Dreams of Better Transit Signage. How Legible Is Your City?

Martha Connell and I have been scheming up some ideas for what transit signage might look like in a more legible city after her piece on the future of the QLINE. For the part of the Gilbert Express, six weeks after Martha’s piece, the QLINE is still not running. It’s been nearly 18 months since service was shut down. So, as Detroit’s own beleaguered bus agency is only able to deliver around 70% capacity at the moment given a shortage of (grossly underpaid) drivers, we’re thinking instead about what we can do to shift the culture of how we move through urban space. In other words, how do we get around? How can we make it easier for people to understand how to get around? People take the QLINE because the signage and stations jump out at you. The train itself is also May Day red, yes, but the stops are well-marked and independently illuminated.

What Is Legibility?

The idea of “legibility” isn’t terribly new. I might be wrong, but I’m pretty sure that the term itself goes back to the beginnings of modern city planning, which was more focused on humans and how humans interact in space (Planning 2.0, Jane Jacobs, Kevin Lynch, etc.), rather than earlier iterations’ focus on the spatial, geometric parameters of cities (Planning 1.0, like, Camillo Sitte, Baron Haussmann, arguably City Beautiful, etc.). If you go back to Camillo Sitte, he writes about stuff like how to think about planning of intersections around “viewsheds,” i.e. “the area whence a certain thing can be seen.” Haussmann was into this, too, and that’s why the monumental boulevards of Gay Paree typically end in these bombastic roundabouts with monumental equestrian statues and giant arches and what not. Crafting State power via citycraft! Richard Sennett shit, ya know.

Put in less academic terms, the urban fabric tells us what the State wants us to know, and this contributes to legibility directly. We’ll get to signage in a minute– don’t worry. Rural American towns built around the courthouse square or train station square presented visions of centralized state power (courthouse) or the centrality of economy (rail). The suburban hellscape of most American suburbs indicate, for example, that the State doesn’t care about you, your safety as a pedestrian, or the natural environment.

Why An Illegible City?

And a city that doesn’t invest in transit signage? Well, it’s not that the city can’t afford it, certainly– not in the United States, at least. If you look at pictures of city streets in so-called “third world” countries, you’ll note a lot more informality of systems. There might not be as clearly marked things like traffic lanes, intersections, or bus stops. These things are generally products of wealthy countries with strong apparatuses of state power, so the informality here is because of an insufficiency in capital and state order to produce these systems. No doubt this might be confusing for a North American visitor to, say, Angola. But it would be understandable when you’re looking purely at numbers like GDP. (In spite of this challenge of legibility, informality also lends itself to all manner of innovative and entrepreneurial things that are precluded by the strict order of wealthier economies, too! But this is a story for another day).

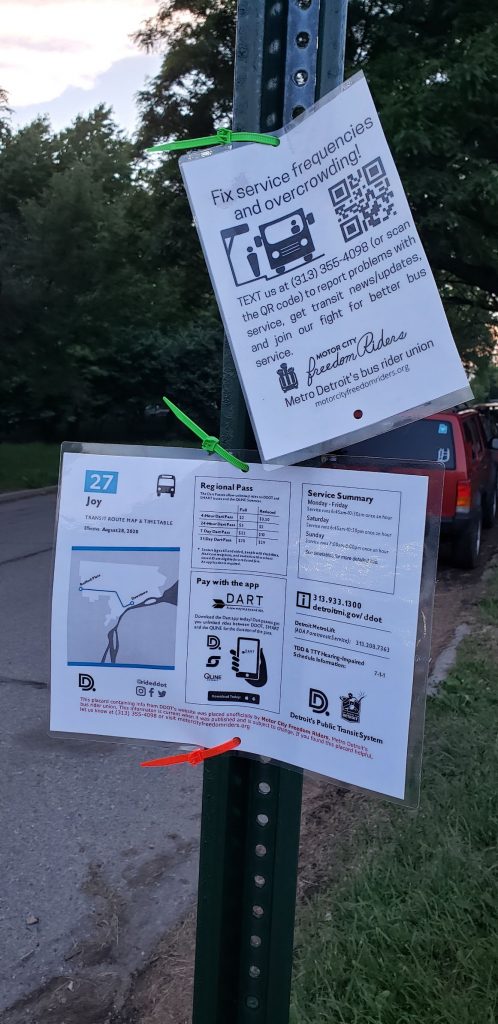

…anything would be better than what we currently have. It’s just a question of whether the city is going to step up to do it– or whether it’ll be folks like Calley out there, hitting these mean streets with zip ties and laminated placards.

