Clever Crowdfunding: Risk, Regulation, and Social Capital

The crowdfunding movement raises many questions about how to protect investors from fraud or risk. A recent article on CrowdClan discusses the debate between “self-attestation” by investors, that is, a fairly typical process wherein investors declare information about themselves and their access to an investment offering is limited or granted based on that information, and the creation of a federal or third-party database that could track and verify all of this information.

Wait a minute. The JOBS Act was supposed to help democratize the process of investment in startups by opening up equity investment to more people, right? After all, the OMB figures that the average SEC Regulation A offering requires more than 600 hours of love. That’s a little bit more than even the sexiest of Kickstarter campaigns. Devin Thorpe’s recent article claims that crowdfunding is becoming a thing suddenly as evidenced by the law’s apparent radical inclusiveness to smaller, wait– accredited- investors. Sure, it does simplify the process of securitization of a startup. Never mind that the average Kickstarter user doesn’t know what securitization means, nor do they know how complicated it is to become an accredited investor.

Indulge me as I hop up on my locally reclaimed wood soapbox for a minute: Ordinarily I might drop to my knees, clench my outstretched hands, and scream an Ayn Randism toward the Heavens to ask why we can’t just let people be people, but I’ve realized two things from living in Chicago: The first? Most kinds of restrictive regulations don’t work very well to achieve their intended goals. The corollary is the second thing I’ve learned: that restrictive regulation invites clever workarounds, but that innovation is really more a matter of making the right connections and having the right system in place rather than waiting for the government to slowly adopt regulation that won’t end up making much sense anyway.

Around the time I was getting set up on Fundrise, my partners in Indiana told me we should do a Reg-A offering, and the math worked out that we’d raise about a million dollars and pay some six-figure package of fees to lawyers and brokers. Lawyers and brokers I have never met, lawyers and brokers who do not live in my neighborhood or work in the distressed communities that I work in. An offering with the approval of the SEC, but at a six-figure cost?

Nobody has time for that.

What the partnership usually did instead of securitizing anything is instead borrow money from investors and use that money to set up a corporation, whose operating agreement would stipulate that after that money was invested in real estate, the real estate would pay back the investment loan and renovation costs (on a last-in, first-out, or LIFO, basis), after which net cash flow and profits would be split equally between the principal (lender of the original chunk of cash) and the managers. In terms of its legal and fiduciary structure, this was extremely risky, because it was unsecured debt (the debt did not confer any lien positions on the property because of the added legal complexity of doing so), but the capital stack was quite simple because the money went from cash (from the principal) directly into real estate, and the operating agreements outlined the rest.

Theoretically, at least.

The argument in favor of crowdfunding à la Fundrise is that the bypassing of possible restrictive regulations of the JOBS Act doesn’t necessarily result in a riskier product. Case in point: The regulation doesn’t necessarily achieve what it’s supposed to, even if it’s not, in and of itself, a failure, and, make no mistake, investors interested in a project will figure out how to get their capital into the project, regulation or not. The key, then, is figuring out how to mitigate risk.

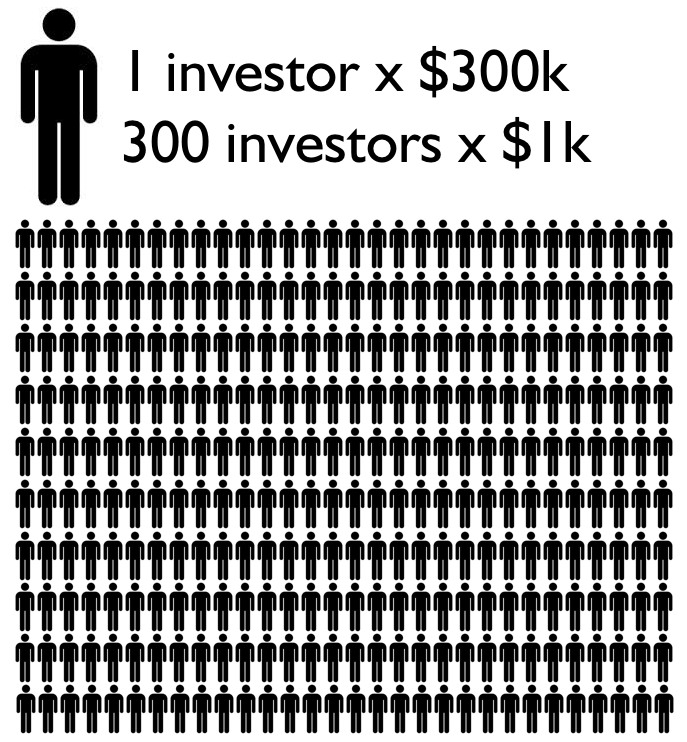

The very point of the writ-large Crowd, like its shifted-consonant counterpart, the Cloud, is that decentralization can (and should) actually be a way to solve problems. Crowdfunding operates on a network of social capital as much as it does on one of financial capital, but the decentralization of capital is as important in mitigating risk as it is in broadening outreach. I often say that Fundrise is more important as a tool for outreach (for me, at least) than it is as a tool for investment fundraising, but in spreading out risk over many investors instead of a small handful of investors, you’re also addressing an important issue, especially when thinking about funding projects that won’t get funded otherwise, say, by banks or large PE investors.

In considering crowdfunding for startups, which are much higher risk than even distressed real estate investment, though bankers might quarrel with my characterization, Dr. Marina Nehme, an Australian law professor, expressed doubt in an article last month in The Age by Mahesh Sharma, that deregulation would do little other than undermine investor protection, market fairness, and transparency, instead driving up risk. “Certain crowdfunding platform providers have dismissed this risk by noting that the ‘wisdom of the crowd’ would help discover potential fraudulent projects,” she said.

This may be true for high-stakes startup ventures, where many companies fail and a very few comprise most of the actual profit being made from such ventures. But real estate is completely unlike startup ventures. Buildings are expensive and used by many people, so crowdfunding can capitalize on that pool of people. Fundrise isn’t producing venture apps with dubious value, it’s producing institutions concretely, pun intended, situated within human communities.

As far as the value of the crowd in determining the viability of individual crowdfunded investments, place not the crowd on any pedestal, for it comprises ordinary, flawed human beings flawed like any other economic system. But increasing the social capital in the process of capital sourcing means that more information will be shared, and more information leads to more transparency. More transparency leads to mitigated risk. I’m not arguing for or against regulation, but I think that we need to push for innovation over regulation, and innovation comes at a structural level such as how we think about the makeup of investment at the levels of its individual investors and their relationships with the principal, with each other, and with their communities.