The Mom & Pop Stores Are Dead. Long Live The Mom & Pop Stores.

I had a bizarre thing happen this week at work that gave me the opportunity to think a bit more about something that’s always on my mind, and that’s the tilt of this strange nation, to quote Joanna Newsom, toward that whole glorious goal of capital aggrandizement. Bigger is better, they tell me! But bigger also starts off with a huge advantage, right? You often have access to cheaper capital, economies of scale in both things like volume procurement and more efficient operations, and you can usually use that higher volume and cheaper capital to lower prices! How has this gone for the mom and pop hardware stores in recent years?

In some regards, not so well. There are a lot of forces working against independent retailers in this age of mega-agglomeration. In Detroit alone, I’ve seen a few closures of independent hardware stores since I’ve been here. But it’s not all doom-and-gloom, and there are complex reasons for why. The cracks in the foundation of big business are not easily exploited, but they’re worth mentioning.

Hardware Retail Through The Ages

First, it’s hard to estimate how many independent hardware stores there are in the country because there are some blurry definitions. There are hardware stores, which we think of as a place where we can buy everything from screwdrivers to paint. Many of these stores have diversified into things like housewares, consumer electronics, and odds and ends. Local honey? Fudge? Yeti coolers? Why not? Go nuts, guys. (Narrator voice: …and they do).

Indeed, the American General Store has a storied history that goes back to the pluralistic, peaceful, halcyon epoch of Manifest Destiny, when men were men, women were women, and a good cigar was a smoke. We have this thoroughly romantic idea of this down home kind of establishment where there’s a fat cat sleeping in front of a wood stove, or an old man smoking a pipe in a rocking chair– where you buy some tools and some dry goods and they package it up in a thick brown paper bag and send you out on your way (on your horse, or what have you). Prior to the development of “modern” transportation and logistics systems in the 19th century, there wasn’t really such a thing as a centralized retail destination if you were outside a city. That is perhaps a story for another day, but suffice it to say that consolidation of retail establishments seems to have begun as cities began to consolidate. In the 19th century, this followed railroad expansion– the primary method by which people and capital were delivered much more quickly than by equine.

This retail model further changed with the advent of the motorcar. Whereas prior iterations of retail required a horse-drawn cart to load things from a train and then deliver them to the retail establishment, trucks and cars increased the speed with which this was possible. This made it far more affordable to centralize inventory in a single destination as opposed to having more complex calculations for delivery, purchasing, and scheduling of either. While the remaining general stores in the United States– those that haven’t, say, been converted to fancy brunch spots- are really more grocery stores than hardware stores, it’s an interesting note as we trace the evolution of the American mercantile economy.

NAICS vs. Census: A Data Challenge?

Over the past half century, we saw a lot of diversification in the types of retail establishments, to the current setup we have. The classification of a “hardware store” often covers not only places like your local Ace, but also stores that sell, well, home improvement-y stuff.

NAICS, for example, divides this category of retail establishments into “home centers” and “hardware stores.” The biggest distinction here is that the former sells building materials. Of course, anyone who has ever even peeked outside of the Plato’s Cave that is the world of residential construction, knows that Home Depot and Lowes are for residential builders and home improvement aficionados. They’re not, for the most part, where you buy 1000 sheets of drywall and have them delivered with a crane to a fourth story. Such is apparent for anyone who has ever tried to deal with Home Depot to do real work that depends on a real schedule. The customer service is just not there. Warranty problems? Good luck. Scheduling issues? We’re not liable. Damaged materials upon delivery? Get bent, bucko.

My favorite one is when you install a product, have a problem with it, and then try and get in touch with the retailer. What do you expect them to do? Send a technician out? Dispatch a crew from Eau Claire, Wisconsin, to drive to your crib in Detroit? We had this issue with a very expensive thing we bought from Menards. They wanted us to fill out some paper form and fax it to them. Making things like this hard from a standpoint of business processes is an age-old tactic companies use. I’m currently dealing with this saga from Newell-Rubbermaid on a warranty for a work item. They want me to jump through any manner of hoops. I’m going to do it. Mostly because I have a very hard time letting things like this go. I’m also exceptionally good at squeezing solutions out of companies that are used to consumers just rolling over and brushing it off.

