How Losers Still Get Paid: Why Bankruptcy Can’t Rein In Executive Compensation

IF YOU’RE ONE OF THE BILLIONS OF ONLOOKERS OBSERVING THE COLLAPSE OF THE GLOBAL ECONOMY, you might be wondering: what’s the deal with all of these rich people getting paid while normal people are struggling and losing jobs? The simplistic, critical characterization is that liberal capitalism is fundamentally evil in every way and that’s just the way the damn cookie crumbles. Better spray-paint a federal building, I guess! Perhaps the most dangerous characterization is that, “well, those rich people worked hard, so they deserve to get paid, even if their companies fail.” The first characterization is lazy and incomplete. The second characterization is demonstrably false. Neither of them get at the root problem of why this system continues, unchallenged by policymakers or other stakeholders. Why is such lavish executive compensation still possible, even when companies are facing bankruptcy?

This article lays out a few ideas.

FIRST: FIDUCIARY DUTY TO ‘WHOMST’?

(You heard me). The question at hand is to whom the firm has a fiduciary responsibility? Is a company obligated to make money? Is its sole purpose to turn a profit? To either one, yes. But beyond that most vague definition, the details get fuzzy.

- Agency theory: One assumes that staff working in the company’s best interest. But implicit in this theory, considering the complex evolution of the corporation, is the principal-agent problem. The firm’s workers want to keep getting paid. In order to do this, they must continue to deliver value to the company. The executive management wants to get paid, too. Ostensibly they do this by delivering value to shareholders. Unfortunately, though, usually they also are shareholders and are often rewarded with stock bonuses and options. This presents a conflict.

- The shareholder value, or shareholder primacy model, says that companies are obligated to maximize return to their shareholders. Conflict between maximizing short-term return to shareholders (and therefore the executive) usually conflicts with long-term strategy for profitability. An increasing number of academics and business folk, like Lynn Stout, argue that the idea of maximizing shareholder value is essentially bullshit. There are a few ways to look at this question. Shareholders buy stock in the first place to raise money for the company. They’re entitled to voting rights and some sort of upside of their investment, hopefully how much money the business earns in the future. This is paid out sometimes in a cash dividend. Sometimes it’s not paid out but rather the company delivers that return in the form of appreciation. Increasingly, companies are stockpiling cash and not paying out dividends. Companies also use a lot of their cash– plus things like the Trump tax cuts- to buy back stock. This raises the value of the stock. More market capitalization means more money for investors. It also means more money for executives (See next section).

These Wharton Types will argue that it’s necessary to pay executives that much, because it’s necessary to attract talent. That’s what the market will bear! Where did you get your degree, American University? CEO’s gotta get paid $30 million, or they won’t be good CEO’s! Nice! But it’s, uh, completely not true.

SECOND: FAILURE TO MITIGATE THE GREED INCENTIVE

Developed economies have seen increasingly limited growth potential in the past few decades. Slowing population growth rate and an increasing skepticism of globalization and immigration mean that markets are fundamentally limited by the number of potential new consumers. Since 2009, we’ve financed most of our economic growth through debt. We’ve also allowed policymakers and Those Wharton Types to successfully argue in favor of (widely disproven) Reaganomic theories, facilitating this upward transfer in wealth. Wealth disparity makes for an inefficient economy. It limits growth, competition, and innovation. Trickle-down, like fetch, isn’t a thing.

But combine this problem with the first issue mentioned above. You’ve now got executives who have no disincentive to make way the hell more money than they’re making now. To be clear, there is no “best” approach to compensation in management theory. There is a lot of agreement that compensating people based on performance is generally good. There’s a lot of agreement that making people feel as though they are fairly treated and fairly paid generally produces good outcomes. There’s also a lot of agreement that paying executives millions doesn’t actually improve the company’s bottom line at all. Boards argue that “but we have to pay them in order to keep them here, they’re doing such a good job.” This is what we might call a “major ‘bruh’ moment.” These executives either shepherded your company straight into the gates of bankruptcy or failed to prevent it from getting there. Get out of here.

THE LIST

Let’s look at the folks who didn’t get the memo. Who were the losers of this round? How much are their executives getting paid? We’ve got a good sampling of the continued retail apocalypse as well as victims of the recent oil crash. 2018 saw Sears (which could get its own crazy book written about how an executive was somehow permitted to turn a vaguely functional company into a conflagration and then buy back the ashes at a discount), and Bon-Ton (good riddance, frankly). 2019 saw Forever 21 (private), Dean Foods (OTCPK: DFODQ), Pacific Gas and Electric Company (NYSE: PCG), and Payless (owned since 2012 by private equity as well as Michigan-based Wolverine World-Wide, the collective of which carved up the company and saddled with debt). Are you seeing a trend here? Managers and execs get paid and companies go bankrupt? Hint: It ain’t just the retail apocalypse.

