How To Find Nonpartisan Consensus in Sustainable Urbanism

I was recently in Southwest Florida for the first time, checking out damage from Hurricane Ian and exploring the region. I had previously been to Tampa, Miami, and Orlando, (and once, as a tiny child, to the Panhandle). Southwest Florida is a completely different world altogether, and I was glad to get a different perspective on the Sunshine State. So, last night, I met up with an old friend from Michigan, Andy Wells-Bean, a longtime Handbuilt reader. A Michigan native, Andy now lives in Naples with his wife and two young children. He has a nine-to-five working for a church, and his wife is a minister. Unlike the gaggles of retirees, they did not move down here for the weather, but rather for work– and for better options than they found in Michigan.

I asked him pointedly: If you’re a person of a specific political affiliation living in an area where your values are completely at odds with the dominant ones of the area, how do you manage? How do you engage with your community? More specifically, how can you work with folks you might not agree with to achieve a common goal? Is there a way we can achieve consensus of any kind in this age of what feels like, well, pretty broad, complete collapse of The Discourse? And everything else?

For my purposes– and Andy’s, too, since he’s interested in much of the same stuff as I am- how can we talk about sustainable urbanism in a way that can build consensus with folks we might not agree with on paper about much? In an age when people will scream that we’re being communists for proposing that cities have adequate transportation infrastructure, what’s one to actually do to avoid feeling like we’re just banging our heads against the wall?

Andy sees some possibilities in Southwest Florida.

Humanizing a Less-Than-Humane Built Environment

We are pondering this question while dining at Oak & Stone, a well-trafficked restaurant in, dare I say, a more elegant strip mall, about 13 miles northeast of downtown Naples. Three of us are sitting on the patio, screened from an expansive fountain that separates us from the intersection of two stroads, Logan Blvd. and Immokalee Rd. Traffic zips past in either direction, save for the periodic, inexplicable traffic jam. These are common in the region, which has experienced explosive growth in the past decade as the state government has eliminated growth management oversight (more on this in an upcoming article).

We enjoy appetizers of fried pickles and Philly cheese steak egg rolls. I also visit the “beer wall,” which features dozens of varieties of beers, mostly IPAs and yellow beers that require you to swipe an RFID wristband. We can live in the technological future while living in the sociopolitical past! As I’m waiting at the front, a gaggle of nearly-identical, potbellied, golf-shirted men in their 60s and 70s waddle in, the keys to their [Mercedes/Giant American SUVs/BMWs/Excessively Large Luxury Cars] jingling in hand. A somewhat cross-eyed elderly gentleman at the next table has a fire truck red shirt on that features a Thin Blue Line flag shirt with Matthew 5:9 printed on it in block letters.

While waiting for our food, we watch a child walk out with his parents, and he’s dressed in a costume tactical vest with a toy gun, swinging it around as they stroll along the sidewalk to their car. Cosplaying just in time for Halloween!

“Oh my God, is that kid dressed as a terrorist?” my Canadian co-conspirator asks. God bless America. It sure looked like it.

Suffice it to say, it’s not the kind of place I typically hang out in.

Traffic engineers, in their quest for improving level-of-service, will figure that an eight-lane road might help. Once that road is clogged, they figure out ways to justify adding more lanes. “Just one more lane, bro!” We know that this is both ineffective and a massive burden to taxpayers, not to mention commuters who have to deal with the new traffic.

Enter The Bike Grid

Andy thinks that there is opportunity in thinking about how to build safer infrastructure by way of what we nerdy urbanist people call a Bike Grid. This means that instead of just adding bike lanes on stroads as an afterthought– especially in the form of painted bike lanes or, God forbid, sharrows– that there would be a dedicated network of dedicated cycling infrastructure. After all, we have dedicated infrastructure for other things, right? Roads, rails, drinking water, stormwater, sewage, and power lines. Why not for sidewalks and bikes? Road engineers usually approach this as a matter of checking a box and believing that humans will all behave rationally and safely. “We painted a bike lane! What more do you want?!”

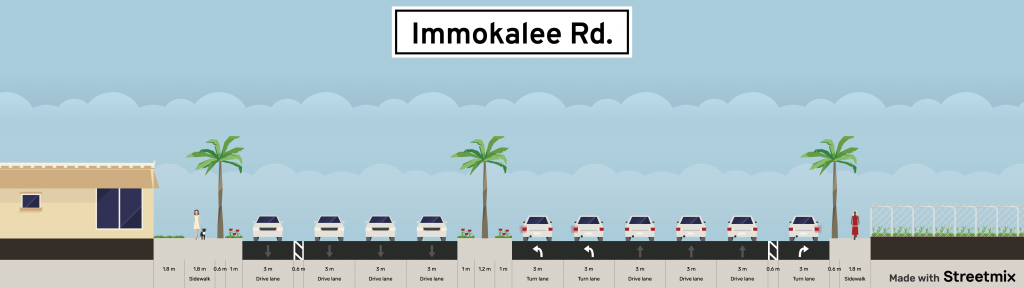

Infrastructure, generally, should hardly be an outrageous proposition. But beyond that, it’s something that Andy thinks would be relatively easy given a common typology we see in the built environment in these parts of the world. Let’s have a look at the typology of the road we’re on:

