When Is A Building A High-Rise?

No, this is not a silly riddle with a dad joke punchline, it’s a genuine question– and one that comes up a lot in popular discourse about urbanism, architecture, and housing, but also in professional discourse about these things. Why? Because we don’t have a simple answer, in most cases. TLDR: it depends on the jurisdiction and what code they use– and, of course, because municipal bureaucracy with respect to buildings can never be simple, it also depends on local code amendments. Miraculously, zoning is only minimally implicated here. Let’s dive in!

A High-Rise, From A Code Standpoint

IBC and NFPA define a high-rise as a building with an occupied floor more than 75 feet above the lowest level of fire department vehicle access. Some provisions in IBC refer to an “occupied roof,” and certain local codes have their own alternatives that might be close enough (80′). What is an occupied floor? Generally something that is usable for productive purposes. A mechanical room that is not consistently staffed with human beings does not count as “occupied.”

One common complaint about codes– which I covered in a 2024 article about the push for fire code reform– is that they are often written with an assumption, either explicit or implicit, that virtually any building that is not a single-family house is a commercial building. This is one of the things we’re interested in working to clarify through our work with Abundant Housing Michigan (as we just hired our first executive director this week!).

The adage that “any non-SFD building is commercial” not unequivocally true, but it’s functionally true enough because the IRC covers only detached one-family and two-family buildings plus townhouses three stories or fewer, and a very short list of exceptions to what would push a builder into the IBC, which governs commercial codes. Is it silly? Yes. Is it intentionally designed to bad and confusing? Probably not, but ask the fire safety engineer quoted in my single-stair reform article (below) what he thinks.

Is it completely divorced from construction reality in a way that undermines the rate at which good quality housing in good quality urban fabric can be produced? Absolutely.

A High-Rise, From An Engineering Standpoint

As a building gets taller, the technical requirements of its design and operations become increasingly intensive. In the average wealthy western economy, for example, pressurized municipal water distribution systems allow for buildings to be built several stories high before the building requires supplemental water pressurization– contrast with parts of the world with limited water pressure or less well-developed municipal water distribution, where buildings might require water storage in cisterns or tanks to compensate for limited water pressure. A tall building always needs supplemental pressurization, and the systems to manage this are well-understood.

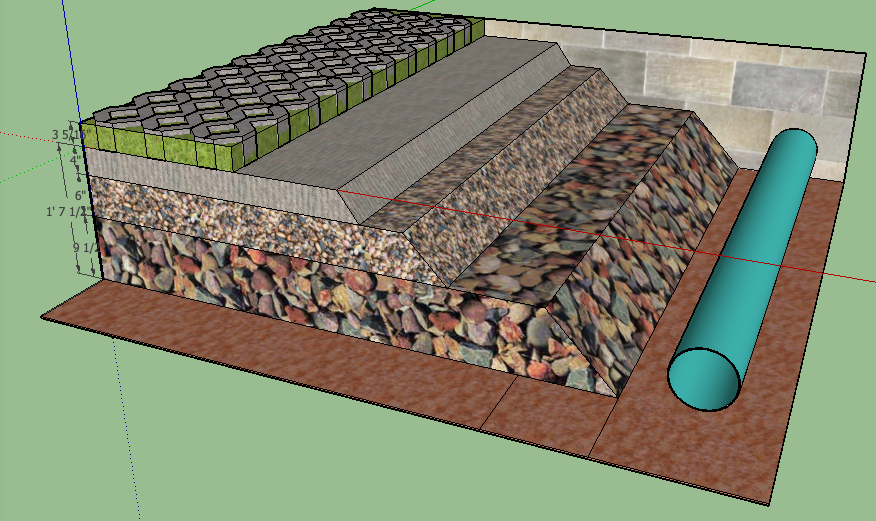

Design while thinking about height also requires attention to construction materials and methods. Masonry buildings in the United States historically rarely exceeded four stories, if you think about buildings like the historic New York City brownstones, while stick-framed structures were usually limited at a similar height. Modern construction methods allow for 4-5 stories with wood, especially with hybridized podium buildings (very much commercial construction).

The maximum buildable height from an engineering standpoint is tricky because the IBC has tightly defined parameters dealing with maximum distance between interior spaces and emergency egress pathways that must also be paired with an exhaustive (and frankly quite confusing) set of rules around construction materials balanced with space use-type. Podium buildings, for example, in which a steel and concrete can have a multi-story wood-framed structure built on top, effectively treats above and below that podium as completely separate from a fire separation standpoint. A stick-framed, assembly-rated room is treated completely differently under IBC from a steel-framed storage area, for example, and it has to do with not just construction materials, but with what will be going on in that space as a matter of emergency safety.

Is it safe? Structurally, yes. Fire-wise? Also yes! IBC has strict parameters around not only emergency egress or fire ratings, but also things like accessible spaces where one can shelter in a fire or other emergency event, or, of course, sprinklers.

Why not zoning?

I often ask my students why they think we don’t have a model zoning code if we have a model building code. They don’t have a good answer for it, and neither do I. On this topic more than most others, zoning in most jurisdictions seems to defer to the IBC’s definition of a 75′ height limit as where “high-rise” begins.

Zoning codes are often agnostic to how tall a building is beyond a certain point because it focuses more on things like floor-area-ratio, or setbacks that make certain heights geometrically impossible. This was a driver of architectural character in New York City for a large portion of the 20th century as Manhattan densified to the point that planners recognized the need for designs that would allow natural light. This has changed substantially with the advent of things like glass curtain walls and envelopes that are mostly glass, but the legacy remains in the form of a lot of older buildings built to the city’s historic setback rules from 1916.

Until we get a zoning code that is harmonized with an IBC– and an IBC that itself is, we hope, eventually going to be modernized to allow for clearer interpretation about how to build smaller commercial or multi-family residential buildings- we’ll have to settle for trying to understand an individualized approach to building anything across the confusing patchwork of regulatory jurisdictions in North America.

Conclusions?

A 75′ building (22.86m) or taller is effectively considered a high-rise under IBC and IRC. But this, of course, isn’t the whole truth. IBC and IRC, despite having “international” in the name, are only really used in the United States. This means that these lessons will not hold up across international borders. Canada’s NBC seems to demur, with a 59′ (18m) height for this tall building category, which is close to the same standard in the UK. Germany’s number is closer to the US at 22m before a Haus becomes a Hochhaus (high house, or, tall house).

Other countries have completely different numbers including Mexico, Spain, the Netherlands, and France, which all seem to have a higher definition of where “high-rise” begins. A lot of this is a product of different construction methodologies. We use stick framing in the United States because we’ve been building with it for a long time and we know how to do so in a safe and cost-effective manner. When the average typology is a single-story, two-story, or three-story building built out of block and rebar, that’s a completely different starting point, and it defines how what I’ll call “code culture” deals with these issues.

In the US, we know that these codes are also desperately in need of revisions to allow developers and builders to build denser buildings that are not true “high-rises” in the classic sense– think 4-6 story buildings that might hit that 75′ limit and are fundamentally not the same as building the Sears Tower, but are effectively governed by the same restrictive code. Let’s fix it! We might not all agree on what defines a “tall” building. But we should all figure out a way to agree that we need better ways to more easily build buildings of an intermediate height and density.