Stores like Menards or Home Depot can get away with this because they are big and sell in volume. Volume often, but I wouldn’t even say usually, translates to cheaper prices. Anyone who can brag– or lament, one- having spent six figures on home improvement stores in their lifetime can tell you why they prefer one retailer over another, and it’s never as clear-cut as one being entirely superior. Menards has a far superior selection of tools, especially in the realm of woodworking and carpentry. It’s got a way better selection of fasteners. Home Depot, however, has a perhaps quicker-and-dirtier setup if you want to pop in for ten pounds of drywall screws.

On the other hand, while “Big Box” retailer is fairly straightforward, there’s a bit of a question mark around whether you would count regional, usually privately-owned chains as “Big Box” stores. You’ve heard of Lowe’s and Home Depot, of course. Menards, the third-largest big box home improvement store chain in the country after Lowe’s and Home Depot, operates in fifteen states, almost all in what I might stretch very far to call the Much Greater Midwest (as far west as Wyoming and as far east-southeast as West Virginny). That seems to make it a big box store. Mills Fleet Farm operates 48 stores in five states. Rival Blain’s Farm & Fleet, in comparison, operates 44 stores in four states. There are smaller ones, too!

For NAICS purposes, these are classified mostly as “home centers.” There are other codes to cover things like paint and wallpaper stores. There still fuzziness: “Other Building Material Dealers.” What other materials? Many stores, as mentioned before, and going back to Ye Olde General Store model, will sell multiple things, too– similar to how a company will advertise that it is in the business of plumbing and heating. Another coding covers “building material and garden equipment and supplies dealers” among many other categories. Complicating things further is one of the most popular hardware stores, Ace, which is a national “retail co-operative,” comprises locally-owned stores that buy common brands from a centralized distributor. It’s basically the same model as a franchise restaurant.

Census data show a decline in the number of independent hardware stores over time. But it’s not a crazy decline– nearly half of American hardware stores in 1992 were classified as independent, while that number had only declined a few percentage points– from 47% to 42%- by 2018. COVID kinda derailed our numbers. A report from IBISWorld published in 2020 noted that the hardware retail industry in the United States had declined at an average annual rate of 0.3% over the five years to 2020. This decline was attributed in part to competition from large home improvement chains and online retailers.

But with the slowing of stonks (Home Depot, for example, increased its market capitalization fivefold over the past decade-ish), and with Amazon’s growth rate slowing substantially (irrespective of economic growth slowing down at large), it seems perhaps safe to say that rumors of the death of the mom-and-pop hardware store have been greatly exaggerated. Let’s move beyond the numbers, though, and talk about the actual experience.

Yeah, wait. Didn’t You Say This Was An Article About, Like, Your Work Day?

Ok, I’m getting there. How do I factor into this?

Well, having fully given up on my career aspirations of being a member of the technocratic elite and working in an ivory tower to design and dispense structurally innovative policy and business solutions to equitably solve the world’s problems around climate change and sustainable city planning, I now have what most people might call an extremely boring, basically blue-collar job. Based on a presentation to my team yesterday, however, I might actually call it “light blue collar.” Or, bluish-white. What’s the difference? It’s like that dress where you can’t decide whether it’s black and blue or gold and who the hell even cares (but– side note- the dress thing actually has a kinda interesting backstory).

Anyway, I manage a team of energy efficiency installers for a public utility demand side management company. I have a neat little office. I produce simple, legible spreadsheets, track simple performance metrics, and attempt to orchestrate some semblance of order in a neverending, complex, and muddled series of intertwining workstreams. I sometimes interact with human beings in the utility world and talk about Business. And, once in a blue moon, I have to talk about energy policy in a public setting.

But yesterday, I had to venture out to the east side of Detroit in an industrial wasteland of an area that I might name the Body Dumping District– a strange, industrial stretch of land between Mt. Elliott St. and, well… it’s not really clear from looking at the map. It’s a mini-industrial district sandwiched between super low density residential neighborhoods and a rail corridor. If you were stuck in the middle of it, you might think it went on for longer than it really does, because the urban density is just, well, that low. Doesn’t even really feel like the city at that point.

