Detroit Fairgrounds Site: Alternatives to Permanent, Monumentally Bad Decisions

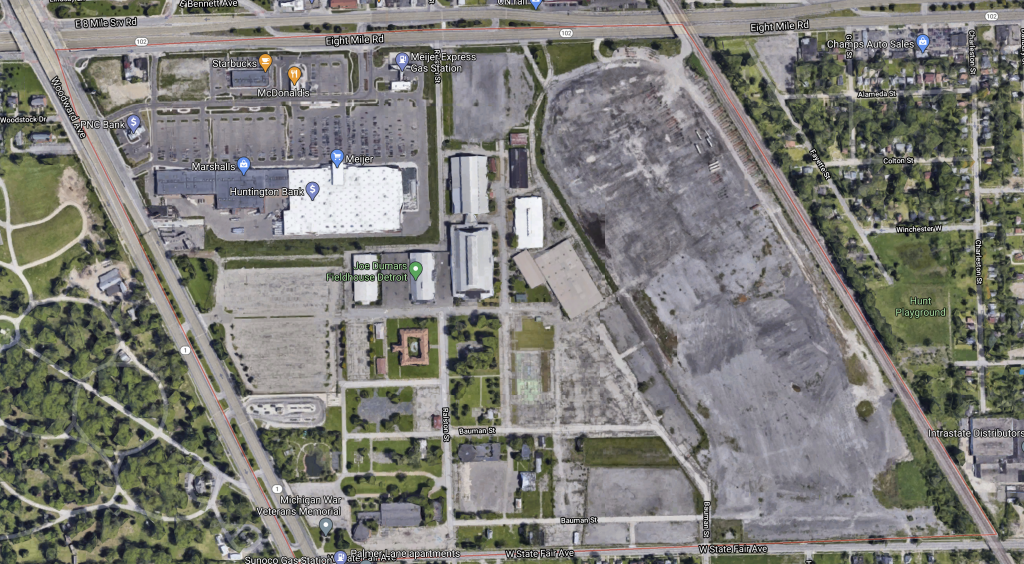

I enjoyed the opportunity to tour Detroit’s state fairgrounds site, which sits at the extreme northern frontier of the city’s border with Ferndale, on the eastern edge of the Woodward corridor. I had gotten the invite from Francis Grunow, and connected with new and old friends and colleagues. Frenemies, in some cases, perhaps. At issue was the question of the redevelopment of the site, which has sat relatively vacant since 2009, when the state fair itself was discontinued– and later revived, but this time in distant, exurban Novi.