Andy starts by pointing out the ubiquity of ultra-wide streets (usually six to eight lanes for arterials) and the ubiquitous stormwater management infrastructure in the region. Huge public rights-of-way are a good opportunity for thinking about better infrastructure, because they represent a great deal of inefficiency through a pretty much endless expansion of lane miles. Traffic engineers, in their quest for improving level-of-service, will figure that an eight-lane road might help. Once that road is clogged, they figure out ways to justify adding more lanes. “Just one more lane, bro!” We know that this is both ineffective and a massive burden to taxpayers, not to mention commuters who have to deal with the new traffic.

Consensus Point 1: “People Dying Is Bad“

Florida leads the country in cycling fatalities. (“U-S-A! U-S-A!”) This isn’t a good thing in which to be Number One. Ask any motorist, and they’ll likely tell you that, well, it’s the cyclists’ fault! “I saw one roll though a red light one time!” Or, “They should be on the sidewalk!” Of course, in virtually any jurisdiction in the United States, cyclists are legally entitled to the same treatment as vehicles and are usually allowed to take the full lane, as a car would. Cyclists are often not allowed to ride on sidewalks. Or, if they are, it’s not really safe to– because sidewalks are meant for people who are walking (or in wheelchairs or strollers, for that matter).

As a brief sidebar here, the idea that cars and cyclists can share the road and that cyclists should operate as cars is sometimes called “vehicular cycling.” There is a lively debate in the cycling community that argues that this was never a good model to begin with. Bicycles should have their own dedicated infrastructure, many advocates argue. If I’m weighing in, I don’t think that it’s impossible to have safe, vehicular cycling. I’d prefer separated infrastructure. But that’s not pragmatic for 100% of the lane miles, corridors, or roadways we have.

Plus, there are plenty of new technologies that are already proven to have a substantial benefit in safety– things like automatic braking and collision avoidance, lane-keeping assist, and more. However, barring some aggressive legislation and expensive federal programs, it’s going to take another couple of decades until these are universal. These also are treatments and are neither cures nor preventive measures. There is no broad discussion about the idea of speed limiters, which transportation safety advocates point out would probably save a lot of lives– not to mention fuel!

In conclusion? We should all agree that we want to reduce the rates of cycling, pedestrian, and automotive fatalities. Cars kill more than a hundred Americans every day. Safer infrastructure for cycling will translate to safer infrastructure for everyone. That’s not really a point that anyone can specifically argue with. This brings us to our next point, and that’s the environment in which we have to pitch this kind of idea.

Consensus Point 2: “Tourism Dollars Are Good“

Florida’s economy is defined principally by two things: tourism, and as a destination for northerners fleeing the cold– and retirees. It’s sort of hard to entirely separate the two, because the state has thousands of communities occupied by a mixture of snowbirds and permanent resident retirees. While there is unlikely to be any sum of money I’d take to live in DeSantis Palms, or whatever the “community” is I’m living in this week, plenty of people love it. The 90-degree heat in late October is jarring to my Yankee brain. However, I can see why people like an arrangement in which nearly every day (in certain seasons, and with the exception of destructive hurricanes) is beautiful! We, too, heard the rainstorms ain’t nothin’ to mess with, but we can’t feel a drip on the strip. It’s a trip. But I digress.

This economy means that Florida’s public sector should focus on making the state attractive for tourism (or retirees!). The two can go hand in hand, because young people and old people both love to ride bikes! Anecdotally, I’ve probably seen more old people riding bikes this week than I have ever seen in Southwest Detroit. Of course, older cyclists are generally physiologically less resilient than young cyclists, which makes an even stronger case for protecting their safety by way of better infrastructure.

Concluding the second point here, the public sector should make sure that environments are hospitable to tourism and people who like to explore and come visit.

Conclusion: Infrastructure That Improves Tourism And Safety Is Good

The role of the State isn’t just to build and maintain infrastructure. It’s also to figure out ways to promote responsible behavior and discourage irresponsible behavior. While I disagree, for example, that the state should be promoting Christian values by installing the Ten Commandments in front of a courthouse, I definitely think that there are opportunities for the state to encourage, broadly, moral and ethical behavior! “Don’t murder your neighbor” seems like it might go along with the Ten Commandments as well as with the idea of having safer transportation infrastructure.

