In This Most Righteous Struggle: The St. Louis General Strike of 1877

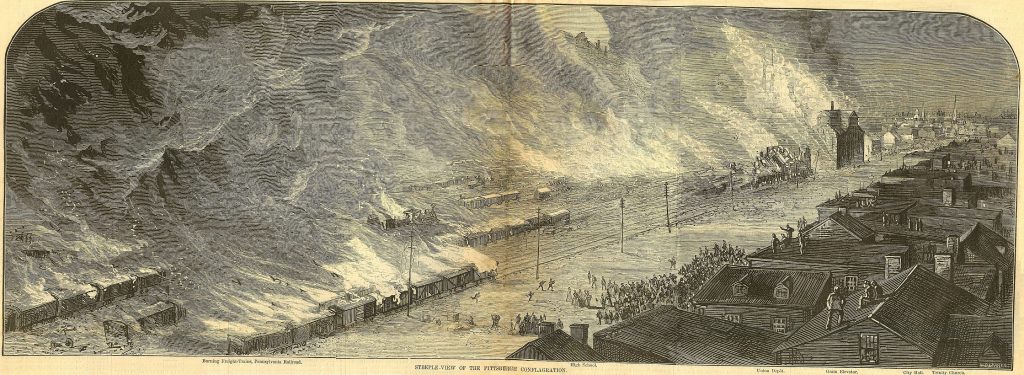

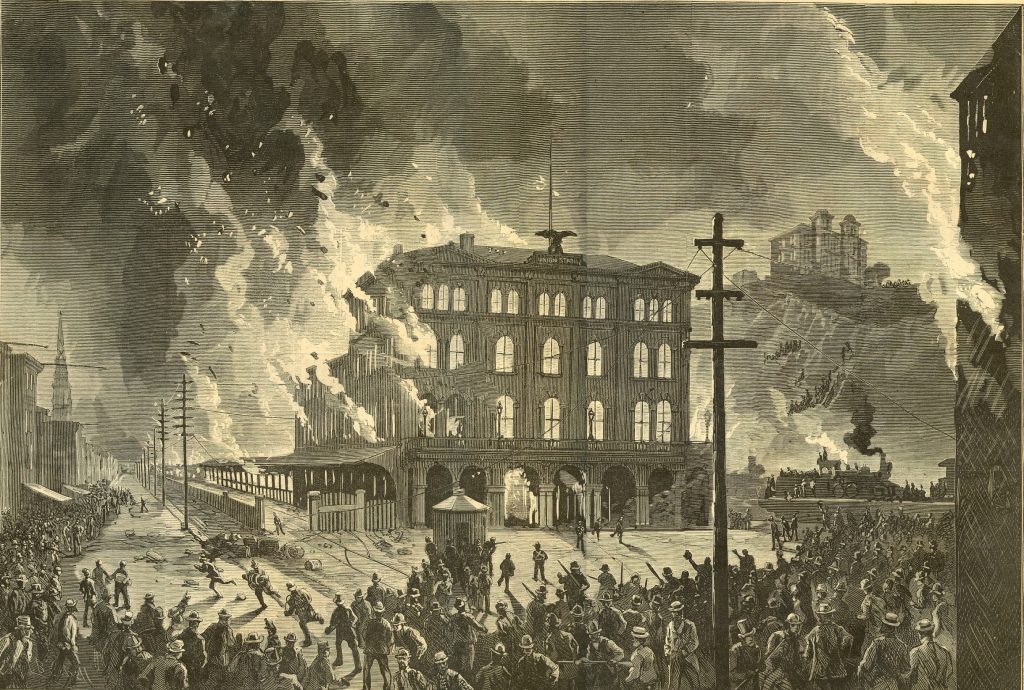

Long before the era of stable monetary supply and central reserve banking, the US economy was prone to catastrophic disruptions. These were not just a product of an inability of the federal government to centrally regulate, but were more a product of a complete lack of any regulating or moderating power whatsoever alongside the breakneck expansion of the built environment, industry, and railroads in the 19th century. One oft-forgot milestone in US history is that of the St. Louis General Strike of 1877, which started 144 years ago today. The St. Louis strike was part of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, which lasted months and took place across what we now think of as the Rust Belt. Places we’ve largely forgotten– Shamokin, Reading, and of course, larger cities like Pittsburgh and St. Louis- were the flashpoints for this popular uprising, which saw widespread destruction of property and state violence against workers.

The General Strike– one of the first in the United States and arguably the first notable mass labor-esque action since the labor-adjacent revolts of the early 19th century, which were more agrarian in nature- began as a protest against working conditions precipitated by a perfect storm of economic conditions. The Long Depression of 1873, which continued, depending on how you figure it, for a couple of decades, saw a substantial slowdown following the post-Civil War industrial boom in the US. There was a lot of complicated stuff going on– the US ditching the bimetallic currency standard, for example, or rampant problems in corrupt and speculative railroad development in the American West. Suffice it to say, the workers got screwed. So it goes.

The Strike Begins

In East St. Louis, the Marxist United States Workingmen’s Party issued a manifesto:

- Whereas, The United States government has allied itself on the side of capital and against labor; therefore,

- Resolved, That we, the workingmen’s party of the United States, heartily sympathize with the employes of all the railroads in the country who are attempting to secure just and equitable reward for their labor.

- Resolved, That we will stand by them in this most righteous struggle of labor against robbery and oppression, through good and evil report, to the end of the struggle.

