Indoor Air Quality and COVID

Green building is increasingly focusing less on hi-tech lightbulbs alone and more on a holistic building that is not only energy-efficient but also healthy for occupants. This comes up in my participation with the Michigan Public Service Commission’s Energy Waste Reduction statewide workgroup. It is also something that is becoming more topical amid the novel coronavirus pandemic. What is the role of building science in protecting us from sickness? How do we beat COVID while also improving indoor air quality?

THE BUILDING’S ROLE IN HEALTH

The building’s primary role in this regard is to passively protect occupant health. This means things like zero-VOC finishes, nontoxic construction materials, and an envelope that keeps occupants sufficiently warm in the winter and cool in the summer. This isn’t rocket science, and it’s increasingly the norm as mainstream retailers adopt predominantly zero-VOC finishes. (Basically any product made with a petroleum distillate base that exudes a foul aroma after being applied is emitting VOC’s). Having used a few all-natural, zero-VOC products, I can attest to the fact that there are reasons why we use toxic chemicals. But I’ve been trying to move well the heck away from the toxic stuff in recent years for reasons of protecting, uh, Gaia, and our bodies.

A secondary role– which is certainly up for debate to some degree- is the question of the building’s active role. While, as one Philadelphia architect once opined to me, “good architects have been building green for thousands of years,” active systems in buildings are really a relatively recent phenomenon– think past sixty years-ish. The prevalence of forced air was made possible through the widespread availability of cheap motors, sheet metal, and people who knew how to install them. Postwar suburban boom, anyone? Since this time, forced-air has become the norm. Beyond this fairly minimal modicum of home activity, automated by a simple thermostat, we’ve now got things like “smart home” technology. The Internet of Things. Sergey Brin and Jeff Bezos are locked eternally in a duel inside your subconsciousness as your Alexa and your Google Home debate with each other.

In the age of the ‘rona, we take extra precautions to sanitize surfaces– and air. Forced air’s popularity is largely because air is the medium through which we experience conditioned space. In other words, if we enter a space, we are less likely to notice if the walls are cold or if the floor is cold. Rather, we notice if the air is cold. This is a good starting point for thinking about COVID-related protections, because it suggests that while you should probably sanitize a surface if you sneeze all over it, the biggest issue is the airflow question.

So, uh, how do you clean inside air? Air filters are a simple option. Every forced-air system has one or multiple air filters, typically installed at an air return or at the return plenum of the furnace itself.

CONDITIONING AIR WITH ULTRAVIOLET LIGHT

Ultraviolet light is another option. Sorry, Trump, there is no way to inject that light into your body. But an easy solution is to stick a UV lightbulb into an air handler. Such technology isn’t new– we’ve had UV lights for a long-time- but it’s mostly been limited to scientific and healthcare venues.

In a residential forced-air unit, the system is quite simple, requiring a regular power supply (i.e. outlet). Amazon is selling a few– one for $149.99 and a Honeywell model for $184.49. Bulbs are relatively cheap and supposedly have a lifespan of several thousand hours or more. Most designs seem to involve cutting a hole into the furnace’s plenum and sticking the bulb through it so it can irradiate this air. Don’t worry– that’s not ionizing gamma radiation, it’s UVA/UVB that is absorbed before it gets pushed into the house. There are some health concerns, but they mostly involve, uh, not basking in the glow of the light– and making sure it is not emitting wavelengths that provide ozone.

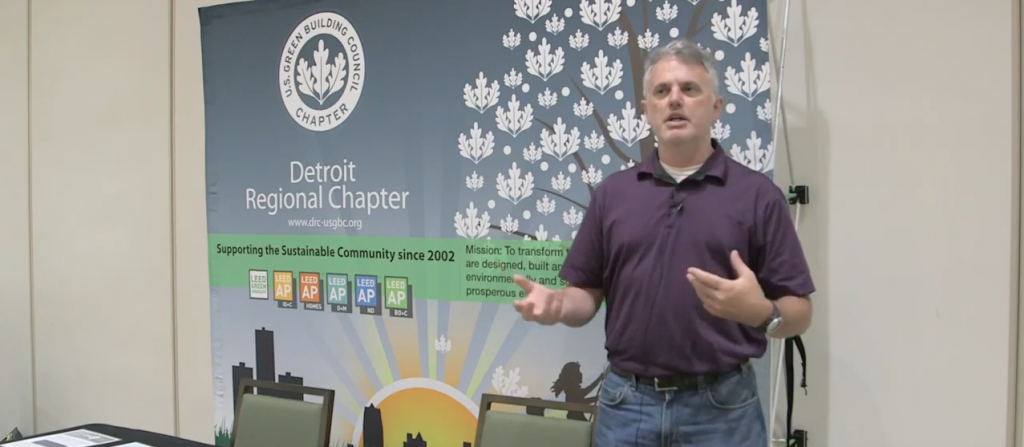

But Kevin McNeely, a veteran of the building performance sector and longtime Handbuilt co-conspirator, tells us that while these might work to improve air quality, he hasn’t seen any body of research that suggests that this is necessarily a precaution against COVID.

OTHER FUNCTIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

“You’ve got some questions you have to answer: It’s airborne, but for how long? And is [the virus] gonna stay airborne long enough for your air handler to move it past a UV light? How long does it have to be exposed to the UV light? How powerful is that light? Is the air moving past that UV light faster than the UV light can kill the virus?”

McNeely, who is currently providing performance testing for a number of planned, under construction, and finished construction projects around the Midwest, says he suspects that there’s a bigger issue with surface contamination than with untreated airflow. He mentions that when he’s had to travel for work in recent months, hotels will have an assiduous sanitizing regimen that is apparent– and duly communicated- to guests. (No COVID yet!).

Also, forced air systems are, he points out, not typically designed to be pulling air equally from every room in the house. In other words, you can’t possibly expect to have a UV-treated system that will protect, say, attendees of a house party including someone who is potentially COVID-positive. The UV light would be an added benefit, but not a protection from COVID.

“It’s kind of a best practices thing,” he explains. “Like, okay, great, you have this UV light. But are you sanitizing household surfaces? Is your air conditioning unit properly sized? If we can’t trust homeowners to change their air filters [on the prescribed maintenance intervals], can we reasonably expect them to maintain best practices for cleaning surfaces?”

TAKEAWAYS

McNeely concludes that a UV disinfectant system isn’t going to hurt anyone– if installed and used correctly. (I keep thinking that UV isn’t a bad idea after attending a presentation in 2018 where a gentleman claimed that about two thirds of all commercial chiller units have detectable amounts of legionella DNA on them). But he emphasizes that it’s more important to understand the building as an entire system. Change your air filters on a regular basis. If you’re getting a new HVAC system installed, make sure it’s sized correctly. No forced-air? You can always consider single-room systems. But open your pocketbook, because they ain’t cheap.

In the mean time, wear the damn mask. and wash your hands, people. And let us know if you have any experience with these systems!

Handbuilt receives a commission if you buy a bunch of the air filters we’ve linked to, or UV lights. So, you know, buy them. Acutally, don’t. Buy them from a local retailer, not Jeff Bezos. And hire Kevin to do LEED or HERS consulting.