and everything that blurred the line between these three.

It’s an interesting concept, whether you take a doom-and-gloom, academic angle, that this perhaps presages a catabolic collapse of society, or whether you simply think it’s notable that we used to build stuff in this city and now we just have parcels upon parcels of suburban-owned, derelict real estate that collects pools of motor oil underneath busted old cars.

Junkyard Slumlords, Perhaps A Uniquely Detroit Phenomenon?

Freeland Street in particular stretches directly south, basically from the front door of the AMC building, past a sort of postindustrial shantytown of car-related businesses operating in various levels of illegitimacy. At least a couple of these businesses are owned by Behrouz Rashidinejad, a Belleville-based junkyard slumlord. I’m not kidding. In addition to operating his own junkyard in Belleville, Rashidinejad leases out junkyard real estate to entrepreneurs all over the city and has been the focus of extensive enforcement efforts, even pushed fairly proactively by the likes of the generally utterly inept management of BSEED. Have you ever seen Star Trek Voyager? Rashidinejad is one of the garbage aliens. Straight up.

Rashidinejad was the registered agent or owner of a number of different corporations, including Beam Properties, LLC, which owns property on Freeland Street.

Cyclical Manufacturing Economy vs. The Less-Than-Lucrative Economy Of Waste and Salvage

I guess you could argue that there’s a lot about the waste and salvage economies that is, in fact, interesting– and beneficial for society. Parts Galore, a Tony Soave original on West Warren Avenue, for example, is kind of like Amazon but for wrecked cars and their parts. The business occupies a multiple-acre site on the city’s west side. You go in, you pay an entrance fee, and you get to basically disassemble whatever you want from a car and then buy it for scrap weight. It’s especially useful in a case where you need an obscure part that the dealership can order for you and install for $1700, but that you can extract yourself from a totaled model for a couple of hours and the cost of a quarter ounce of Gojo to get the grease off your hands. It is even possible to find a “picker” and pay them a nominal fee to extract the part you need.

However, while Parts Galore is a generally-legitimate business, there are plenty that are not so illustrious. Rashidinejad, for example, subleased out a junkyard in what I will call the Lower West Side, to an entrepreneur who had to figure out how to not only maintain the site’s crumbling industrial buildings– while figuring out how to turn a profit off stacks-upon-stacks of scrap cars (not allowed by city code) in an age when scrap metal was dirt cheap.

In 2018-2019, it was more expensive to tow a car than it was to scrap it, unless you could scrap a catalytic converter, which contains a hefty sum of precious metals like palladium and platinum. This was a product of depressed steel prices, which, in scrap terms, have roughly doubled since that time. Specialized, intact parts– things like electronics, seats, seatbelt tensioners, transmissions, or even engines- are the one part that actually provide real value for a scrapped car. But if it costs you $50-100 to tow the thing, then hundreds. of dollars to comply with city requirements for licensing– plus making sure the buildings on your site aren’t falling down- it’s easy to understand how this isn’t a lucrative business, let alone an easy one.

Toward Long-Term Value

Interestingly, Freeland Street has some stretches of relatively stable real estate valuations. This is probably the product of its heritage as a well-used industrial corridor. It has direct rail access, decent highway access, and, overall, pretty good market access. A quick look through BS&A records show buildings that sold for $100,000 in the 1970s or 1980s and sold for even higher numbers in the 2000s or 2010s. This is unusual in a city where the average sale value has plunged over the past half century. Translation? There’s value in considering clusters of even small industrial or light industrial uses.

Am I gonna buy a car from one of these people? Absolutely not. Been there, done that, not doing that again. But there are ways that the city can gently nudge folks to maintain their properties in working order while also making sure they’re not doing anything overtly illegal (I am familiar with at least a few stolen cars that have ended up in this corridor). There are also unrelated, non-automotive uses in this corridor. This is the kind of thing Duggan should be emphasizing, not just figuring out who is gonna build a car parts warehouse.

I suspect Duggan will get his way on this, just as he gets his way on most other things involving development and the transfer of land or public wealth to private, out-of-town developers to build shitty, suburban-style projects that will themselves be out of business within a few years, before which time they’ll provide Detroiters with poverty wages while enjoying massive public subisdies. Flex-N-Gate? Amazon? Remember Sakthi Automotive (RIP)? It’d be interesting to consider alternatives.

For my part, and lest someone think I’m just a complainer who never comes up with solutions for all of these things I find ever so objectionable, I’d be happy to volunteer my trusty Matterport camera to provide a would-be developer with a full set of plans for the AMC building. Let’s keep the city’s history intact and collaboratively envision a new context for it. Freeland Street, with a well-established basis of industrial value– and a long history of manufacturing- doesn’t have to look like it does now. But it’s not getting any better by simply turning Detroit into Livonia.

I did not bother to reach out to the city for comment, but I did reach out to NorthPoint, and I had not received a response as of the time of publishing this post.