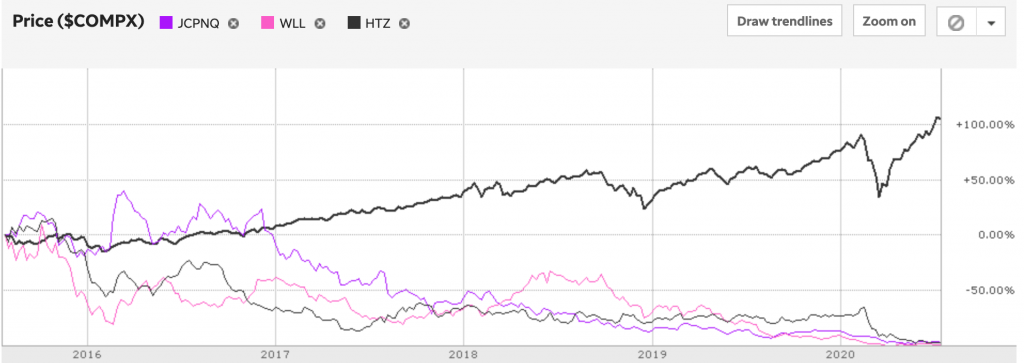

JC PENNEY (OTCMKTS: JCPNQ)

How the mighty have fallen. JC Penney, a centenarian-plus staple of American household consumerism, furloughed 78,000 employees. But also paid $10 million in executive bonuses. I had an union-made Stafford suit from JC Penney that lasted several times longer than the current tenure of CEO Jill Soltau. Not cute, Jill! JCP Has lost 99.66% of its market capitalization since 2007, and 97.58% since 2016 alone.

NEIMAN MARCUS (PRIVATE)

Ten million dollars to executives pre-bankruptcy. The retailer, which has been kicked around from private equity owner to owner in the years since Stanley Marcus died in 2003, delivered $3.6 billion in revenue in 2019. This was down from $4.9 billion in 2018. It’s owned jointly by a private equity firm and by the Canada Pension Plan. Observers might note that the pillaging of the company by private equity is a common thread. The company’s debt doubled in ten years to over $5 billion today. Its previous owners, however, made bank off the sale. Private equity is notorious for buying a company with respectable cash flow and using that cash flow to borrow massive amounts of money in order to get rich off the company, while then using the debt as an excuse to slice and dice operational expenditures– like jobs.

WHITING PETROLEUM (NYSE: WLL)

Not to be confused with Whiting, Indiana (of refinery fame). Whiting Petroleum corp is a oil and gas exploration company based in Colorado. The company doled out a cool $14.6 million to executives just days before declaring bankruptcy. WLL has lost 99.7% of its market capitalization since its peak in August 2014.

CHESAPEAKE ENERGY (OTCPK:CHKAQ)

The Oklahoma-based fracking giant features prominently on one of those Hall of Shame lists of the top polluters in the world. It has lost more than 99% of its capitalization since 2015. Looking at examples like the decline of the US automotive and steel industries in the latter half of the 20th century, it’s easy to blame macroeconomic conditions for your company’s failures. But Chesapeake was struggling well before COVID-related oil price collapses. More like “Marcellus Fail,” am I right? (I’m sorry– I’ll collect my things). The other problem with the shareholder value model? When times are good, they’re good. This is often based on quarterly determinations. But when the shit hits the fan, shareholders often receive no protection. This article points out that shareholders of CHK stock are effectively now holding a worthless asset. What was once several billion dollars in equity is now, well, potentially worth nothing.

HERTZ (NYSE: HTZ)

America’s favorite black-and-yellow car rental brand first started as a company renting out Models T over a century ago. The owners sold the company to General Motors, which owned it from 1926-1953, when John Hertz repurchased it. The company would later be sold to RCA (1967), then to United Airlines (1985), then Ford (1987-2005). Private equity bought it– and later took it public. A hefty public subsidy package from the state of Florida drew it from the Dirty Jerzz to the Sunshine State in 2012. The stock has lost 98.6% of its peak value in 2014. Hertz paid out more than $16 million in executive bonuses before declaring bankruptcy.

LEGAL REMEDIES

A policy revolution is unlikely to be led by a White House whose occupant spends more time tweeting in all caps than governing. Shareholder lawsuits are one option. A class action suit could argue that the firms breached their fiduciary duty to shareholders by doling out tens of millions of dollars in executive compensation while knowing that the firm was in financial freefall. Such a lawsuit could also hold board members personally liable (In re Caremark International Inc. Derivative Litigation, 698 A.2d 959 (Del. Ch. 1996)).

Shareholder lawsuits are common– but often fail to right these wrongs. Bankruptcy does not shield management from liability. It shields the company from debt. But most shares are wrapped up in passive ownership, that is, Joe or Sally hold investments in retirement, and the retirement fund invests their money into these companies. The individual has a limited amount of agency. This can change, but it will require individuals to consciously decide to manage their own money. As we’ve seen a resurgence of FOMO investing from retail investors amid the current bubble, it’s also worth noting that this probably won’t end well.

POLICY REMEDIES

Another option is to reform the tax code and reduce the incentive for companies to lavishly compensate executives at the expense of shareholders. While we’ve seen trillions in wealth transferred skyward under mostly Republican presidential administrations, the Democrats have done little to mitigate it. That may change in November, as virtually every poll has voters begrudgingly favoring former VP Biden. Lower-hanging fruits are also worth looking at through reforming securities regulation. It’s an unsexy approach, sure. But measures that would balance more stringent impositions onto giant companies could be balanced accordingly with incentives for smaller companies. Other easy targets would be attaching strings to incentive packages or tax breaks to curtail executive compensation in the case of corporate bankruptcy. Limits on private equity’s nefarious financial sorcery, management fees, and dividend recapitalizations would also be a good thing, because it might save a few companies from bankruptcy in the first place.

Regulation is debatable, though near-term feasibilities are anyone’s guess. What is pretty certain in the mean time is that these companies aren’t recovering any time soon. And the only people who have won here are, well, the bosses.