COVID, Bad Data, And The Rural-Urban Media Divide

In recent weeks, a lot of Americans in major metro areas have looked at the daily COVID case counts around the United States and wondered: “where is this happening? It isn’t happening here.” So much is, well, true. Cities that got hit hard by the novel coronavirus in the spring of 2020 have thus far avoided an explosive growth rate in the fall wave. During that time, the narrative was exactly the opposite. “It’s not happening in our small town, so why should we care?” A Princeton study published earlier this year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences seeks to explain this along a key question of the rural-urban media divide.

Seeing The Local

This problem is partially geospatial. When I leave my house to walk the dogs, I see my neighbors, the Joy Road Bus, perhaps a garbage truck. As Detroit was hit hard early on, the city adopted aggressive measures to combat the spread of the virus. So, we don’t see as much of it in our immediate neighborhood, even though aggregated state numbers tell a very different story. Thus, the problem is substantially informational in nature. For the most part, it’s easy enough to find data about infection rates outside of cities. But the fall wave– second wave, third wave, whatever you want to call it- highlights a big problem in American society, and that’s that people in cities have access to completely different information than people in rural areas. Nowhere is this more apparent than coverage of COVID. In an era in which Americans consume more and more media but from increasingly limited sources, It’s entirely possible that this information gap has indeed exacerbated the pandemic. The study observed:

Leveraging quasi-random geographic variation in media markets for 771 matched rural counties, we show that rural residents are more likely to practice social distancing if they live in a media market that is more impacted by COVID-19. Individual-level survey responses from residents of these counties confirm county-level behavioral differences and help attribute the differences we identify to differences in local television news coverage—self-reported differences only exist among respondents who prefer watching local news, and there are no differences in media usage or consumption across media markets. [emphasis added]

CovidActNow estimates the ICU “headroom” capacity of every state and compares infection rate, new case rate, positive test rate, and contact tracing rate. They call the ICU capacity function a “beta” version, and so it’s not necessarily 100% accurate from day to day. In order to drill down into more accurate numbers, I started looking at local news outlets in COVID-heavy western states. In Montana, the Dakotas, Oklahoma, and Idaho, I compared state public health resources to local TV stations and newspapers. Disparities abounded– less in the reporting than in how easy it was to get access to the information. For example: KELOLand, a Sioux Falls, South Dakota news station and subsidiary of a larger media conglomerate, has a respectable set of infographics. North Dakota has a clunky, though fairly comprehensive state dashboard. One smaller media outlet I looked at from South Dakota, however, claimed that they had only been able to obtain accurate information about COVID19 from the state after a contentious FOIA request.