The Search For The Perfect Plumbing Fitting

I was searching for two things: the first was a basic reducer bushing. It’s a galvanized steel pipe that can be found at almost any hardware store, and it will enable Sean, one of my star installers, to install several hundred water-saving showerheads. The other part was a specialized faucet aerator adapter that is used on a certain type of sink– either certain kitchen handwashing sinks, or, oddly specifically, the sinks that are used in school chemistry labs. Amazon stocks these. Home Depot does, too. But they’re more expensive. (At Home Depot, this, we suspect, is the tradeoff of them being neatly, individually packaged with their own bar code that even a robot can figure out how to scan).

I had to remind my team– who are not plumbers- that we cannot buy black pipe and must instead buy galvanized iron, stainless steel, or brass. Black pipe is not suitable for water piping for two reasons, the most important of which is that it will corrode if used with water. The second reason is less significant, and that’s that black pipe is usually covered with some remnant of that yucky cutting fluid. You don’t want it near your water supply. When I was doing construction full-time, one of these parts cost several dollars (brass) versus $2-3 for galvanized iron or black pipe from a big box store.

Metal prices fluctuate wildly and globally. I recall having paid as much as $6-8 for one of these fittings. Yesterday, I found galvanized fittings for $1.50 each. This was also the same price to have them shipped to me in two days from Amazon– in yellow brass, no less, while, just a few years ago, those were double the price. While Amazon is able to quickly respond, it’s also shipping a lot of stuff from China. Global fluctuations in prices complicate this calculation on either side of the Pacific.

Fortunately, Sean had tracked down this business. They did not have a functional website, nor an online ordering portal. But they did have stock! So, off I went.

So, Why An Independent Business?

It goes without saying that shopping at most box stores is often enough to make you question not only whether capitalism is a virtuous system, but whether or not you want to continue to live on the planet at all. It’s hard to find help. The people you do find are likely to have absolutely no training in whatever they’re tasked with selling. Even though it’s not really about the humans doing the sales, though, is it? Nay, good reader, it’s about the prices! At their best, stores are well-organized an affordable and well-stocked. At their worst, well, you’re stuck with lousy customer service and limited availability. Detroit has exactly one big box retailer in the city limits, and it is, unfortunately, one of the pro-fascist ones.

One other element that brings people to places like Home Depot instead of Federal Pipe & Supply Company is the fact that Big Box Retail– and even many mom-and-pops, for example- is, generally, clean, well-lit, and at least vaguely organized. Federal Pipe is one of those places that will eventually be demolished and designated a Superfund site. Pipe cutting is a dirty, thankless task, and certainly among the least glamorous of any trade. The use of a pipe threading machine, for example, which is required to machine pipes (“nipple”, as it is called, because of how the ends taper so they can thread into another part), requires a constant supply of cutting oil. There are metal shavings everywhere, which might slice open a finger, or they might fall onto the floor, staining the concrete as they mix with whatever most foul mixture of stanky hydrocarbons constitutes the cutting oil. (I just found out while writing this that some cutting oils still, to this day, contain added lard— I kid you not). This is what is probably inevitably embedded in the contaminated soil of any facility that is processing pipe at scale.

I mention this for the purpose of illustration, but also because it highlights how it’s physically a dirty process from a retail standpoint. Amazon is a few easy clicks. Coming into a physical location and getting a carbon copy of my receipt printed by some ancient dot matrix printer is somewhat messier. I’m meanwhile wondering what that funny-colored smoke is coming out of the smokestack across the street, kind of a thing.

But ultimately, it was far faster. The closest distribution hubs couldn’t get me my brass parts faster than two days. I found galvanized parts locally within an hour.

So, The Real Takeaway From This Article Is That Iron Pipe Isn’t Vegan?