Workers blocked passenger and freight rail on various routes in and out of St. Louis, then one of the most important rail hubs in North America. Engineers, machinists, and laborers all participated in the strike, which resulted in widespread destruction of industrial property, railroad facilities and rolling stock, and a days-long, interstate protest movement, as strikers coordinated across the Missisippi River and the whole way to Chicago, where a particularly violent strike was on going.

The labor actions emboldened the federal government to formalize the National Guard, which was then a largely disorganized group of militias that had existed, not under the same name, since the era of English colonization. While the National Guard wouldn’t be completely formalized for another few decades, the strikes provided an impetus for the federal government to figure out how to deputize citizens and deploy them to use force in, ostensibly, maintaining the peace.

Pro-Capitalist Business Forces Revolt

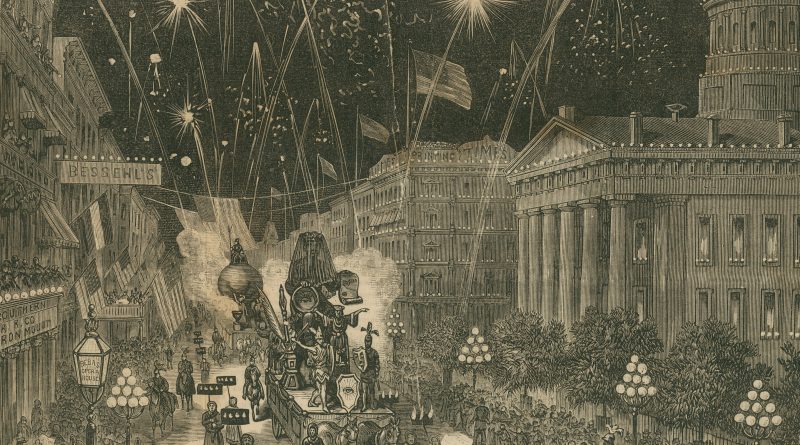

The following year in St. Louis saw the birth of the Veiled Prophet Ball, a debutante event sponsored by, among others, a former Confederate general under the auspices of the Veiled Prophet Organization, a fraternal organization. The event was organized by powerful business interests in St. Louis as a way of establishing and normalizing the idea of popular, pro-capitalist order in the aftermath of the revolution. Organizing a massive parade event, it has also been argued, was a way to show up the workers. “Whose streets? Our streets!” so much has been chanted, variously, by protesters and even by St. Louis police in the past 12 months.

So, of course, it has to be complicated by the Mound City’s unique position between the South and the North, and the East and the West. The event’s costuming bore a striking resemblance to the white robes of the Ku Klux Klan. Historians have noted this similarity, and it’s not exactly a stretch given the ex-Confederate connection.

The bizarre, orientalizing, mysticism of the movement– referring to the Veiled Prophet of Khorassan- is certainly not something completely out of place for the 19th century. In a similar vein, the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, a.k.a. the Shriners, originated just seven years prior. The name of this fancifully imagined Veiled Prophet of Khorassan— don’t let the Klanly robes fool you- is apparently a reference to Lalla Rookh, a similarly orientalist romance poem by Thomas More from 1817. The historic veiled prophet was none other than Al-Muqanna (هاشم), who was kicking it in the 8th century. More’s character of Mokanan was supposed to be modeled after Muqanna, who himself fancied himself a prophet in creating a hybrid religion of Zoroastrianism and Islam. Beginning in the 1870’s and continuing to this day, the Shriners similarly embraced the Fez and the scimitar as emblems of their occult, oriental brand standards.

Implications for the Future of St. Louis

The VPO and, no doubt, its accompanying imagery and symbolism, was thought to also be inspired in part by the Mistick Krewe of Comus in New Orleans (ever been to a Mardi Gras parade?), which had originated two decades prior. (St. Louis has the second largest Mardi Gras celebrations in the United States, although you wouldn’t know it from how the shrinking city gets routinely ignored in popular discourse). The Veiled Prophet Ball suffered numerous protests during the civil rights era and the 1960’s and 1970’s countercultural movements, including some notable and lively protests by a group called the Action Committee to Improve Opportunities for Negroes, or ACTION.

The event itself was rebranded in 1992 as Fair St. Louis, but continues to this day in some format. Strange times. Strange town.

Connecting with the Missing Links of History

This is the kind of history you get from Howard Zinn. But it’s not from these states that want to restrict access to education about American history, as Texas just did by banning the teaching that the KKK was a bad thing. One wonders where the limits of human decency are in an era when red state legislators insert themselves into basic questions of history– of which they apparently grossly lack understanding. It’s not any sort of Rubicon that they are crossing, though, because red states have been on their bullshit for, well, ever. Missouri and Texas are, of course, two peas in that same pod.

Do these violent labor strikes mean that American society is morally bankrupt and needs to be dismantled and replaced with a central Soviet? Absolutely not. At least, that’s not what I’m hearing when I hear Americans clamoring for access to affordable health care, clean air, quality education, consumer protections, and infrastructure investment. What they do mean is that the labor movement has an important history that connects with every American community, and, indeed, with every American struggle. We don’t learn anything when we don’t learn these stories.

The labor struggle is itself a very American struggle however you slice it– whether you’re thinking about early American colonists fighting the British, slaves fighting for freedom, native and indigenous people fighting for their own land against the anti-colonial-turned-colonizing forces, or, really, any group fighting for greater recognition and equal rights. It’s a fight that continues to this day, no matter how much they try to legislate educating about it in, ya know, shithole countries. Like Texas. Sorry not sorry.

Everyone has stories like that of the 1877 St. Louis general strike. It’s important that we don’t forget these histories.