Where The Data Live

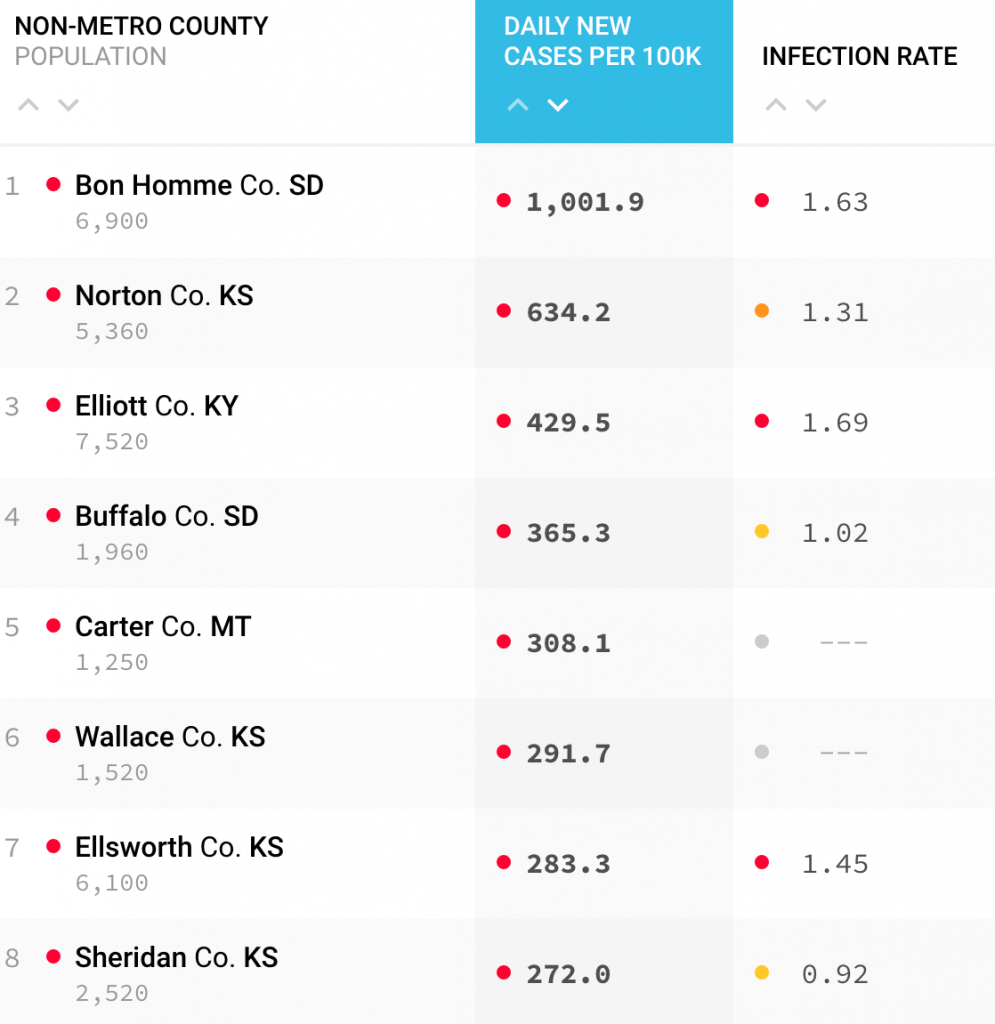

States and hospitals all submit their data slightly differently, which accounts for things like the zig-zaggy daily case counts apparent on pretty much any state’s graph. It’s easy enough to look at case counts when they’re aggregated on one of the big websites. Johns Hopkins provides comprehensive resources. The CDC, which the (thankfully departing) Trump Administration has continually undermined in an attempt to downplay the virus, provides reliable resources. The visual table on Worldometer provides a great numerical summary, and independent reviews of this private website have determined that, minor methodological issues aside, it’s generally about accurate. When you want to get into more granular data, though, you might look at something like CovidActNow, a nonprofit resource that lists detailed data by county.

…this issue becomes far worse when we’re talking about a virus that a lot of people simply don’t think is a big deal. It has a 99.6% survival rate, they say, apparently unaware of the intuitive logic– and accompanying arithmetic- that you can’t die of an illness you haven’t contracted.

The Good, The Bad, And The Terrible

In other words: it’s a mixed bag. While there are already major disparities between urban and rural areas in terms of infrastructure and information access, this issue becomes far worse when we’re talking about a virus that a lot of people simply don’t think is a big deal. It has a 99.6% survival rate, they say, apparently unaware of the intuitive logic– and accompanying arithmetic- that you can’t die of an illness you haven’t contracted. Notably, these states are overwhelmingly Republican. United under the banner of President Donald Trump, Republican Party has, across the United States, generally downplayed the threat of the novel coronavirus. Not so, his supporters will say. He took unprecedented early action and shut down travel from China! (Narrator voice: And, as it turned out, he didn’t).

As 2020 has taken– and accordingly smashed- the cake for the year of record gaslighting, something I’ve mentioned before, this he-said-but-he-didn’t-say has become a quotidian occurrence to which we have become inured. But this is why it’s ever more important for small and independent media outlets to cover this information. A small TV station in rural North Dakota isn’t likely to provide hard-hitting investigative journalism as much as it is to report on the fundraiser in the basement of the local Lutheran church. Give the people what they want! Small towns embracing the weird sort of prairie populism don’t want to hear about tyrannical Washington leadership undermining American democracy, right?!

Beyond this cultural gap in media consumption, infrastructure is far more expensive in rural areas– so it’s easier to enjoy the ad revenue from TV spots for Ed Olson Buick GMC on Main Street than it is to send a limited staff of reporters into the field to dig up stuff that will really piss off the Republican constituents who are paying your bills (and shopping at Ed Olson’s Buick GMC). This is the media business angle. This involves us asking why the Billings Gazette mentions COVID19 on a given day but once on its home page when a number of hospitals in the state are already exceeding 100% ICU capacity.

And, as opposed to the business angle?

The human interest angle, in contrast, of course. This is one that asks, “why aren’t we hearing more about the high rate of COVID transmission in prisons?” Looking at CovidActNow, prison outbreaks skew the county transmission rates by huge margins. This isn’t front and center, but numerous news outlets have explored it. The pandemic has wreaked havoc on the extremely limited medical facilities at prisons. And we know even more how serious this is, given that addressing mass incarceration has been one of the only issues to attract bipartisan attention in the past decade.

