Losing Your Shirt: Amazon’s Anticompetitive Edge in Pricing

I conducted a bit of an experiment from last year into this year involving everybody’s favorite online retail giant. This began as part of a somewhat passive compulsion that I found myself drifting into during the depths of lockdown, involving a somewhat obsessive process of comparison shopping to try and understand how companies like Amazon manage pricing. I called this “electronic window shopping.” I came up with some interesting conclusions. Amazon makes millions of price adjustments per day. Amazon’s ostensible rationale for its pricing is that it wants to be competitive with like products from other companies. Generally, this seems to make sense. But there’s something else going on, which I’m going to try and unpack.

Undercutting The Competition

It’s probably the worst-kept secret in the business realm that Amazon doesn’t actually make money off its retail business. But the retail is the cash cow, even if it’s not the profit cow. Amazon Web Services comprises most of the company’s actual profit. The company is so big that AWS and Amazon retail operate, well, almost as separate companies and largely do completely unrelated things. This is one of the big drivers behind the push for antitrust litigation. At this point, Amazon retail likely couldn’t exist without AWS. And AWS wouldn’t exist without the ability of the retail business to create such massive economies of scale for distribution, logistics, and purchasing power. (I have a hunch that there’s some shady business going on as far as Amazon’s retail business buying services from AWS and AWS accordingly profiting as far as transfer pricing).

A Normal Enough Example

Let’s say Best Buy sells a pair of headphones for $20. Amazon sells the same pair for $19.87 including Prime shipping. There’s the added bonus that you don’t have to sit in traffic and drive to some godawful, TIF-funded strip mall to buy the damn thing. Assuming both stores have the same purchasing price and volume, Amazon’s selling it at this lower price so it can undercut Best Buy. Monopolists try to eliminate the competition so they can then drive up prices with a captive market.

Average markups vary by industry. They’re usually very low– 5-15%- for durable goods like cars. Clothing usually has a sky-high markup, like 100% or more. Electronics might vary, but let’s say that these headphones have a markup of 30%. Amazon’s margin would be around $5.96, while Best Buy would be earning $6. But Best Buy has no marginal cost of delivering the thing because it’s already on the shelves. Amazon’s marginal delivery cost might be $2-5 to get it from the warehouse to your house. At this point, it has made as much as $4.96 or as little as $1.96. This is a “normal enough” example.

Store Brands and Loss Leaders

Where it gets complicated is when Amazon is selling its own products. This is a common thing in retail, especially in things like grocery. In my native Southeastern Pennsylvania, I grew up with the Giant stores generic brand Finast, which had a thoroughly unfashionable logo of red, black, and white that looked as though it had probably been the same since its 1970’s conception. Besides the common joke about something being fine-assed, I remember that, while we’d often buy the generic brand for a lot of products, there were some that we would always buy the “real” brand of because the store brand was for some reason shittier.

Consumers often like at least having the option of cheaper products. Retailers often price the generic brands at slim margins to attract customers– same as the idea of the Costco chicken, which sells at a loss. This is called a “loss leader” and there’s a lot of evidence that these products create way more in sales of other stuff than they lose on their own.

The Math of the Store Brand

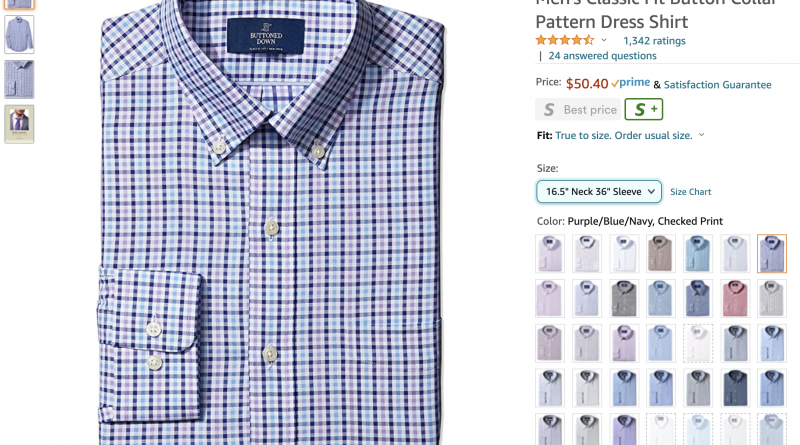

In some cases, the generic brand might even be made by the same factory as the “real” thing. And, indeed, if a company’s store brand is trying to exactly copy the “real” brand, it is still probably going to discount the price. Amazon’s example of the “Buttoned Down” house brand dress shirts retail for around $49.99 normally. But “normally” is a vague term here.

- At $49.99, the shirt is expensive and possibly unaffordable to the average buyer. Amazon clears a substantial profit. This is the “default” price.