It may not be! Certainly, if it’s cut with Hercules Brand Extra-Dank Sulfur Lard Base Cutting Oil. (With the exception of “Extra Dank,” the rest of that is entirely real). But remember that whole thing about the complete lack of service from a Big Box store? They’re definitely not going to be able to tell you what’s in that cutting oil. They’re also unlikely to have an office mascot dog named Owsley Stanley but who goes by Bear, like the real-life Owsley Stanley, a pioneer of innovative sound production techniques (and huge proponent of psychedelic drugs in the 1960s).

Looking Forward: Patronizing Independents In The Age Of Interweb

Normally, at work, I don’t deign to leave my lair. To order things from Grainger, I fill out a form and submit it to an internal e-mail address, and I receive it in a few days, usually. Amazon? I fill out the same form and wait 4-6 weeks to receive my package. Different vendors operate differently for our company. But I am often on the hunt for new vendors. Better prices are always great, but better service is also great. Grainger, for example, has terrible service and terrible prices. They’re the preferred vendor for a lot of things because, well, first mover advantage, I guess. While many stores offer volume discounts, Grainger has just dived headfirst into the deep end of price discrimination.

Generally, in any established business, there’s a level of comfort that often verges on complacency around existing structures. Why would we ever want to change things? In the cases where we have vendors we’ve used for years, well, we have relationships with them, right? Why should they ever have to adapt?

I’m a millennial, people! I have seen a number of important economic institutions and systems blown up and rebuilt in my own lifetime. I’ve also seen this happen with systems I was told to put all of my faith and money into. I’m thinking about everything ranging from college education to the mortgage market to cryptocurrency. Ergo, I’m interested in challenging bad systems. If that means breaking it off with Grainger, great. If Leon and Debbie at Federal Pipe aren’t sufficiently responsive to be able to get me a decently priced supply of stock, then we’ll probably have to avoid using them in the future, too.

But there’s a whole thing here. I’d much rather be able to schedule virtually instantaneous pickup– within, say, ten minutes or half an hour- rather than go through seventeen layers of distribution, profit margin, and organizational dysfunction that is involved with an Amazon or Grainger delivery. Amazon is mostly a distribution and logistics company, and it sells third party products for which the offered warranties and customer service are often nonexistent. It will often tell you one delivery time and give you another. Grainger, the other day, just shipped me 500 faucet aerators in 17 different packages. Why? Because they didn’t have them all in stock. One package– I kid you not- was a single aerator inside a package the size of a cereal box. It cost probably $10 to ship that $1 item. Okay, Grainger. Carry on, I guess?

A small business doesn’t necessarily have the sophistication to develop from scratch some sophisticated inventory system. Nor should they be required to cater to the whims of impatient, individual customers– inured to the fast pace of global e-commerce- buying in tiny quantities to survive. But there are plenty of platforms that allow relatively seamless integration of card processing and what not.

For Small Business: How To Compete?

Good customer service means something different to everyone. For me, it means making my life easier as a customer. It doesn’t simply mean “finding the best price.” Federal delivered for me, but they also fell short in a few regards:

- Asking the customer to send credit card information over e-mail in a PDF form. This is just a frankly premodern thing. Anyone who knows anything about data security knows that this is a cardinal no-no. Of course, they took my card through a modern card reader. But they also had a carbon copy credit card imprinter. These were, to my knowledge, invented in the 1960s or so. There is no reason why business owners should even hold onto old technology like that unless it’s in a display case.

- Not having an online payment portal. These are, quite literally, free to set up. Sure, you have to pay credit card processing fees. But you have to pay those anyway!

Leon, from Federal, told me that for him, it didn’t even make sense to do much in the way of cash-and-carry sales anymore. Most of their business is with large commercial and industrial clients. There’s not much business sense in spending an hour helping a customer track down a $2 fitting. This is the age-old challenge of the mom-and-pop. Of course, there is customer service sense in doing it, and the people who help customers solve tiny, unglamorous problems do it because that’s part of how good service works. But, absent a huge resulting spike in sales, it doesn’t make financial sense.