OK, SO, WE NEED A TRANSIT CENTER … BUT

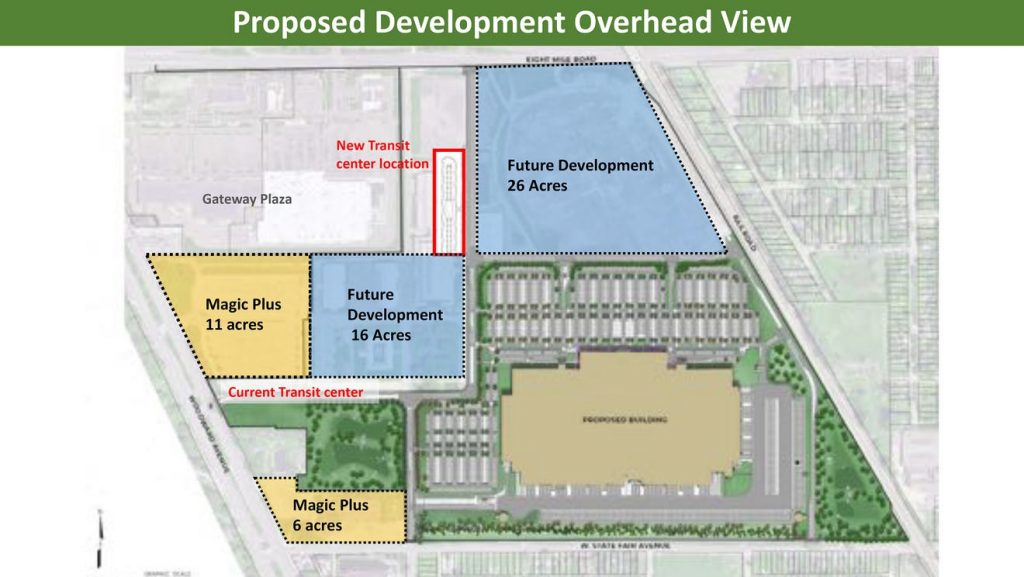

The argument in favor of relocating the transit center, however, is where things get a bit more murky. The city’s position is, misleadingly, that the east-west 8 Mile route accounts for a large portion of traffic in and out of the current transit center. Their argument, that buses must currently make an awkward series of U-turns and “Michigan Lefts,” to get in and out of the current hub, is more or less true. But it is also a bit misleading. The transit hub serves DDOT buses, but it also connects with SMART buses, which serve the suburbs. Painting the transit hub issue as one of interest purely to Detroiters ignores the massive commuter exchange that happens across municipal boundaries with SMART.

For the uninitiated, our suburban buses generally stop at the Detroit city limits and vice versa for DDOT buses. This is largely a product of L. Brooks Patterson, who was awful, is now dead, and was replaced by a progressive, pro-transit Democrat who will probably win reëlection. SMART buses take commuters the whole way downtown and the whole way up to Pontiac, Troy, and any number of stops along the way, covering Michigan’s most urbanized corridor of Woodward Avenue. The wholly inconsistent connectivity between SMART and DDOT is a huge hindrance to comprehensive mobility in the region. Ignoring it in the context of the Fairgrounds project is not only disingenuous, it’s also unproductive and inefficient.

This is a long way of saying that the city is blowing off the Woodward Corridor so Duggan can stick a feather in his cap by building some big building. It’s unimaginative, but it’s also wasteful. A few points why are below.

EXPEDIENCY VS. EFFICIENCY

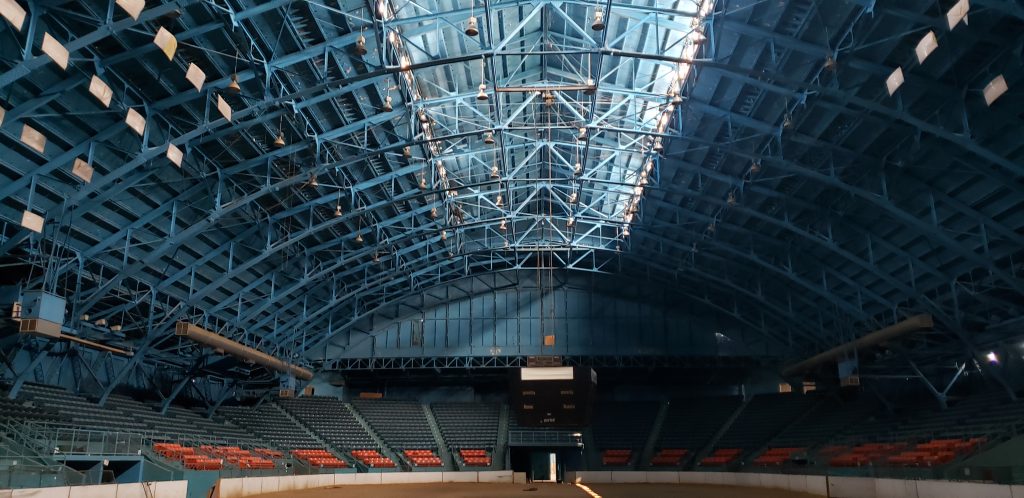

The mayor’s office portrayed the issue as an open-and-shut case. Given the need to relocate the transit center, the city argued, this would put the new transit center right where the Hertel Coliseum is located. The building, they said, would therefore have to be demolished to make room for the new transit center. This is based on a combination of truths, exaggerations, and an ultimately quite strange set of conclusions.

One fact is clear as day: The transit “center” currently on Woodward is indeed, well, not a transit center. It’s a cluster of bus shelters. There are no signs announcing arrivals or departures, because realtime data like that is something we don’t have in a state whose official animal is the F250 Super Duty. There is no signage, really, other than numbers indicating which route stops where. Polcyn pointed out that the current arrangement of raised concrete islands means that bus riders have to cross in front of buses, which can be dangerous. So much is very true. So, no contest, we need some sort of point of connectivity that does not involve a cluster of bus shelters. It’d be nice to have modern ones, where riders can see which buses are coming and when. You know, like real cities have. Maybe public restrooms. Perhaps even fast food, or a ticket office. Hell, maybe even throw a MetroPCS in there!