Less prevalent in front page national news is the dire state of hospitals in western and Midwestern states currently experiencing explosive growth of COVID infections and severe shortages of frontline workers as they themselves or their family members get sick.

COVID vs. Rural America

With conditions deteriorating, we’re starting to see action, but it’s taking a long time. Accordingly, the virus is taking its toll, now on rural and smaller hospital systems that avoided the first wave. And the situation is already dire in many states. North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum announced on November 10th that the state is adopting “crisis” guidelines that would allow asymptomatic, COVID-positive frontline workers to staff COVID-positive patients. Montana, which had several hospitals at 100% capacity as early as a month ago, has been posting rapid increases in numbers. The state’s health department doesn’t always make those data terribly easy to access, but they do have a dashboard that covers a lot of it. Utah’s governor just put a mask mandate in place. Utah, South Dakota, North Dakota, Montana, and Nebraska all effectively are at full hospital capacity.

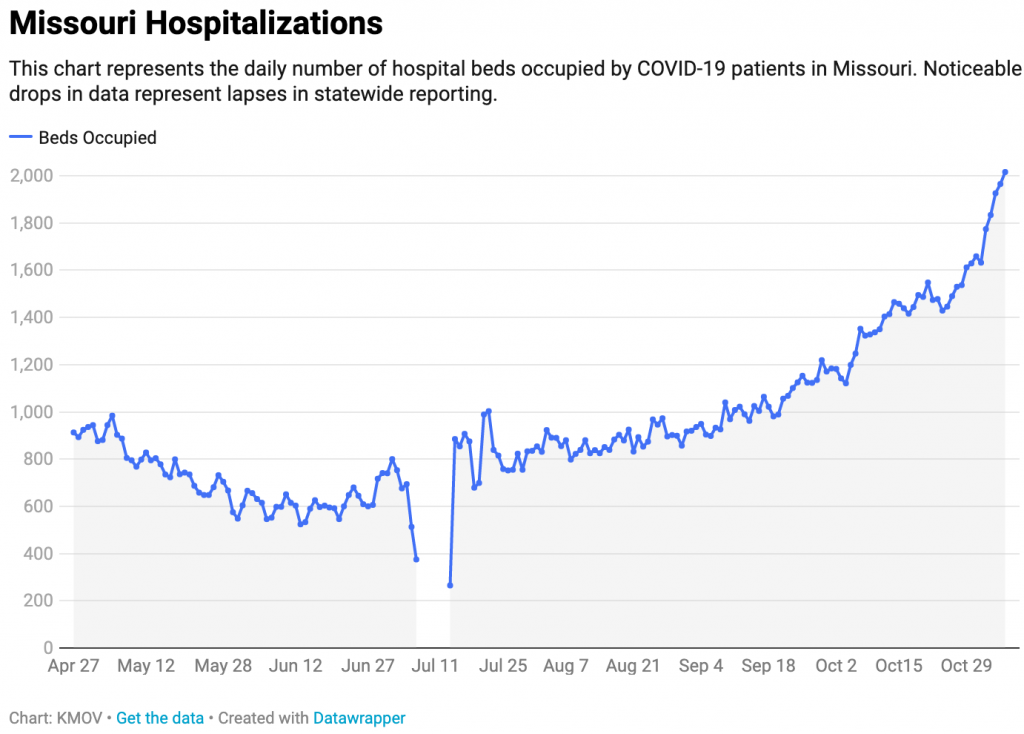

Missouri’s shit is, unsurprisingly, fucked. Beyond the data gap in the graph above, the governor has continually downplayed the threat of the virus. He continues to claim that the state has a huge excess hospital capacity– even though that, well, isn’t really true. Bad data converge with the media disparities identified in our Princeton study. And this is added onto another layer that concerns about the virus are actually indeed strongly entrenched along partisan lines. Fox News viewers, in fact, are more likely to contract COVID; the network came under fire for major pundits like Sean Hannity downplaying it as late as mid-March, calling it a “hoax.”

Compound the challenges of rural data accessibility, underdeveloped infrastructure, the geospatial parameters of rural media markets, and sprinkle some additional partisanship on top, and we’ve indeed got ourselves a bit of a mess. It’s my hope that providing an angle to look at this can help us fill in some of the missing pieces by providing an accurate, responsible media angle. In the meantime, mask up, keep your eyes on the data, and make sure your local elected leadership is doing their part.

Thanks to Dr. Chelsea Shover, an epidemiologist currently doing a postdoc at Stanford University, for speaking with us.