Some things that these companies could easily do:

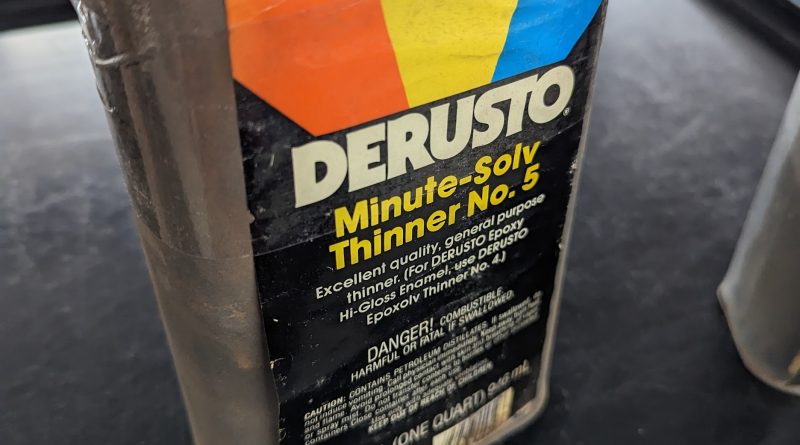

- Clear out old merchandise and stock things that people want. It’s one thing to sell “new old stock” from the past three years. It’s another to have a can of Derusto on the shelf that is itself so rusty that, well, let’s be real, no one is ever going to buy that. Same is true with the ancient sinks on display. That’s valuable floor space. In a market with higher demand for real estate, that’d not only represent a poor allocation of space, but also opportunity cost. Inventory is, of course, expensive. But that’s why a lot of mom-and-pop stores opt to partner with various other retailers or smaller companies, selling on consignment, or even sub-leasing space for sales of specific products.

- Creating a modernized inventory management platform that integrates with various secure payment portals, payment processing, and delivery systems. The sky is the limit on this front– there are options that might cost you only a few dollars per month, and then there are options that might cost you hundreds of thousands.

- Being responsive to customers. Some customers prefer the telephone. More customers nowadays prefer alternatives, whether e-mail, text, or chat (from a web application). Again, these things often can be API-integrated into other platforms, quite affordably. It also requires staffing of such a system. In 2023, it’s impossible to have a single computer monitor and run a whole business off it.

But further, the problem is that, absent some sort of strong, inevitably impossible-to-construct, federal plumbing standards, we can’t really fix this problem of the one-hour-for-a-$2-part issue. What we can fix, however, is figuring out how to humanize increasingly faceless retail transactions. Will Federal Pipe & Supply be the place to make that happen?

Based on my experience yesterday, maybe not. Its owners are at or nearing retirement age anyway, and are probably not doing this to get rich at this point. A lot of mom-and-pops are subjected to ego risk– everything risks falling apart if one person doesn’t show up to work for a day, a week, or ever again. This has been extensively observed with Elon Musk, who continues to prove himself unable to manage both Tesla and Twitter as he points both toward financial ruin in pursuit of personal ego aggrandizement (“ego” in Musk’s case referring both to “megalomaniacal tendencies” as well as “the risk of the ownership by and reliance upon a single person”).

Transferring a business to a new generation is another option, and there are hopes that this could translate to modernization of the business. Ozy’s Joe Hasler observed this same thing in exploring some solutions that were being explored a few years ago to stabilize the independent hardware store:

“…the North American Retail Hardware Association has launched several initiatives. These include connecting mentor-owners with would-be shopkeepers and partnering with Ball State University, in Indiana, to create a six-month, college-level certification course that features in-store training and lessons on strategic business planning and retail financing. Tratensek adds: “All of this targets the question: How do we make sure the next generation can take over and run these businesses?”

There’s certainly an interest in intergenerational continuity. Heck, I’d love to run a hardware store. I don’t know that I’d be great at it, but I think I’d be good enough at it. “Good enough plus volume plus specialization” is a formula that has worked for many businesses trying to compete in any era of American consumer economy. While some independent hardware stores are still delivering excellence on a consistent basis, the quick delivery and lower price points alone of the giant stores aren’t necessarily going to be enough to translate to some sort of triumph on their part.

Businesses are fundamentally situated in community. The numbers show us that these smaller businesses aren’t necessarily flourishing. But they do show us that they’re hanging on. And for my part, I’ll continue to push both big business to do better as far as service quality– and small business to innovate to compete.