Here are some other points about the proposed redevelopment.

1. AMAZON WON’T SAVE US

No. I mean, really. Amazon’s current market capitalization, as I write this, is $1.59 trillion. Its stock is trading based on a valuation multiple that represents well over a century of its present annual earnings. That means that investors are betting big on it. Like, generations-long big. But Amazon’s retail business doesn’t really make much money. The company has poured vast resources into building out logistics as a way to streamline delivery services. Indeed, while it has improved its own ability to deliver things faster and more efficiently, this hasn’t translated to a universally improved bottom line. It has, however, grown revenues. The company operates on a basis of what we business nerds call “cost leadership,” which means “selling things cheaper than the next guy in order to increase market share.” This is legal, though Amazon’s aggressive practices have led to questions about their being, indeed, illegally anticompetitive under various commerce and antitrust laws.

Beyond that, critics point out that the company has a dysfunctional corporate culture and a legacy of workers’ rights abuses at its warehouses, where all of the magic happens for its retail business (as far as revenue generation is concerned). Amazon claims to have improved working conditions. But a recent investigation by Debbie Dingell (D, MI-12) and Rashida Tlaib (D, MI-13) found that, well, this isn’t really entirely the case. The two lawmakers were confronted by police as they tried to enter Amazon’s facility near the Detroit airport, ostensibly, Tlaib claimed, so Amazon could do some cursory cleanup before their tour. Doesn’t really seem to bode well. But those prices!

Duggan has a magpie-esque affinity for shiny things. It isn’t new. He’s thrown literally billions at Dan Gilbert. Billions at the Morouns and the Ilitches. What do all of these entities have in common? They’re multibillion dollar enterprises. The city is not any better off as a result. Or, if it is, it’s still losing population and still heavily dependent upon casino revenue. So, yes, let’s just leave it at this: WE NEED TO STOP RELYING ON SILVER BULLET SOLUTIONS. IT’S 2020.

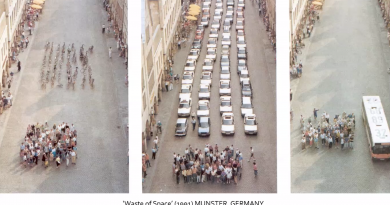

2. SPRAWL WON’T SAVE US

There’s a widely held belief among terrible municipal bureaucrats that if we can just emulate the suburbs in the inner city, we’ll succeed. There are numerous examples of this around Detroit. The Detroit Housing Commission’s Gardenview Estates, for example, on Joy Rd. Culs-de-sac, pristine lawns, and automotive dependency. Or Hartford Village, a Premier Senior Living Gated Community, conveniently located right in the middle of the hood! I mean, do city planners really think this is what’s going to save the city? Clearly, if we keep doing it. The Gateway project– at 8 Mile and Woodward, just north of the Fairgrounds site and previously carved out of it- is a good example, too. While that project is arguably successful, the question is how much more successful it might have been if it were built denser.

3. A DENSER, MORE SUSTAINABLE BUILT ENVIRONMENT IS OUR BEST BET

An investment consortium that included the legendary Magic Johnson— probably primarily for name recognition plus some hefty equity contribution- appears to have amounted to naught.

But look. The Fairgrounds site is huge. It’s huge enough that it’d be possible to build dense stuff, build more dense stuff, preserve the existing buildings, and still have green space leftover. There’s no reason why Woodward, for example, can’t have five story buildings fronting on it. Hell, there’s no good reason why Eight Mile can’t, either. But in the mean time, we’ve got a huge site and some huge, already-built buildings on it. There is no way that it’d be cheaper to demolish these buildings at a seven or eight figure price tag, build new ones, and then think we can get a good value for redevelopment. That just isn’t a thing, Luke, come on!

Fortunately for anyone thinking about the climate for development, though, we have a lively CDFI scene. We have banks interested in lending. We also have private investment capital ready to go. What we lack in the case of development for the Detroit fairgrounds site is vision. That vision cannot come from technocrats with Ivy League JDs and MBAs, but, rather, from community leaders, boots-on-the-ground entrepreneurship, and, hopefully, some folks who have an interest in building a sustainable future for the city.

More updates coming as I get them.