In the United States, though, it’s a conscious choice for cities to mess this up. In Detroit, the poor signage communicates that the city doesn’t prioritize alternative modes of transportation. In the words of a wise Twitter commentator, whose quote I included in my graduate thesis: “It’s the Motor City, fucking dumbass. Buy a car.” But, of course, as will be noted by former DDOTer Mikki Taylor-Hendrix in the upcoming SISE podcast, about a quarter of Detroit households don’t own a car. So it seems to make sense that we should want to make these systems easier to understand.

Requirements of a legible system

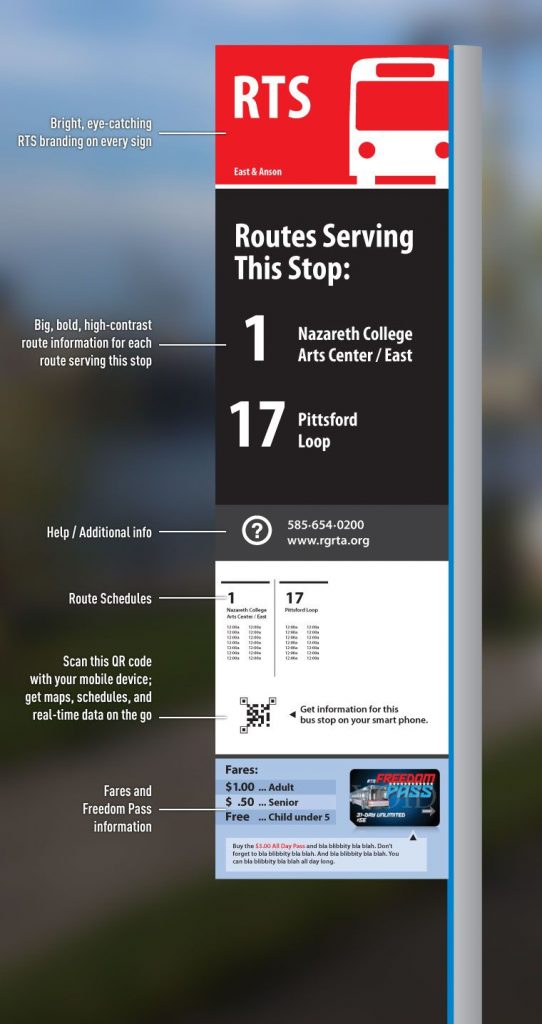

- Transit stops must be readily identifiable as such. I mean, we really have to do better than just a sign that says “BUS STOP.” Come on.

- Signage must tell riders about the route in question. There’s a question about “how much” they must communicate (below).

