Rivers and Roads (and the World’s Largest Dam Removal)

THE ELWHA RIVER HAS BEEN FLOWING ON THIS LAND since long before it was called the Olympic Peninsula, or Washington, or the United States. And the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and other neighboring Coast Salish tribes have been interacting with the Elwha since long before then too. It’s a river that words can only begin to describe. Starting in the Olympic Mountains and ending in the Salish Sea, it meanders through rugged peaks, alpine meadows, and emerald forests. The Elwha appears to possess an energy of its own. Even when the sky is cloudy and dull, the Elwha’s waters shine clear and bright.

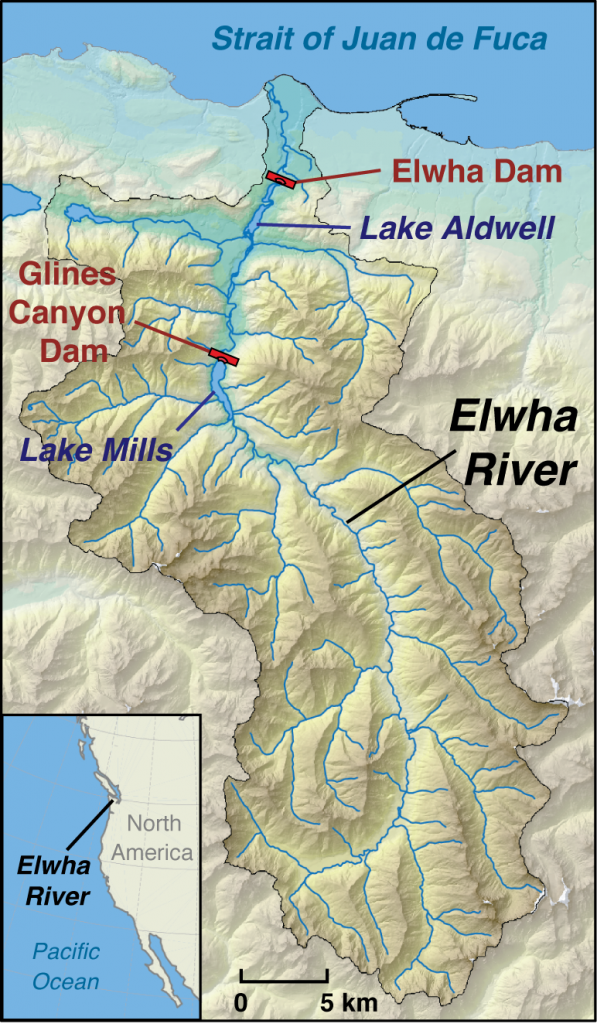

The Elwha Dam and the Glines Canyon Dam were constructed on the Elwha in 1913 and 1927, respectively. They changed everything. In the largest dam removal in the world, the same dams were removed in 2011 and 2014. The dam removals again changed everything.

The dams were constructed to supply hydroelectric power for a pulp mill and the nearby city of Port Angeles. Though they were successful in this regard, they caused many ecological harms. One of the dams’ most significant harms was to salmon, which are essential to the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe. Salmon are born in freshwater, feed at sea, and return to their birthplaces to reproduce and die. The dams blocked sediment from flowing downstream, without which the riverbanks and shoreline eroded. This erosion decreased the amount of habitat suitable for salmon to release their eggs. Additionally, the salmon were not able to return to their birthplaces because the Elwha Dam blocked their path five miles in (compared to more than 70 miles of open river before the dams were constructed). Restoring the salmon by reversing these effects was the main push to remove the dams.

Changing Ecosystems, Unchanging Infrastructure

If we think of ecosystems as a specific combination of organisms and their environments (a river, for example, is part of an ecosystem), then ecosystems are really four-dimensional (rather than only three-dimensional). They not only exists in a specific space, but also at a specific time. All this is to say that the pre-dam construction, post-dam construction, and post-dam removal ecosystems are different ecosystems. They exist in the same space, but at different times.

Most infrastructure in the area was built after dam construction for the post-dam construction ecosystem. Then the dam was removed, and the ecosystem changed. The old infrastructure did not.

By regulating the Elwha’s flow, the dams made high flow events less high and reduced the Elwha’s migration across its floodplain. The high flow events and river migration after the dams were removed were incompatible with the old infrastructure. Olympic Hot Springs Road, an 8.2 mile road that meanders along the Elwha in Olympic National Park, bore the brunt of this incompatibility. Since the dams were removed, the road has frequently washed out. Olympic National Park constructed four temporary bridges over the washouts, but none remain today.

