If You Don’t Build It, They Won’t Come: Development & Gary’s Stadium

NWITimes’ Keith Benman recently wrote two articles highlighting the failure of the US Steel Steel Yard, Gary’s minor league baseball stadium where its own Railcats play, to spur economic development along the US-12/20 corridor. Is all lost? Hardly.

The Railcats stadium was built more than ten years ago at a curiously high cost– almost $50 million in comparison to comparable stadiums built at half the cost. Benman reports that a lot of the skepticism surrounding the figures, especially by then mayor hopeful (now Mayor) Karen Freeman-Wilson, suggested that the $50 million worked out to some substantial political payouts. Impressively, though, the last cent on bond debt of $45 million was paid off more than two years ago. (In comparison, St. Louis’ Edward Jones Dome will be paid off by 2021, by which time the Rams may be six years gone from the city and the total cost will be an estimated $720 million.)

Let’s look at everything that’s innately pretty great about the stadium, first off, which is a huge incentive for Hoosiers to not have to travel all the way to Chicago to see the Sox play: Tickets are a bargain at $9 for the most expensive seats (buy one get one Tuesdays and $1 for your second ticket Wednesdays, so, effectively $4.50 and $5.00 tickets) compared to the Sox’ up to $77.45 for those same seats. Back of the back row will run you just over $9—but it’ll take you an extra few hours to make the hike up there, so the savings are a wash. If you ever happened to suffer a major life crisis or, for some other reason, wanted to see the Cubs, you could for a similar price range of $20-120. (Doesn’t the staggering number of foul balls alone make minor league way more interesting?)

The cash-only concessions boast $5.75 beer (25% discount to the Sox, for example) and a wide variety of food, although I was a bit disappointed that I could not find a baseball helmet filled with nachos. Parking is free. So, it’s not surprising that the stadium is a profitable local hit– its largest fan base actually drives all the way from Valparaiso, a city about half the population of Gary and half an hour away, probably comprising folks who didn’t want to negotiate the hassle or cost of seeing a Chicago team.

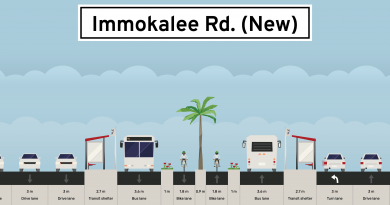

But yet, Benman notes, the stadium appears to be failing to act as a catalyst. Never mind that US-12/20 have been under construction for a year and are just now being completed with new asphalt, across various intervals over the past year making the passage through downtown Gary in an automobile unusually treacherous. Road work, and it can only be called that, as it didn’t exactly include separated bike lanes or a BRT lane, doesn’t work wonders for improving the accessibility of a street. Of course, that doesn’t excuse the previous eight or nine years, but there was also a pretty hefty economic downturn that didn’t do much to help the district.

In considering whether a project actually improves a city or not, revitalization must be measured on a human scale– of neighborhoods and walkability. This is one of many reasons behind the failure of urban renewal efforts in the 1960’s and 1970’s, which advocated “slum clearance” in favor of Corbuserian, monolithic complexes with single owners and operators, occupying massive amounts of space and separated by a chasm from any human scale.

Economic development, still often thought of by planning officials as a matter of what will have the best return on paper through a multi-million dollar city investment, is as much spatial as it is about money or productivity. In the case of downtown Gary, the vast majority of space is occupied by parking lots, and the few large buildings left either have owners who can’t figure out what to do with them or are in such disrepair that there’s simply an insufficient supply of money to support their renovation into something better.

Still, the key in developing this strip is figuring out how to solve the problem of the complex and absentee landownership which plagues Gary, as it does many cities with high rates of abandonment. Negotiating development prospects with the owner of an even vaguely habitable building is not for the faint of heart, since most of those building owners want something in between mitigating their liability and selling the whole thing and being done with it. In cases where the ownership structure is so abstract, complex, or fundamentally dubious– seven heirs in Puerto Rico plus an additional dozen liens was the best I’ve come up with, or perhaps one parcel of vacant land in Miller that was owned by 31 people- that the only way it can be transferred is essentially through public expropriation.

This could work in the case of the dozen or so larger buildings in this immediate part of the downtown that are vacant and centrally located. But expropriation by the city won’t help if much of that land remains undeveloped– and namely parking for the stadium and municipal buildings. Promoting higher-density development against those two interests would be a tough sell.

Concluding on a positive note, there are some signs of life in downtown Gary– Benman notes the Steel City Grill and Fresh Coast Coffee, two new businesses along this strip. These small, individual and family-owned establishments replace a Bennigan’s restaurant formerly housed in the Stadium, which, in addition to its parent company going bankrupt, was also plagued by some major criminal activities. It’s no (St. Louis Cardinals) Ballpark Village, but two new businesses within walking distance is a start. There’s also the fortunate reality that empty space can (and should) be made and remade in inner cities, and there’s plenty to go around.

(Portions of this article were submitted in an August 11 letter to the editor of the NWI Times.)