- At $39.99, the shirt is pricey, but more doable, especially if the consumer is familiar with the brand. Amazon is still clearing a tidy profit on the shirt.

- At $24.99, Amazon’s clearing some profit and the product become smore

- At $14.99, the shirt is a deal. But at this point, Amazon is probably actually posting a minimal loss. I considered this from comparing hundreds of data points from shirts offered for sale on Ebay, AliExpress, and Amazon. On Amazon, third party sellers aren’t selling button-down men’s shirts for much less than $20 or $25. Ebay averaged at $22.12 (after eliminating a few giant outliers– Canali and whatever). Ali Express was a pain in the ass to analyze but the prices were substantially lower (and, according to a number of Reddit commentaries I’ve read, so, too, are margins).

- At $4.99, the shirt is unequivocally losing Amazon at least a few dollars per sale.

- At $2.90 (the lowest price I found), the shirt doesn’t even cover the shipping cost, let alone the production cost. I figure Amazon is probably losing $5-11 per transaction at this point.

My Own Math

I analyzed a list of 207 products I found, all priced differently and selected based on lowest possible price within that product category. These were all Amazon brand products and most were men’s shirts. The average sale price was $8.60. Many of these purchases would have qualified for a $1-2 “no-rush shipping” digital credit, which I figure gives Amazon a net of at least 50%. So, at an average procurement (purchasing from supplier) cost to Amazon of $7.33 and an average shipping cost of $2.57, Amazon is losing an average of $0.87 per sale on these products. Change the sale price up to $49, though, and they’re making a princely sum per transaction.

What’s Amazon Playing At?

Circa ten years ago, I found myself predicting that Amazon was going to eventually become so good at selling, that it’d inevitably just become a logistics company rather than a retailer. This seems to be increasingly accurate. The company is deploying increasingly sophisticated systems to get people the shit they don’t need but inevitably order– faster and more accurately. The system automatically sorts things based on a variety of criteria, and the result is that you can get virtually anything delivered, well, often on the same day at this point.

As for the shirts? My theory is that Amazon is using its rapid-fire pricing adjustments to normalize sales volume. If you aren’t selling shirts at $49.99, maybe you’ll sell them for $40. If they don’t sell at that price, try $30. And so on. They might also be trying to normalize sales revenue, but in this case, volume is a bigger deal because of the logistics-heavy nature of eCommerce.

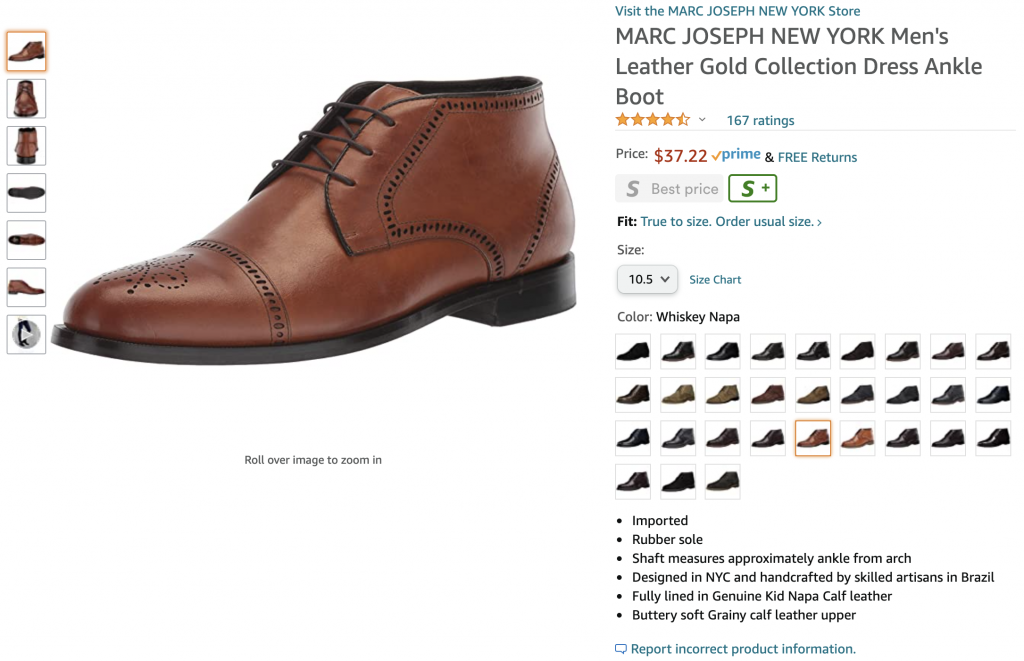

If you want to help Jeff Bezos lose money on a marginal basis, you can find some really good deals on men’s shirts. Or splurge on some all-leather dressy boots.