The road is now inaccessible by vehicle. However, cyclists and pedestrians can still use the road (and a trail to bypass the washout). This has its advantages: there is less traffic at the previously busy Glines Canyon Spillway Overlook (the site of Glines Canyon Dam) and on previously busy trails. And, in my opinion, there’s a certain dystopic enchantment to the washout itself—the powerful river gushing over crumbling asphalt and ragged, moss-covered trees mirrored in glassy pools adjacent to the road. But the washout also has its disadvantages. Less traffic means fewer people are able to see what was once accessible by road or a shorter hike. And this access is precisely the mission of the National Park Service. Moreover, without road access, monitoring, evaluating, and managing ecosystem recovery post-dam removal is far more difficult.

Was There Another Way?

We understood many of the effects of dams on rivers (such as regulating high flow events and reducing river migration) before the dams were removed. However, being the largest dam removal project in the world, we did not understand the effects of removing such large dams. As a result, Penny Wagner, Olympic National Park Public Information Officer, told us, “The modeling [of the effects of removing the dams] did not tell us that the road would absolutely wash out. It was only one potential scenario.”

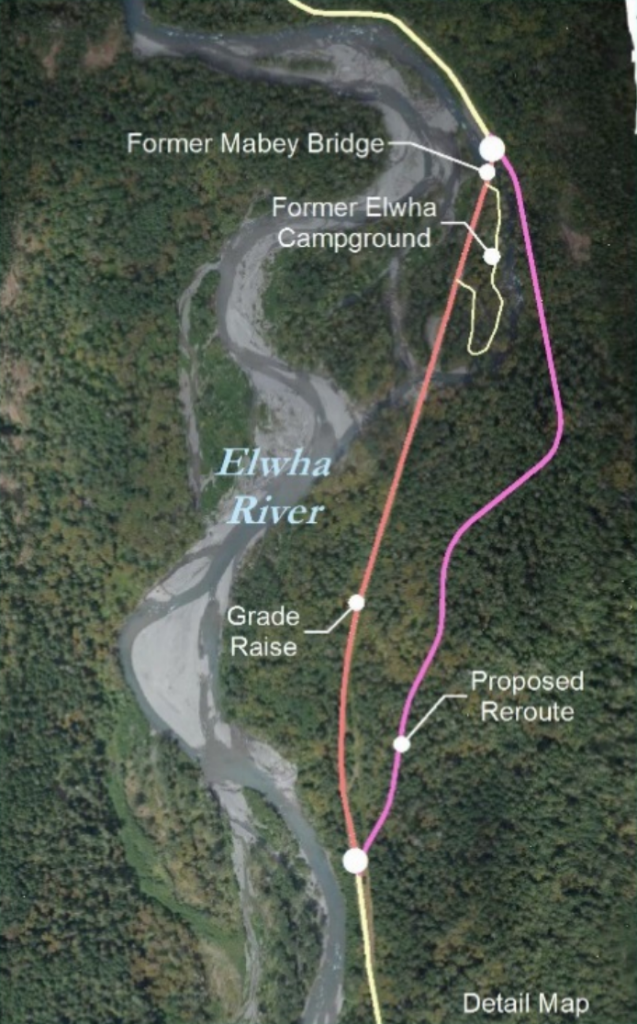

To prepare for this potential scenario, the park proposed raising a section of the road. However, this was a recommended, not a required mitigation measure. Penny Wagner explains, “The USACE [(United States Army Corps of Engineers)] proposed raising the road as a recommended mitigation measure in case the river were to rise from sedimentation from the draining of Lake Mills [(the reservoir created by Glines Canyon Dam)], and storms increased in either intensity or frequency. However, it was unclear whether the road would be washed out, especially to the extent that it was, and that the river would reoccupy its former oxbow once it was free to follow its natural migration patterns.” As a result of this unpredictability, the park did not raise the road. Even if it had, the road would have limited the river’s migration across its floodplain, and raising it would not have been enough to prevent flood damage.

Is There Another Way?

Now, Olympic National Park is proposing a one mile upland reroute of Olympic Hot Springs Road. This would direct the road out of the floodplain and prevent future washouts. Penny Wagner told us they are “currently working on consultation (tribal consultation, State Historic Preservation Office, and US Fish and Wildlife Service).” The construction would begin next Spring, at earliest.

Changing Ecosystems, Changing Infrastructure?

Olympic Hot Springs Road was not built with future dam removals in mind. To me, that’s understandable. But building a road so close to a river is less so. It leaves little room for the river to change. And rivers change—even more so when humans dam and un-dam them.

Ecosystems in general change independent of humans. As a result of humans, the rate at which they change is increasing. These changes are difficult to predict. But we must build infrastructure that can adapt to ecosystem changes, even if we don’t know precisely what those changes will be. This has always been true. But, as we face the ever more existential threats of climate change and extreme weather events, it’s a truth we can no longer ignore.