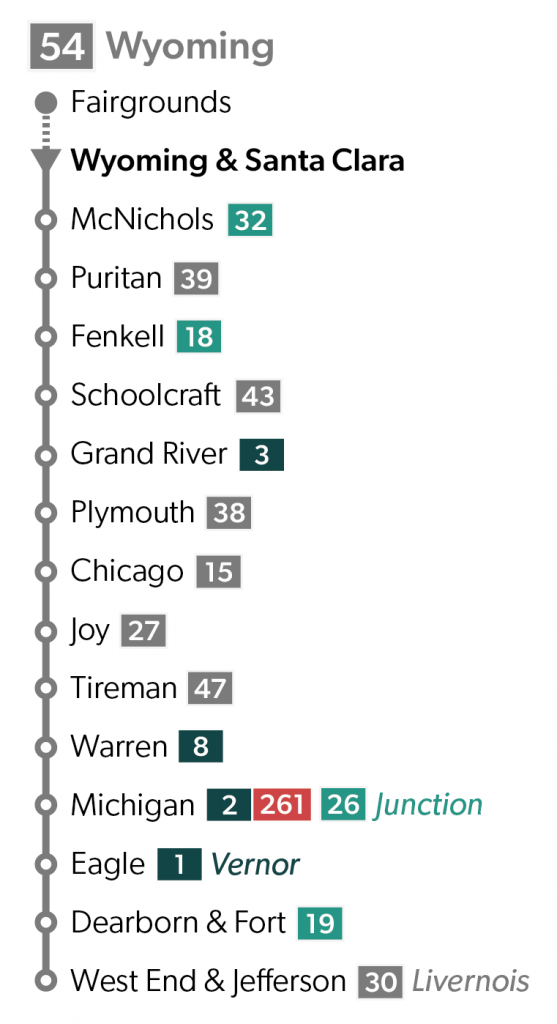

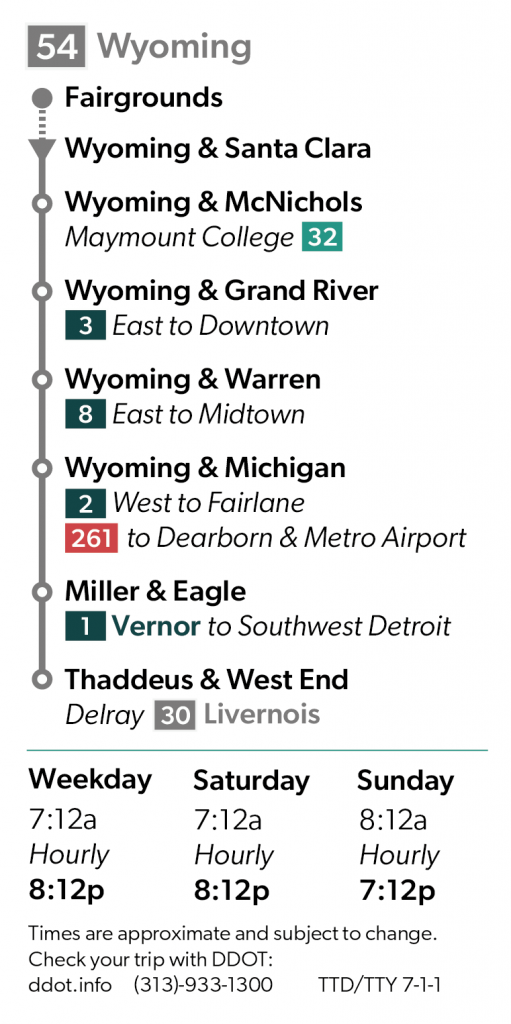

- Route data should indicate transfer points and, probably, general geography. I noted this issue in WMATA when I was in DC, where it says in only tiny text that such-and-such side of the platform leads “downtown.”

- General arrival and departure times. This is usually categorized by language like, “service every 20 minutes, M-F day, hourly overnight,” or what have you.

- Route data should be sufficiently detailed, but not so busy as to confuse riders. This becomes an issue in the below image (middle).

How to fix it?

As in the picture at the beginning, some advocates have taken to putting up their own signs. That seems like a start–in the absence of action from the city. DDOT bus stops these days come in two formats. One is like the green and yellow sign in the first picture, showing “BUS STOP” and nothing else. More advanced ones, installed only in the past couple of years, show the route, which tells us a limited amount of information. Martha and I schemed up some ideas for what a better solution would be. It needs to be cheaper than the likes of the fancy, wi-fi enabled Australian sign we showed before. Otherwise, the city is unlikely to invest in it. (After all, it’s a transit sign, not a billionaire-owned parking lot– come on!).

It’d be possible to install a permanent, sort of cover panel on these regular, old, corrugated steel poles, that would show you a full range of data about the buses. Heck, you could even put a solar-powered light on top to illuminate them at night. The bottom line, though, is that anything would be better than what we currently have. It’s just a question of whether the city is going to step up to do it– or whether it’ll be folks like Calley out there, hitting these mean streets with zip ties and laminated placards.

What do you want to see in transit signage? What would compel you to get around with transit if you don’t already? Write to us! Learn more about transit justice efforts in Detroit from the Motor City Freedom Riders and TRU. Remember to support independent journalism!