I saw some examples of this. Interestingly, the sheriff vehicles in Collier County have a sticker on the back reminding drivers that state law requires you to give cyclists three feet of passing space. This isn’t much of a strong statement, seeing as cop cars routinely and flagrantly violate traffic laws (without sirens or flashers on). And most cycling advocates think that three feet isn’t a good enough distance. (I think 3 feet is fine for lower-speed passing, but low-speed isn’t a thing in Southwest Florida). The point, however, is that such signage communicates information to drivers. If police begin enforcing traffic laws more aggressively– in ways that discourage speeding, for example- this might be a better step. Signage is just one step. It’s admittedly a minor one.

A more major one would be figuring out a combination of infrastructure improvements, policy measures, enforcement mechanisms, and public efforts to educate and encourage better behavior.

Okay, so, the same as everywhere else?

An obvious question might be to ask why this can’t be readily applied to any community in the United States. Contrasting Florida with Michigan, for example? Michigan’s wider roads and rights-of-way, whether in the suburbs or in cities like Detroit or Grand Rapids, might offer some of the same opportunities for considering the expansion of a bike grid. The city of Naples, meanwhile, boasts that it has 30 miles of bike “pathways” within the 14 square miles of its municipal boundaries. Spatially optimized, this works out to bike pathways at a 1-mile interval grid.

But that the city’s actual streets feel pretty hostile to bike safety suggests that a 1-mile grid is probably not how the bike paths are actually set up, and, further, that most of these “pathways” are probably not dedicated or protected bike lanes, but rather just painted ones. Naples’ major north-south thoroughfare Tamiami Trail, for example, has but six travel lanes (for cars) and sidewalks. There really isn’t, at present, any good north-south dedicated bike route in or out of Naples. This can be referenced on the city’s bike map. Again, more on this soon in another article!

Things To Look Forward To

But there may be a dedicated route some day. The Naples Pathways Coalition is advocating for a major infrastructure project, called the Paradise Coast Trail (I’m thinking “Sprawl Coast Trail” might be a more appropriate name?), while also pushing for other policy measures, like making “no texting while driving” a major law enforcement priority (which, they note, it is not at present).

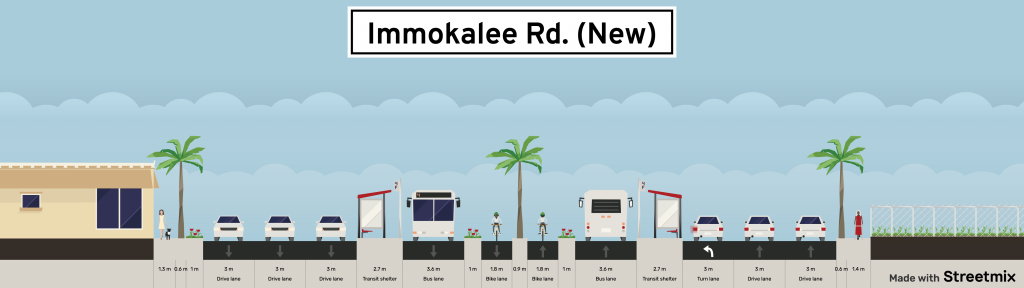

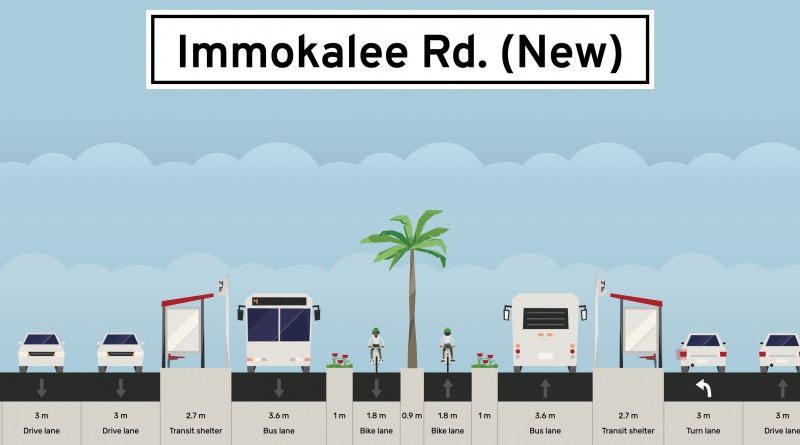

In the meantime, check out our proposal for the new Immokalee Road outside Naples. We’ve reduced the number of travel lanes to four principal car lanes, a dedicated transit lane in either direction (which might well be able to reduce to one single lane, since buses can be coordinated like that!), plus bike lanes and sidewalks on either side. The major difference? Eliminating the double turning lanes plus the single or double left-turning lanes.

If traffic gets any rougher than it is now, well, maybe it’s possible to consider an alternative way to get around! After all, it seems like that’d be great for public safety and the region’s large number of tourists!